Et une, deux, trois….quarante minutes d’apnée dans les méandres d’une certaine pop made in France, quelque part entre gauloiseries, fulgurances, et ritournelles aventureuses. Une plongée dans une pop à la Française sans complexe et insolente; une pop Bleu-Blanc-Rouge qui ne se prend pas au sérieux n’en déplaise à ses contemporains Yéyés pas toujours très inspirés. Une pop riche d’une créativité certes pas toujours bien canalisée, avec des arrangements « chelou », des compositions fumantes, et des productions bancales… mais ô combien savoureuse.

WIZZZ 3 c’est la France qui tente, qui expérimente …

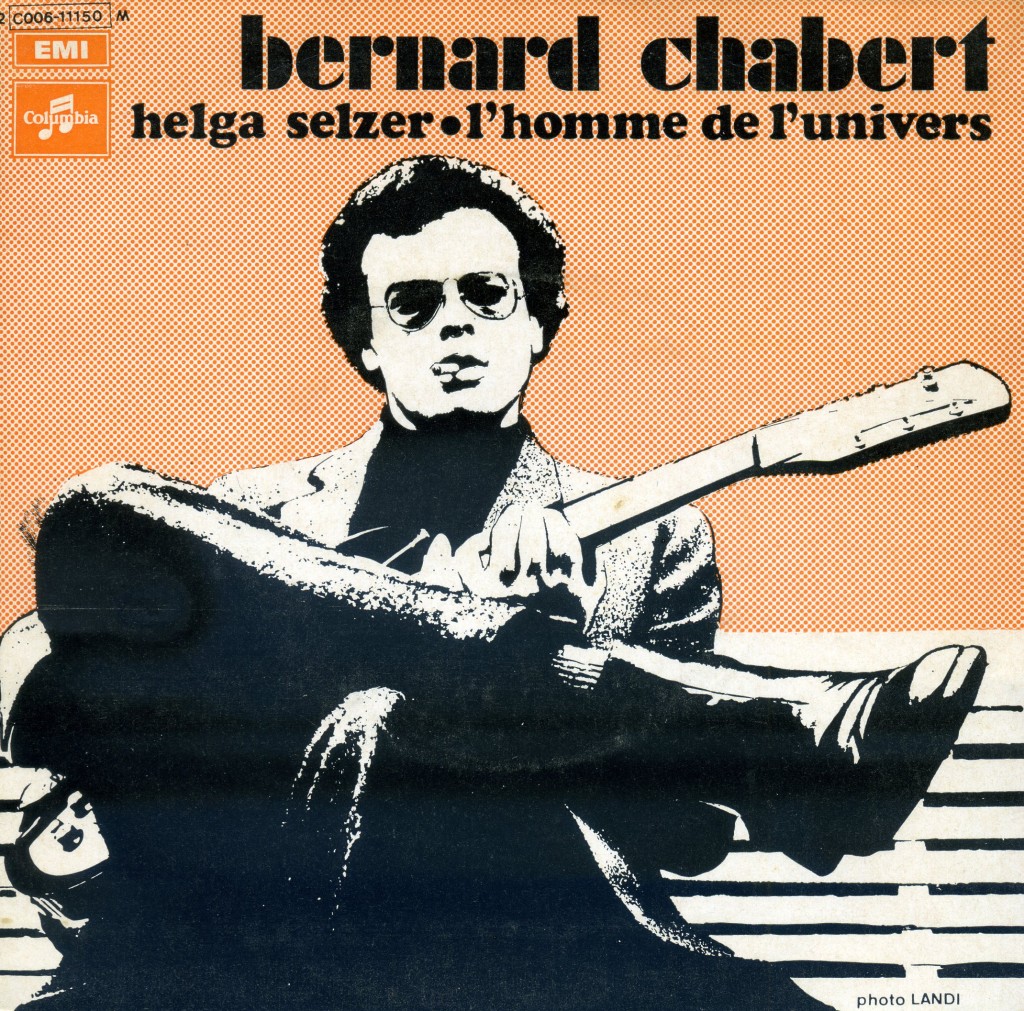

BERNARD CHABERT – Helga Selzer (1970) / Sur une plage bordée de cocotiers (1969)

« Those who don’t believe in Chabert, are the same who in seventeen hundred and some peanuts, didn’t believe in WOLGANG A. MOZART » peut-on lire au dos de la pochette de son premier 45T. Même si la reconnaissance du public tarde encore un peu à venir, on ne saurait lui donner tort tant ses quatre 45t sortis confidentiellement sont étonnants.

Son père fut pilote à l’Aéropostale et sa mère, Rose-Marie Capelli, était écrivain, issue d’une famille de littérateurs italiens. La famille réside à Madagascar où Bernard Chabbert apprend à piloter des avions dès l’âge de 15 ans. Il se destine à devenir pilote de ligne mais c’est sans compter sur ses problèmes de vue qui mettront un terme définitif à ses ambitions.

A défaut d’être pilote de ligne, Bernard sera journaliste. C’est à l’occasion d’un stage de formation à l’école de radio l’OCORA (Office de coopération radiophonique) de Maison Laffite qu’il rencontre son professeur Patrice Blanc Francart. Cette rencontre sera déterminante car si dans son coin, Bernard écoute déjà du rock and roll, et bricole au piano quelques morceaux, il est loin de se douter qu’il va bientôt avoir l’opportunité de sortir des disques.

En effet, Blanc Francart vient d’être embauché chez Pathé Marconi comme Directeur Artistique en charge du catalogue « rock ». Il appelle Bernard pour le convaincre de faire un disque avec lui. Rebaptisé pour l’occasion Chabert avec un seul « b », ils éditent ainsi le premier EP « Sur une plage bordée de cocotiers » (1968) dont la vulgarité tourne rapidement au suicide commercial dans la France bien pensante de l’époque. Un morceau polémiste contre l’avènement de la culture du soleil, du farniente et du bronzage, orchestré notamment par l’explosion du Club Med. Lui qui a grandi sur les plages de Madagascar et s’y est ennuyé toute sa jeunesse, il a bien l’intention que cela se sache !

Lui qui a grandi sur les plages de Madagascar et s’y est ennuyé toute sa jeunesse, il a bien l’intention que cela se sache !

Vont suivre deux autres disques, plutôt réussis eux aussi (le EP Tramway 7B, et le single « Easy Lazie Lizzy ») mais sans davantage de succès.

Au sein de Pathé, Bernard découvre une nouvelle famille. Outre Hubert Rostaing qui réalisera tous ses 45T, Bernard se sent proche d’Isabelle de Funès (La nièce de Louis qui a fait quelques disques excellent de bossa), et Michel Berger alors en pleine période « Puzzle ».

Il écrit tous ses textes ce qui est assez rare pour l’époque. Pour son quatrième et dernier 45 tours, il enregistre alors le détonnant « Helga Selzer ». Le morceau lui est inspiré par Maya, un mannequin vedette à la dérive de chez Chanel qu’il fréquente. Le morceau est enregistré en deux jours. Bernard fait les parties de guitares, et pour les prises de voies, il chante dans un téléphone donnant ainsi au morceau ce rendu final si particulier. Pour la Face B, Hubert Rostaing convie les Variations pour l’accompagner dans une reprise peu inspirée du « Neantherdal man » des Hotlegs…

Comme beaucoup d’artistes de l’époque, Bernard n’aura pas fait de concerts, les opportunités d’avoir un backing band et des engagements étant rares pour les artistes débutants. Il fera quelques passages TV pourtant. Il interprète par exemple “Tramway 7B” à la télévision, le 5 septembre 1969, dans Tous en scène, émission présentée par les Charlots, et participera à diverses émissions avec Jean-Christophe Averty.

Mais la frustration gagne Bernard, lassé par le jeu de la promo, déçu de ne pouvoir faire de concerts. Il cherche une reconversion et veut renouer avec sa carrière de journaliste avortée.

Il commence ainsi une nouvelle carrière chez Europe 1 où il est brièvement chargé de la circulation routière et des grands week-ends de départ en vacances.

En 1970 il devient enfin reporter. En pleine période de la conquête spatiale, le premier « sujet » qui lui est confié par Jean Gorini, directeur de l’information, est la couverture de la fin du programme Apollo à Houston (Apollo 14, 15, 16 et 17), puis Skylab 1, 2 et 3 et ensuite le programme STS (navette spatiale) ainsi que les débuts en URSS des missions astronautiques à participation française. A l’occasion de ses nombreux voyages à Houston où se trouve le centre de formation des astronautes américains, il va découvrir la nuit dans les clubs de la ville une multitude de groupes qui feront sur lui une forte impression. Il y verra ainsi à plusieurs reprises les furieux Moving Sidewalk, formation garage punk culte qui deviendra quelques années plus tard ZZ Top.

En 1970 il devient enfin reporter. En pleine période de la conquête spatiale, le premier « sujet » qui lui est confié par Jean Gorini, directeur de l’information, est la couverture de la fin du programme Apollo à Houston (Apollo 14, 15, 16 et 17), puis Skylab 1, 2 et 3 et ensuite le programme STS (navette spatiale) ainsi que les débuts en URSS des missions astronautiques à participation française. A l’occasion de ses nombreux voyages à Houston où se trouve le centre de formation des astronautes américains, il va découvrir la nuit dans les clubs de la ville une multitude de groupes qui feront sur lui une forte impression. Il y verra ainsi à plusieurs reprises les furieux Moving Sidewalk, formation garage punk culte qui deviendra quelques années plus tard ZZ Top.

En parallèle, dans les années 1970, il devient rédacteur pour de grands journaux aéronautiques comme Aviasport, en France, et correspondant pour le magazine anglais Pilot. En 1972, il adhère à ce qui deviendra l’amicale Jean-Baptiste Salis à La Ferté Alais dont il commente toujours le meeting annuel de la Pentecôte chaque année depuis 1974. En 1991, il lance grâce à Jean Marie Dupont, directeur de France 3 Aquitaine, une émission sur France 3 : Pégase. Il en est le producteur et présentateur, la réalisation étant confiée à Bernard Besnier. Cette émission basée à Bordeaux était l’équivalent du célèbre Thalassa sur la même chaîne, mais appliquée au monde de l’aéronautique. En 2003, il relance Pégase, avec Philippe Guillon, mais cette fois-ci sur Internet.

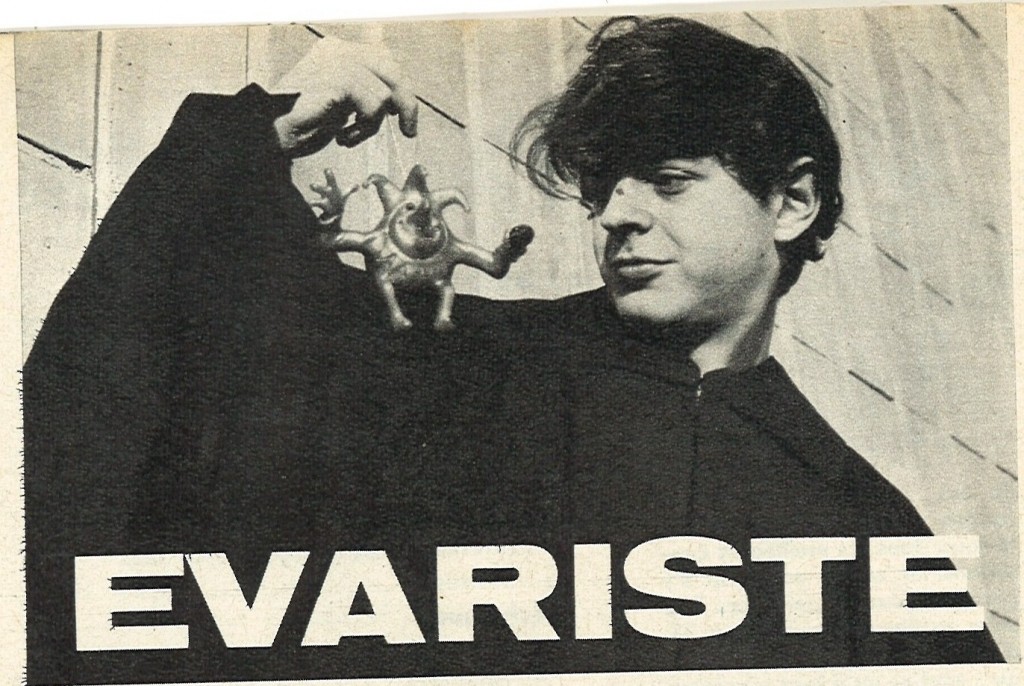

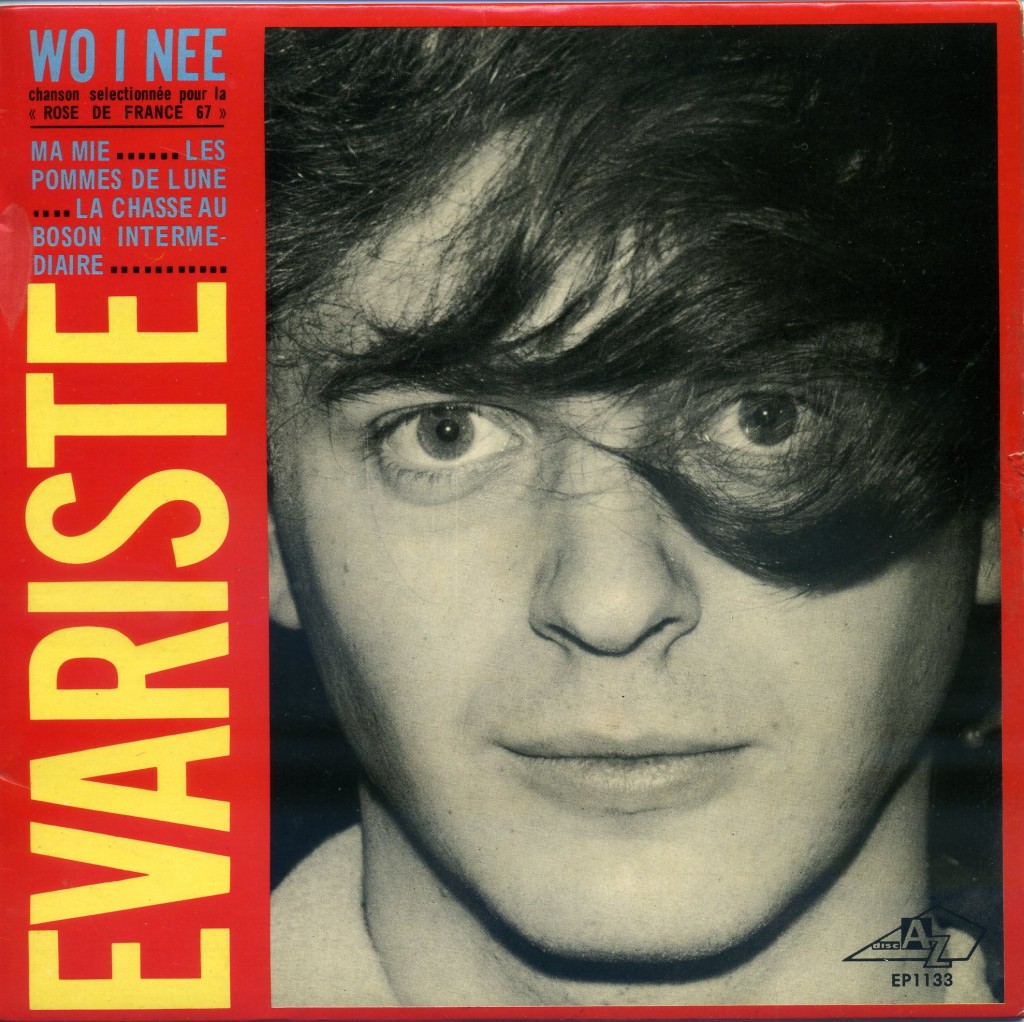

EVARISTE – Les pommes de Lune (1967)

EVARISTE – Les pommes de Lune (1967)

Si le jeune Joël, alias Évariste, arbore un pull aux couleurs de l’université de Princeton, c’est parce qu’il en revient tout juste. Envoyé là-bas pour poursuivre ses recherches sur « la masse des particules, l’interprétation des régularités qu’on y observe comme les conséquences d’une onde » (comprendra qui peut), il arrive aux États-Unis en pleine guerre du Viêt-Nam. À l’époque, Mac Namara cherche une alternative à l’arme nucléaire et sollicite les brillants cerveaux du pays pour s’atteler à la tâche. S’opère alors une « réorientation de crédits » au sein de l’université, formule diplomatique signifiant que ceux qui ne veulent pas marcher dans les combines du gouvernement sont priés de disposer. Joël est sous la tutelle d’un physicien rebelle et se voit donc remercié. L’étudiant reste quand même inscrit aux prestigieux séminaires de l’Institute For Advanced Study, tenus par Oppenheimer, le créateur de la bombe atomique.

Sans doute galvanisé par le mouvement et la musique hippie, Joël s’achète une guitare et se plante dans Washington Square, se disant qu’après tout, Bob Dylan lui-même a débuté là-bas. Il sèche allègrement Oppenheimer et reçoit un accueil chaleureux (quoi qu’étonné) de la part d’une foule qui ne pipe pas un mot de Français. Un jour que le vieux physicien vient l’interroger sur ses absences répétées, il explique à son professeur à quel point la musique l’attire, mais surtout qu’il y voit un moyen de se faire un peu d’argent pour financer ses recherches de manière autonome. Évariste confie avoir vu cet homme malade, au visage ravagé par le remord d’Hiroshima, s’éclairer à ses propos et s’écrier « Oh ! Mais allez-y enfin, foncez ! Si j’étais jeune, c’est absolument ce que je ferais. » L’étudiant reçoit ces mots comme un testament. Des mots qui achèvent de le convaincre qu’il doit sauter le pas. Il plie bagages, direction Paris.

Un ami journaliste qu’Évariste croise souvent dans le quartier de la Sorbonne l’introduit auprès du Directeur Artistique des Disques AZ. Ce dernier passe les bandes au patron du label, Lucien Morisse, qui est aussi directeur des programmes sur Europe N°1. Morisse crie au génie… et signe le chanteur illico ! Nous sommes en 1966 et le phénomène Antoine (qui, lui, a signé chez Vogue) sévit dans tout l’Hexagone. Les chanteurs présentent des profils similaires : tous deux sont scientifiques et doués d’une grande originalité dans leurs textes. Du pain béni pour les deux maisons de disques qui y voient d’emblée une stratégie commerciale. Elles les montrent en rivaux, mais Évariste se défend encore aujourd’hui de ces commérages de journaux pour midinettes. Évariste connaît vite le succès et embraye sur un deuxième 45 tours. Quelques mois plus tard, Mai 68 explose. Tout est bouleversé.

Évariste écrit une série de chansons d’inspiration engagée et court les soumettre à Lucien Morisse. Quand l’homme qui avait créé Salut Les Copains et épousé Dalida entend la chanson La Révolution, sous forme de dialogue entre un père et son fils, il se décompose. La maison AZ ne peut pas sortir ça, c’est impossible. À ce moment précis, Lucien Morisse va commettre un geste historique dans l’histoire de la musique en France. Navré de ne pouvoir suivre officiellement son chanteur sur ce coup, il l’invite à produire son disque tout seul, mais avec son soutien tacite. Il appelle l’usine de pressage de disques et leur demande de pratiquer les mêmes tarifs pour Évariste que ceux en vigueur pour AZ. Le chanteur et ses musiciens disposent du même studio que pour le disque précédent, chacun jouant gratuitement en attendant le retour sur investissement. Le 45T « La Révolution / La Faute à Nanterre » se vend sous le manteau, boulevard Saint-Michel et alentours. Il s’écoule vite, très vite…le retour sur investissement ne se pas fait attendre.

Évariste continue de chanter à Nanterre, avec « la bande à Jussieu » dans laquelle traine « le jeune Renaud, le p’tit gavroche » comme il le surnomme. Un gars de la bande est parent de Wolinski, il les présente. Les deux s’entendent comme pancarte et slogan, si bien que Wolinski dessine la pochette du disque « La Révolution ».

Quand le réalisateur Claude Confortès décide d’adapter la série de dessins de Wolinski intitulée Je ne veux pas mourir idiot, il propose à Évariste d’écrire la bande originale. Son copain, désormais dessinateur dans Hara-Kiri Hebdo, lui fera souvent de la pub en vertu du principe de « spécial copinage » auquel il tient. Bien que florissante, la carrière d’Évariste touche à sa fin. 1970 inaugure la décennie au cours de laquelle il va faire une découverte déterminante dans le domaine de la science et de la musique. Suite à ça, il se détournera de l’univers de la musique autogérée et des revues gaucho pour se focaliser sur la science. Gardant en tête les encouragements d’Oppenheimer, il peut désormais poursuivre ses recherches en toute indépendance, grâce aux recettes de ses disques.

Joël réalise en effet qu’en décodant les séquences des protéines, on découvre des séquences musicales reconnaissables par l’homme. Il les dénomme protéodies. Si l’homme, à l’écoute d’une protéodie, y est sensible au point de la trouver belle, cela signifie qu’il est en carence de la protéine correspondante. Cette musique très singulière pourrait alors le soigner l’être humain. On peut retracer l’histoire de la musique à la lumière des protéines en déficit chez tel ou tel artiste, ou sur une majorité du public.

Joël réalise en effet qu’en décodant les séquences des protéines, on découvre des séquences musicales reconnaissables par l’homme. Il les dénomme protéodies. Si l’homme, à l’écoute d’une protéodie, y est sensible au point de la trouver belle, cela signifie qu’il est en carence de la protéine correspondante. Cette musique très singulière pourrait alors le soigner l’être humain. On peut retracer l’histoire de la musique à la lumière des protéines en déficit chez tel ou tel artiste, ou sur une majorité du public.

Vous avez toujours cru que les groupies hystériques, qui jettent leurs culottes avec passion et s’évanouissent dans la fosse, étaient apparues subitement parce qu’on avait jamais rien vu d’aussi beau que les Beatles ? Faux ! Pour Évariste, tout est affaire d’intro protéinée. Le début de leur premier tube Love me do correspond à la dopamine, soit le neurotransmetteur qui pousse à l’achat compulsif. Une intro pareille ne pouvait que déchainer les chignons des groupies, victimes de la mode et de la biologie.

Il a si bien vendu que ses revenus de musicien lui apportent longtemps l’autonomie financière à laquelle il aspirait déjà quand il se confiait à Oppenheimer. Le scientifique a pu ainsi exercer ses recherches sans aucune contrainte institutionnelle. Il se consacre désormais à ses protéodies, installé dans les bureaux de l’Université Européenne de la Recherche, qui siège à deux pas de la Sorbonne qu’il a si bien connue. Évariste n’est plus. Joël a repris le contrôle de cette bête étrange et drolatique.

LONG CHRIS – Nevralgie particulière (1967)

Long Chris, de son vrai nom Christian Blondieau, est né à Paris le 26 janvier 1942. Avec son groupe Les Daltons, Long Chris sera l’un des pionniers du rock and roll en France dès 1962. Si son groupe ne connaitra jamais le succès des Chaussettes Noires et autres Chats Sauvages, Long Chris n’en sortira pas moins une dizaine de EP chez Philips. Le morceau “Névralgie Particulière “ ici compilé est issu de son unique album “ Chansons bizarres pour gens étranges” (1966).

Si sa propre carrière d’interprète ne rencontre que peu de succès, c’est en réalité en tant qu’auteur-compositeur que Long Chris va obtenir la reconnaissance qu’il mérite. Ami d’enfance de Johnny Halliday, il va ainsi écrire tout au long de sa carrière de nombreux tubes pour son ami comme La génération perdue, Je suis né dans la rue, Gabrielle et Joue pas de rock’n’roll pour moi.

Christian Blondieau est aujourd’hui un spécialiste des antiquités militaires et l’auteur de nombreux ouvrages historiques. Il possède un magasin d’antiquités dans le quartier du Village Suisse à Paris et travaille également comme expert en ventes publiques auprès des commissaires priseurs.

JOANNA – Hold up inusité (1969)

Quoi, Joanna serait belge ? Oui, bon, vous ne faites pas tant d’histoires quand il s’agit de Johnny, Brel, Adamo ou Annie Cordy.

PAPY – Toi le Shazam(1967)

« Les hippies de San Francisco ne sont désormais plus seuls, leur mouvement a traversé l’Atlantique, et a déferlé sur nos côtes. Le premier à se réclamer des leurs est un peintre de Montmartre, il s’appelle Papy. Il chante « Toi le Shazam » qui est le nom du grand prêtre des hippies et son mode de vie se résume en trois phrases :

Fais ce que tu veux, quand tu veux, où tu veux »

Tout un programme que l’on peut lire au dos de la pochette du second 45 tours (Vogue -1967) du mystérieux Papy, ainsi propulsé sans doute bien malgré lui chantre des hippies made in France par les chefs de produit opportunistes de chez Vogue. A part cela, Papy, de son vrai nom François Papi aurait été peintre sur la butte à Montmartre. Il y peignait au kilomètre des poulbots pour les touristes. On découvre sa collaboration avec Claude Perraudin le temps de ce 45 tours et d’un suivant sur lequel figure l’excellent « Machine ». Chez Born Bad Records, on aime bien Claude Perraudin, ancien collaborateur de Gainsbourg, Claude François ou encore Jacques Dutronc qui composa de nombreux disques d’illustration sonore dont le chaudement recommandé album « Mutation 24 ». En 1984, Papy sortira un tardif et ultime 45T « On revient toujours au pays ».

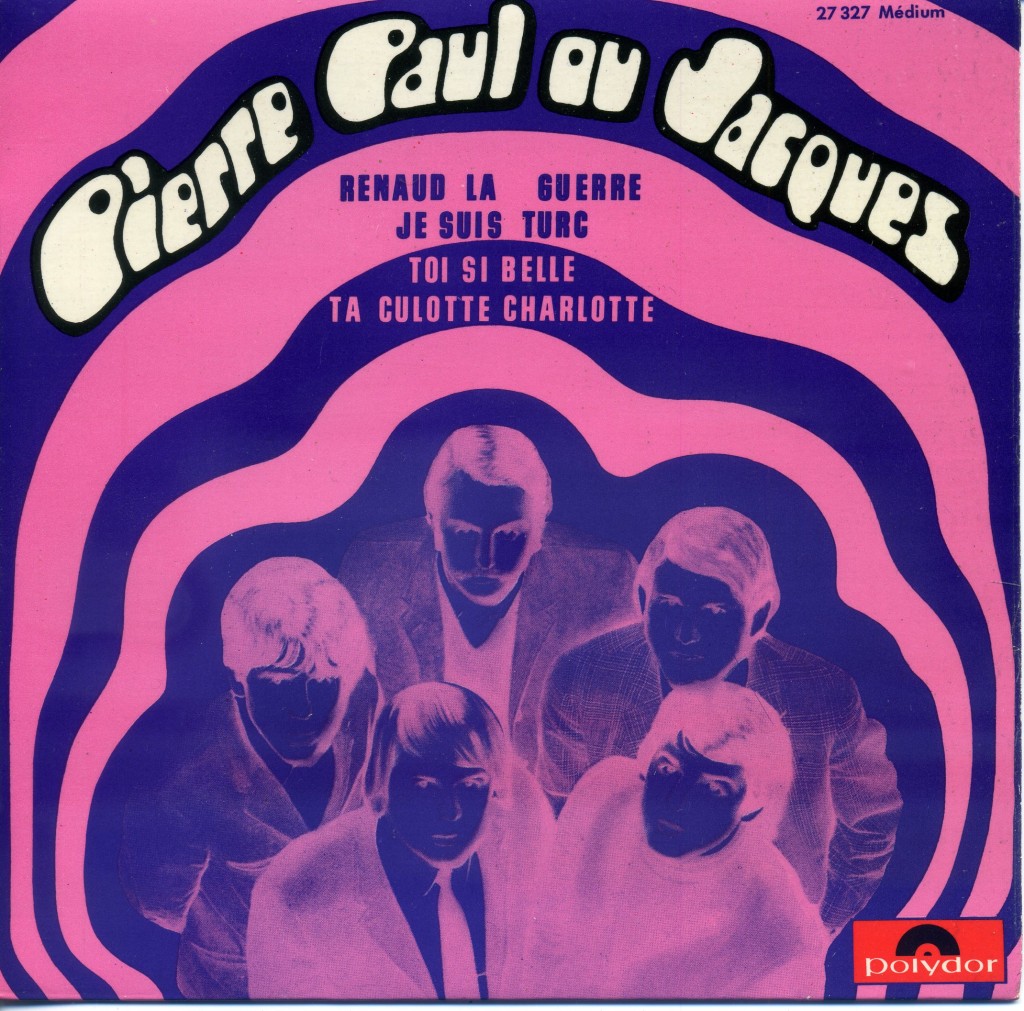

PIERRE, PAUL OU JACQUES – Je suis Turc (1967)

PIERRE, PAUL OU JACQUES – Je suis Turc (1967)

Encore un projet né de l’imaginaire fantasque de Richard Bennet (aka William Benett), Directeur artistique audacieux et téméraire de chez Barclay, découvreur entre autre de Nino Ferrer. Comme d’habitude, on trouve aux manettes de ce curieux disque des Pierre, Paul ou Jacques, son groupe de prédilection les Piteuls, emmené par Serge Koolenn et Richard Dewitt (Deux futurs « Il était une fois »). On se souvient que c’est déjà à eux que Richard avait confié la réalisation du terrifiant et LSDique 45Tours des Papyvores (CF Wizzz Vol1), et du Buddy Badge Montezuma.

L’instrumental de « Je suis turc » sera recyclé une nouvelle fois via le délirant morceau « Ma ceinture Papa, j’ai peur Maman » sur l’unique 45 tours de Patrick Bernard. Pour mémoire, et ceux qui n’ont pas la chance de posséder la compilation WIZZZ volume 2, ce sont bien les Piteuls qui mutèrent ensuite en Bain Didonc (Rappelez-vous le terrifiant « Quatre cheveux dans le vent ») puis en Jelly Roll (Je travaille à la caisse)

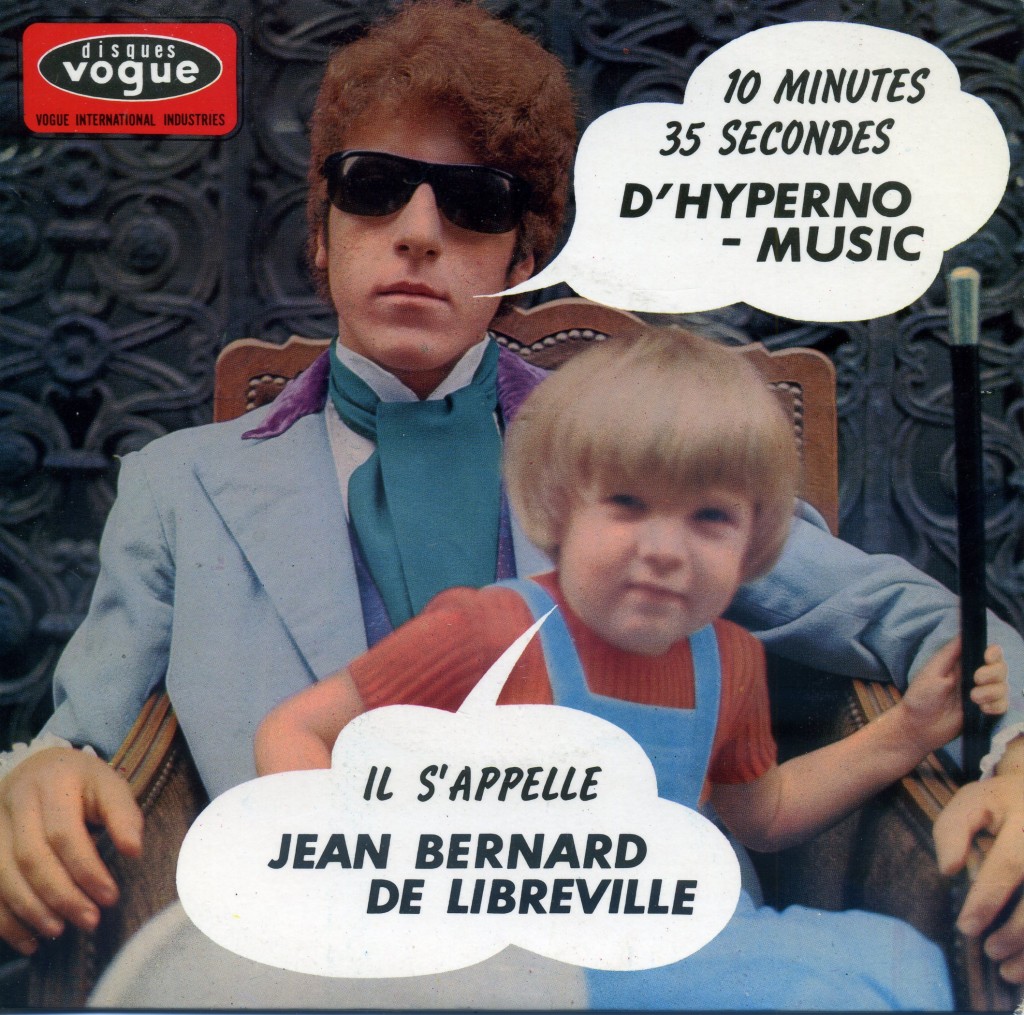

JEAN-BERNARD DE LIBREVILLE – La juxtaposition 210 (1966)

JEAN-BERNARD DE LIBREVILLE – La juxtaposition 210 (1966)

C’est Germinal Tenas, directeur artistique de chez Vogue qui sera à l’origine de l’ambitieux Ep de Jean-Bernard de Libreville qu’il produit en 68 : Rencontre conceptuelle du dandysme, du surréalisme et du punk avant l’heure. Ce disque visionnaire, déglingué et foutraque trouvera un accueil dithyrambique dans la profession mais pas auprès d’un public toujours aussi autiste et frileux. Le disque de Jean-Bernard de Libreville reste encore à ce jour l’un des plus beaux Ovni musicaux produits en France.

Fuyant la guerre d’Algérie, Chaib Bouri a 5 ans lorsqu’il atterrit en France avec ses parents dans la cité HLM du Bel-air à Montreuil sous Bois (93). Sa mère lui offre pour ses 10 ans une guitare et c’est en autodidacte qu’il commence à composer quelques morceaux déjà décalés en écoutant les Beatles, les Rolling Stones, et Bob Dylan. A 15 ans, Chaib décide d’aller auditionner chez Vogue. Christian Fechner et Germinal Tenas, les directeurs artistiques du label sont séduits par le jeune adolescent. Germinal Tenas, plus excentrique tu meurs avec son singe sur l’épaule, sa chemise à fleurs et son cigare signe donc Chaib chez Vogue pour quatre 45 tours.

Rebaptisé par Germinal Jean-Bernard de Libreville – c’est plus chic – il est rapidement convenu d’enregistrer un premier disque (1966).

Sur des textes et musique de Chaib, Germinal expérimente, et laisse aller sa créativité débridée : bandes passées à l’envers, rythmiques bruitistes, musique répétitive et singulière que Germinal baptise L’hyperno-music. Ce disque unique en son genre est un véritable ovni dans la production de l’époque.

Pour compléter ce disque conceptuel et avant-gardiste, Germinal à besoin d’un personnage à la hauteur de la démence du disque. Chaib se doit ainsi d’incarner de toute pièce un énigmatique dandy au look très sophistiqué (Redingote victorienne, cravate foulard, canne à pommeau, lunettes de soleil qu’il pleuve ou qu’il vente).

Rien n’est laissé au hasard. La pochette du EP, avec une photo prise par Michel Quennville, le mari de Claire Bretecher, renforce encore l’aura mystérieuse de Jean-Bernard de Libreville. Chaib y apparait majestueusement insolent, le cigare à la bouche, avec un enfant sur les genoux.

A la sortie du disque, la profession salue unanimement l’audace de Germinal Tenas. L’avenir semble radieux pour Chaib et Il est déjà question de faire un Olympia.

L’organisation d’une conférence de presse pour le lancement du EP en fanfare est orchestré et mis en scène par Tenas. Il ne faut pas décevoir et le lancement doit être à la hauteur du personnage imaginé par lui. Toute une mise en scène proche du happening est ainsi orchestrée par Vogue. Chaib arrive ainsi triomphalement dans une boite des champs Élysée, sortant d’une somptueuse Jaguar et entouré de gardes du corps. Il déboule accompagné de sirènes stridentes et hurlantes, de banderoles géantes « Juxtaposition 210 » devant un parterre de journalistes médusés. Jean-Bernard est censé délivrer son petit numéro de dandy déglingué savamment répétée avec Germinal. Mais Chaib du haut de ses 15 ans se sent dépassé, trop impressionné, il perd ses moyens, et la petite sauterie de Germinal tourne au désastre. Tétanisé, enfermé dans un mutisme profond, Jean-Bernard se révèle incapable de prendre la parole. La farce tourne au cauchemar.

S’ensuit une virulente engueulade entre Germinal et Jean-Bernard. Excédé par les manipulations de Germinal qui projette tous ses délires sur lui, Jean-Bernard refuse d’honorer ses engagements. Il n’y aura pas d’autres 45 tours, Il refuse de continuer à travailler avec son mentor. Le contrat est résilié, l’Olympia annulé, et Jean-Bernard jeté aux oubliettes du showbiz.

S’ensuit une virulente engueulade entre Germinal et Jean-Bernard. Excédé par les manipulations de Germinal qui projette tous ses délires sur lui, Jean-Bernard refuse d’honorer ses engagements. Il n’y aura pas d’autres 45 tours, Il refuse de continuer à travailler avec son mentor. Le contrat est résilié, l’Olympia annulé, et Jean-Bernard jeté aux oubliettes du showbiz.

Quelques années ont passé (1969) et Christian Fechner qui a été licencié de chez Vogue vient de monter sa propre boite. Fechner recherche un artiste pour sortir un album potache et sulfureux sensé surfer sur la vague d’indignation suscité par la sortie du « Je t’aime moi non plus » du duo Birkin-Gainsbourg. Entre chansons paillardes et gauloiseries, Jean-Bernard accepte de faire cet album de commande. Accompagné pour l’occasion des Haricots Rouges, le disque est rapidement mis en boite. Pas toujours très inspiré, souvent balourd, Fechner n’est que moyennement enthousiaste à l’issue de ces sessions d’enregistrement. Il vient de se lancer dans le cinéma avec les Charlots et tout cela lui semble désormais bien secondaire. Fechner se désintéresse peu à peu du projet et Jean-Bernard reste finalement avec cet album sur les bras.

Les années passent, et début 70, alors que Jean-Bernard est dans une casse automobile pour trouver une pièce pour réparer sa vielle Rover, il tombe par hasard sur Hilary Cus, un ancien de chez Vogue. Ce dernier monte désormais des concerts et tournées en métropole pour des groupes Antillais. Hilary qui vient de monter sa propre boite d’édition Dayvis, accepte de sortir sur deux 45 tours quatre des morceaux issus des sessions d’enregistrement avec Fechner. C’est ainsi que les singles « Allons y gaiement / Du Miles Davis » et « Sexo-phone / Les pipes » voient le jour de façon confidentielle.

Chaib abandonne peu de temps après définitivement son pseudonyme de Jean-Bernard de Libreville. Les années qui suivent sont difficiles. Continuant comme il peu, il joue pas mal dans le métro et sort quelques disques sous différents noms (Cyril Savine, Chaib).

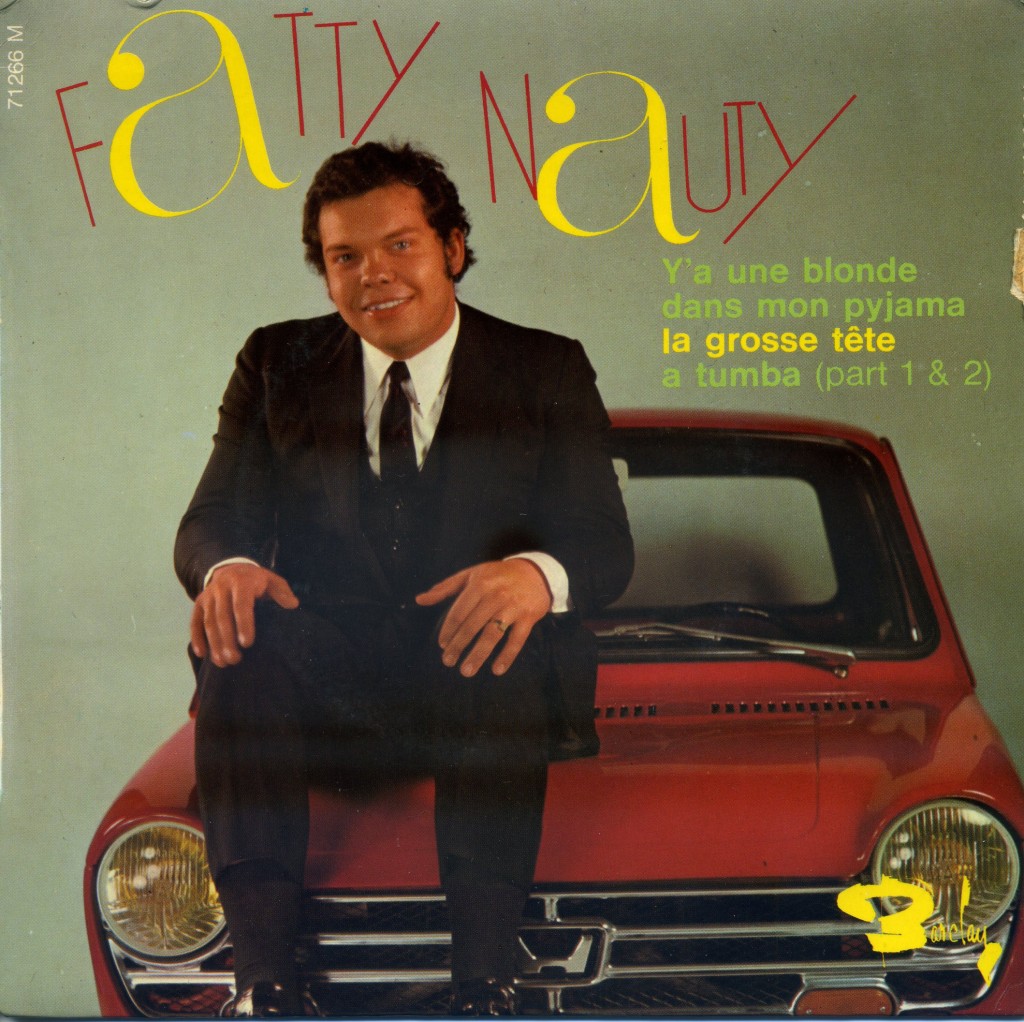

FATTY NAUTY – A tumba Part 2 (1968)

FATTY NAUTY – A tumba Part 2 (1968)

Bernard Paganotti, né à Oran en Algérie, fonde avec Christian Vander le groupe Chinese (1967) qui se rebaptise rapidement Cruciferius Lebonz. En 1968 Paganotti sort chez Barclay le EP de Fatty Nauty n’ Cruciferius Lobonz dont est extrait “Tumba” ici compilé. Ils font quelques dates en première partie de Ronnie Bird et David Alexandre Winter, mais sans succès.

En 1967 après le départ de Christian Vander partie fonder Magma, Bernard continue le groupe en compagnie de François Bréant, Patrick Meru et Patrick Jean. Sous le nom de Cruciferius ils enregistrent un album qui reste encore à ce jour l’un des chefs d’œuvre du rock progressif français. Le groupe ayant splitté au début des années 70, Bernard rejoint alors son ami Vander au sein de Magma. En septembre 1976 Bernard quitte Magma et forme Weidorie

Bassiste d’exception, Bernard devient l’un des bassistes français les plus demandés au cours des années 80. Il enregistre ainsi avec Francis Cabrel, Johnny Halliday, Mylène Farmer, Vanessa Paradis pour n’en citer que quelques uns.

Vous l’aviez découvert sur la WIZZZ volume 2 avec le déflagrateur « Maintenant je suis un voyou », il revient avec cet inédit de premier ordre.

Mais remontons le temps… Début 67, Bruno est en fac de médecine à Paris. En rentrant de l’université en voiture avec un de ses potes, Bruno chante nonchalamment par-dessus les morceaux que diffuse l’autoradio. Son ami est étonné de découvrir son joli brin de voix et l’encourage à auditionner pour un groupe d’amis de la fac qui recherche leur chanteur. Bruno ne sera pas choisi à l’issue des auditions, mais se liera d’amitié avec un des membres du groupe, Emmanuel Pairault.

Emmanuel, de son côté, suit des cours d’économie qu’il décide d’arrêter pour s’inscrire au conservatoire afin d’apprendre les percussions et l’utilisation des fameuses ondes Martenots.

Il compose ainsi quelques titres en solo dont la singularité est d’utiliser ces ondes. Il cherche quelqu’un pour mettre en paroles ses morceaux et propose à Bruno de lui écrire quelques textes. Bruno et Emmanuel développent ainsi rapidement un petit répertoire sans autre ambition que celle de s’amuser. Dans des circonstances désormais oubliées, ils font tout de même passer leur titre à Nicole Croisille qui leur suggère d’envoyer leur maquette à son ami Norbert Saada, le patron du label La Compagnie.

Saada est séduit par cette utilisation inédite des ondes Martenots dans des chansons pop. Il leur propose de suite d’enregistrer un disque. Emmanuel Pairault réunit ainsi rapidement une petite équipe pour les besoins de l’enregistrement. Les sessions se déroulent rue de la Gaîté au studio de Dominique Blanc Francart avec Bernard Lubat aux percussions, François Rabath à la contrebasse, Jimenez et Jean-Pierre Dariscuren aux guitares, Emmanuel Pairault et Sylvain Gaudelette aux ondes Martenots, et bien entendu Bruno au chant. Quatre titres sont ainsi enregistrés pour les besoins du EP à venir (« Maintenant je suis un voyou », « Eve », « Hallucinations », et « Galaxie »)

Les sessions terminées, Bruno se voit dans l’obligation de partir au service militaire et perd un peu le contrôle des opérations. Norbert Saada presse un 45t promotionnel pour tenter de trouver une licence sur le marché canadien mais en vain. Pour les collectionneurs, ce très rare 45t couple les titres « Maintenant je suis un voyou » et « Galaxie ».

Au son retour du service, Bruno apprend que Norbert Saada se retire des affaires et a vendu son catalogue mettant ainsi un terme à tout espoir de voir un jour son disque sortir (1969). Le morceau “Eve” est ainsi resté jusqu’à ce jour inédit.

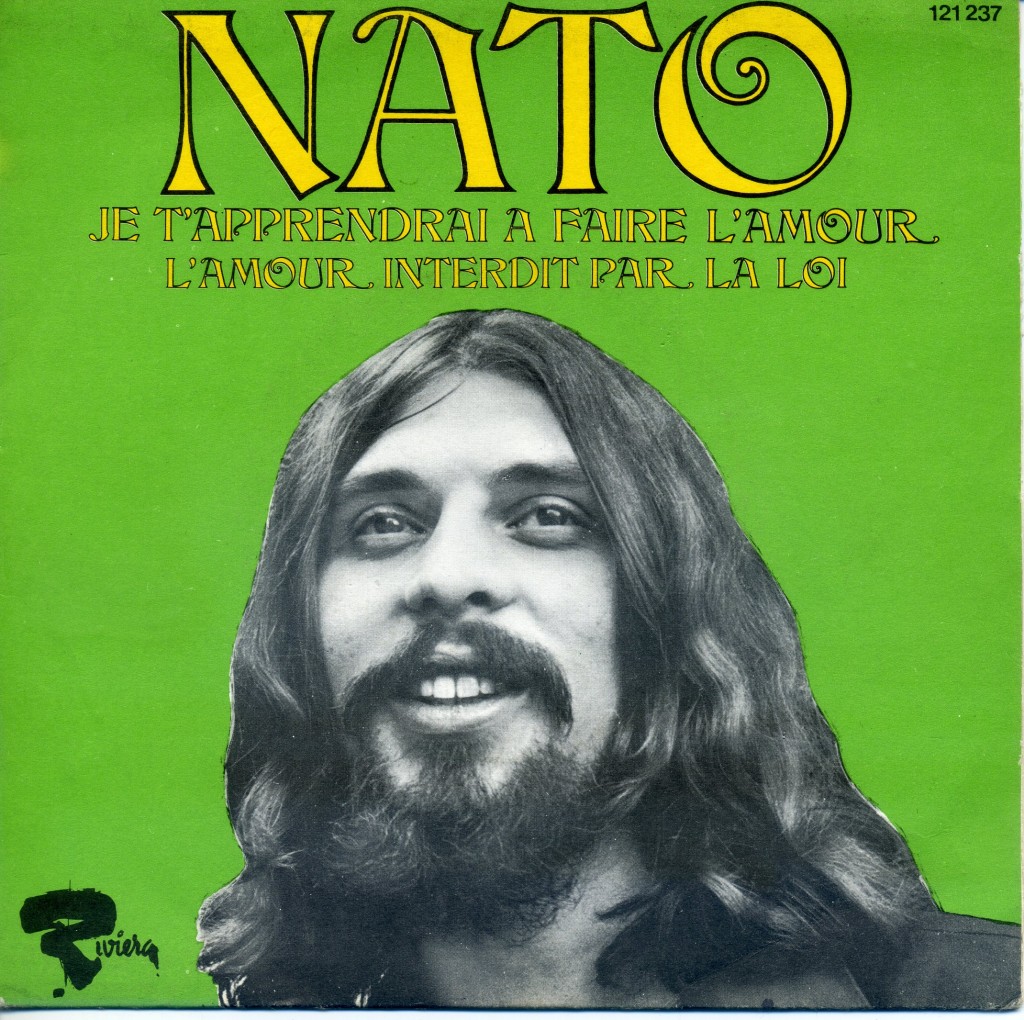

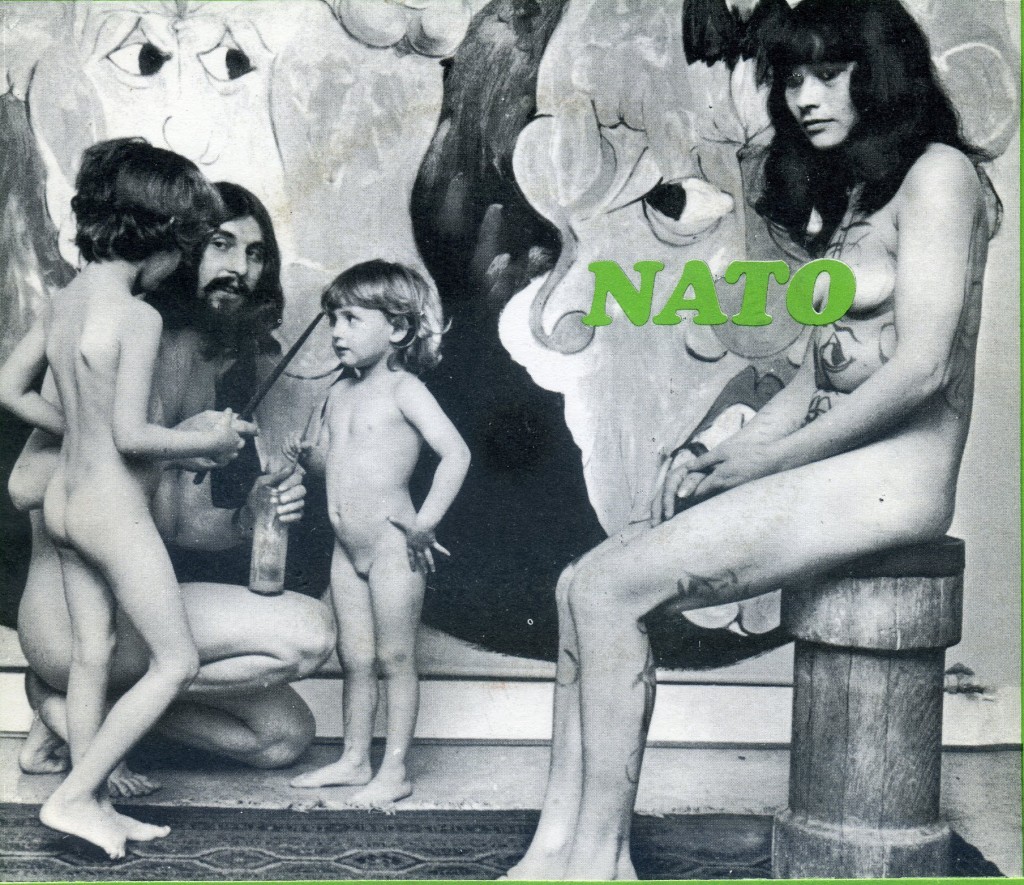

NATO – Je t’apprendrai à faire l’amour (1969)

NATO – Je t’apprendrai à faire l’amour (1969)

Nato est né en 1944 en Belgique dans un milieu bourgeois (Père haut fonctionnaire et mère catholique très pratiquante) où il reçoit une éducation religieuse extrêmement stricte. Il étudie au Collège de St Luc, le pendant belge de nos Beaux Arts, et se découvre très tôt une passion pour la peinture.

Son premier boulot à l’issue de l’école, il le décroche à la Sabena (l’équivalent belge d’Air France) comme décorateur. Mais très vite ce marginal qui s’ignore encore étouffe et démissionne pour se concentrer uniquement sur son art qui devient global. Nato touche à tout : Peinture, performance, sculpture, musique, cinéma. Il jouera d’ailleurs dans plusieurs longs métrages de son ami Christian Mesnil dont le mystérieux “Psychedelissimo”.

Rapidement sa peinture devient érotique et le sexe devient central dans son travail. En 1968, Nato signe chez Riviera et sort simultanément deux 45tours détonnant: “L’amour interdit par la loi / Je t’apprendrai à faire l’amour”, et “Marijuana / Faire l’amour / Tu ne dis pas ça/ Le grand voyage” (1969) qui sont trop provocateurs pour trouver leur public.

Clairement hippies et subversives, ses chansons sont autant d’odes à la fornication, l’amour libre, et les paradis artificiels, ce qui manifestement ne plaît pas à tout le monde.

Face au peu de succès rencontré, Nato se concentre sur la peinture. Il multiplie les expositions, et les happenings dans toute la Belgique.

En 1974, il enregistre avec le groupe suédois Lady Pain, l’album “Actuel Un” (Barclay) et part s’installer à Paris avec femme et enfants. Dans les années qui suivent Nato qui ne cesse les projets artistiques sortira encore les albums conceptuels « F.M. Accoustic », et « Triple objet créatif de consommation auditive »(1982) sans d’avantage de succès. Des disques eux aussi bien barrés comme on dit pudiquement.

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Translation : Jon von Zelowitz

One, two, three… hold your breath during the next forty minutes for a peregrination through a special kind of pop music “made in France,” a mix of ribaldry, flashes of brilliance and adventurous twists on familiar sounds. We will plunge into French-style pop, unapologetic and defiant; Blue-White-and-Red pop that does not take itself seriously, not particularly displeasing its “yéyé” contemporaries, themselves lacking inspiration as they listened to the boring, commercial teenage music that predominated in France at that time. It is pop music fueled by creativity – though not always well focused – with peculiar arrangements, inspired compositions and precarious production… but oh, it’s so tasty!

WIZZZ 3 spotlights French artists who dared to try, to experiment…

BERNARD CHABERT – Helga Selzer (1970) / Sur une plage bordée de cocotiers (1969)

“Those who don’t believe in Chabert, are the same who in seventeen hundred and some peanuts, didn’t believe in WOLFGANG A. MOZART,” according to the notes on the back of his first 45. Public acclaim has been slow to arrive, yet we must agree with the liner notes, because his four limited-edition 45s are truly amazing.

Chabbert’s father was a pilot for Aéropostale (a pioneering French airline) and his mother, Rose-Marie Capelli, was a writer, following in the tradition of her Italian family. The family lived in Madagascar, where Bernard learned to fly airplanes at the age of 15. He was on his way to becoming an airline pilot, but poor eyesight forced him to change his career plans.

Instead, he became a journalist. Studying for a career in radio at the OCORA in Maisons-Laffitte (west of Paris), one of his instructors was Patrice Blanc Francart. This turned out to be a crucial encounter: although Bernard was already listening to rock ‘n’ roll and tinkering with a few songs on the piano, he never suspected that he was on the verge of making records.

In fact, Blanc Francart had just been hired by Pathé Marconi (a large media conglomerate) as the A&R man for their rock ‘n’ roll catalog. He called Bernard and convinced him to collaborate on a record. Temporarily rebaptized “Chabert” (with a single “b”), he put out a first EP entitled “Sur une plage bordée de cocotiers (On a beach lined with coconut trees)” (1968), whose vulgarity was suicidal in the conservative-minded France of that era. Bernard enjoyed himself in his own way with this provocative track concerning the advent of the culture of sunlight, relaxation and tanning, particularly based on the rise of Club Med. Having spent his bored youth on the beaches of Madagascar, he wanted to let people know the truth!

Two other discs followed, both rather good (the Tramway 7B EP and the “Easy Lazie Lizzy” single), but no more successful commercially.

Bernard met a whole new family at Pathé. In addition to Hubert Rostaing, who produced all the 45s, Bernard hung out with Isabelle de Funès (the niece of actor Louis de Funès; she made several excellent bossa nova records) and Michel Berger, who was in the midst of his “Puzzle” period.

He wrote all his own lyrics, which was unusual then. His fourth and final 45 was the explosive “Helga Selzer.” At the time, he was hanging out with Maya, a top model adrift from Chanel; she inspired the song, which was recorded in two days. Bernard played the guitar parts. For the vocals, he sang into a telephone, giving the track its unusual sound. On the flip side, Hubert Rostaing brought in the Variations to accompany an uninspired cover of “Neanderthal Man” by Hotlegs (pre-10cc).

Like many artists of the time, Bernard did not play live; novices like him had great difficulties getting a backing band and booking dates. However, he made a few TV appearances. For example, he sang “Tramway 7B” on September 5, 1969, on the Tous en scène TV show, hosted by the Charlots (a jokey pop group), and was on several programs with the legendary Jean-Christophe Averty.

Nevertheless, Bernard was overwhelmed by frustration, left behind in the promo game and disappointed that he couldn’t play live concerts. Seeking to change careers, he tried to get back into journalism.

He got a job at the “Europe 1” radio station, where he was briefly in charge of traffic reports and coverage of holiday weekend traffic jams.

Finally, in 1970, he became a reporter. It was the space age, and Jean Gorini, the news director, assigned him to cover the end of the Apollo program in Houston (Apollo 14, 15, 16 and 17), and then Skylab 1, 2 and 3, the STS (Space Shuttle) and the beginnings of manned flights in the USSR with French participation. On his many trips to Houston (the training center for American astronauts), his discovery of the local nightlife left a strong impression. There, he saw the Moving Sidewalks, a wild, cult garage punk group that years later became ZZ Top.

At the same time, in the 1970s, he became a writer for major aeronautical publications such as Aviasport in France, and a correspondent for the English magazine Pilot. In 1972, he joined the “Amicale Jean-Baptiste Salis,” an association based in La Ferté-Alais concerned with historic airplanes. He has written articles in the press concerning their annual Pentecost meeting every year since 1974. In 1991, Jean Marie Dupont, director of the France 3 Aquitaine television channel, gave him a program: Pégase. He was the producer and host; Bernard Besnier was director. This show, based in Bordeaux, was the equivalent of the famous “Thalassa” show on the same channel, with in-depth reports on particular subjects, but applied to the world of aviation. In 2003, he relaunched Pégase on the Internet, together with Philippe Guillon.

ÉVARISTE (1967)

If young Joël, aka Évariste, wears a sweater with the Princeton University insignia, there’s a good reason for it. Sent there to pursue his research on “particle mass and interpretation of mass patterns observed as the consequences of a wave” (in case you manage to understand that), he arrived in the United States at the height of the war in Vietnam. At the time, Robert McNamara, US Secretary of Defense, was looking for an alternative to nuclear weapons and asked the brightest minds in the country to take on this challenge. This gave rise to a “reorientation of funds” within the university, a diplomatic formula meaning that those who did not want to work on these government projects were asked to leave. Joël was under the supervision of a rather non-conformist physics professor, and was therefore shown the door. He remained enrolled in prestigious seminars at the Institute for Advanced Study, run by Robert Oppenheimer, creator of the atomic bomb.

No doubt galvanized by the hippie movement and its music, Joël bought a guitar and set up in Washington Square (New York), since, after all, Bob Dylan started there too. He cheerfully skipped Oppenheimer’s classes and received a warm (while astonished) welcome from a crowd that did not understand a word of French. One day, the aging physicist came to ask Joël about his repeated absences. Explaining how much he was attracted to the music, Joël emphasized that he mainly saw it as a way to make some money to finance his research in an independent manner. Évariste recounts that he saw this sick man, his face ravaged by remorse over Hiroshima, light up in response to this explanation and exclaim, “Oh! You should certainly do it, I encourage you! If I were young, that is absolutely what I would do.” The student perceived this as presaging his destiny, just what he needed to convince him to take the plunge. He packed his bags and headed back to Paris.

A journalist friend whom he often ran into near the Sorbonne introduced him to the head of A&R at Disques AZ. From there, his tapes came to the attention of Lucien Morisse, the head of the label, who was also program director for Europe 1. Morisse thought the music was brilliant… and signed Évariste immediately! This was in 1966, and the Antoine phenomenon (on Vogue records) was resonating throughout France. The two singers have similar profiles: both were trained as scientists, and composed highly-original lyrics. This was a godsend for the two record labels, which instantly identified a lucrative business strategy. They were portrayed as rivals, but Évariste denies it to this day, saying that it was just a lot of gossip in magazines for teenage girls. Évariste quickly had a hit record and got to work on a second one. A few months later, the civil unrest of May 1968 broke out in France. Everything was in upheaval.

Évariste wrote a series of politically-committed songs and quickly sent them to Morisse. But, when Morisse (husband of pop singer Dalida and creator of the popular but mainstream Salut Les Copains radio show) heard La révolution, which portrays a dialogue between a father and son, he flipped out. “AZ can’t put out a record like that! Impossible!” Morisse thus made a momentous decision in the history of French music. Regretful that he could not officially produce the record, he proposed that Évariste put it out himself, but with Morisse’s tacit support. He called the record pressing plant and asked them to charge the same rates for Évariste as for AZ. The singer and his band recorded in the same studio as the previous disc, playing for free pending the profits from sales. The 45 of “La révolution / La faute à Nanterre” was sold illicitly on and around boulevard Saint-Michel. It sold out very, very quickly… and the profits followed.

Evariste continued to sing in Nanterre, with “la bande à Jussieu” (the Jussieu gang), including “le jeune Renaud, le p’tit gavroche (young Renaud, the little street urchin),” as he called him. (Renaud Séchan became a very popular singer-songwriter.) One guy from the gang was a relative of the satirical cartoonist Wolinski, and introduced them. The two got along famously and Wolinski drew the record cover for “La révolution.”

When director Claude Confortès decided to adapt a series of Wolinski’s drawings entitled Je ne veux pas mourir idiot (I don’t want to die stupid), he asked Évariste to compose the soundtrack. Wolinski, by then a cartoonist for Hara-Kiri Hebdo (a satirical weekly), often promoted Évariste under his policy of “spécial copinage” (shameless promotion). Despite his success, Évariste’s career was nearing its end. In the 70s, he made a major breakthrough linking science and music. At that point, he abandoned the world of self-produced music and leftist magazines to focus on his research. Keeping Oppenheimer’s encouragement in mind, he now had the resources to continue his work independently, with the revenues from his records.

Joël realized that decoding protein sequences reveals corresponding musical sequences, which humans can recognize. He called them protéodies. If a person, listening to a protéodie, finds the sounds beautiful, this means he has a deficiency of the corresponding protein. This singular “music” could therefore benefit people’s health. The history of music could be rewritten in light of the protein deficit of a certain artist, or a majority of the public.

You always thought that hysterical fans, who passionately throw their panties and faint in front of the stage, had appeared suddenly because they had never seen anything as wonderful as the Beatles? Wrong! According to Évariste, everything is explained by the protein-perturbing introduction to their first hit, Love Me Do, which corresponds to dopamine, the neurotransmitter that also triggers compulsive buying. An intro like that could not fail to whip up the fans, victims of fashion and biology.

His records sold very well, their revenues bringing him the long-term financial autonomy to which he aspired back when he spoke to Oppenheimer. Joël the scientist was able to carry out his research free of institutional constraints. He devoted himself to studying protéodies at the Université Européenne de la Recherche, just down the street from the Sorbonne he knew so well. Évariste was no more. Joël took back the helm of this strange and amusing beast.

LONG CHRIS (1967)

Long Chris was born Christian Blondieau in Paris on 26 January 1942. In 1962, with his group Les Daltons, Long Chris would become one of the pioneers of rock ‘n’ roll in France. Although his group never had the success of the Chaussettes Noires or Chats Sauvages, Long Chris finished with no fewer than 10 EPs to his credit on the Philips label. The song “Névralgie Particulière” on this compilation comes from his only album, “Chansons bizarres pour gens étranges (bizarre songs for strange people)” (1966).

While his performing career met with only modest success, Long Chris would receive the recognition he deserves for his work as a songwriter. A childhood friend of Johnny Halliday, he wrote numerous hits for France’s preeminent rock ‘n’ roll star, all throughout his career, including La génération perdue, Je suis né dans la rue, Gabrielle and Joue pas de rock’n’roll pour moi.

Christian Blondieau is now a specialist in military antiques and the author of numerous historical works. He has an antique shop in the Village Suisse area of Paris and is retained by auctioneers for expert advice concerning their public sales.

JOANNA – Hold up inusité (1969)

What, it bugs you that Joanna is from Belgium? Come on, you don’t make that much of a fuss about Johnny, Jacques Brel, Adamo or Annie Cordy!

PAPY (1967)

“The San Francisco hippies are no longer alone; their movement has crossed the Atlantic, and has swept onto our beaches. The first to claim a connection was a painter from Montmartre called ‘Papy.’ He sang ‘Toi le Shazam,’ the name of the high priest of the hippies. His lifestyle can be summarized in three phrases:

Do what you want, when you want, where you want.”

Quite a program, indeed! It is detailed on the back cover of the second 45 (Vogue – 1967) of this mysterious artist, surely portrayed against his own wishes as the king of the “made in France” hippies by the opportunistic businessmen at Vogue records. Aside from this, Papy (real name François Papi) was a painter, living in the heights of Montmartre. He cranked out paintings of street urchins to sell to tourists. He collaborated with Claude Perraudin on this 45, as well as on a later one that includes the excellent track “Machine.” At Born Bad Records, we are big fans of Claude Perraudin, who also worked with Gainsbourg, Claude François and Jacques Dutronc, and composed numerous albums of production music, including the highly recommended “Mutation 24.” In 1984, Papy put out his last 45, “On revient toujours au pays.”

PIERRE, PAUL OU JACQUES (1967)

This was another project from the whimsical imagination of Richard Bennet (aka William Benett), bold and daring A&R man at Barclay records, who discovered Nino Ferrer, among others. As usual, he was the recording engineer for this strange disk by Pierre, Paul ou Jacques. His favorite group was les Piteuls, led by Serge Koolenn and Richard Dewitt; both later played in the group “Il était une fois.” We recall that Richard had already entrusted them to make the terrifying, LSD-soaked 45 of the Papyvores (cf. WIZZZ Vol. 1) and Buddy Badge Montezuma.

The instrumental track of “Je suis turc” would be recycled once again on the outrageous “Ma ceinture Papa, j’ai peur Maman” on the only 45 made by Patrick Bernard. As a reminder, notably for those not lucky enough to own WIZZZ Vol. 2, these are the same Piteuls who later mutated into Bain Didonc (who made the terrifying “Quatre cheveux dans le vent”) and then into Jelly Roll (“Je travaille à la caisse”).

JEAN-BERNARD DE LIBREVILLE – La juxtaposition 210 (1966)

Germinal Tenas, A&R man at Vogue, was behind the ambitious Jean-Bernard de Libreville EP that he produced in 1968: a conceptual meeting of punk – before it existed – dandyism and surrealism. This visionary record, trashy, mad and eccentric, was adored by those in the music biz, but not by a public that remained autistic and conservative. The Jean-Bernard de Libreville record remains to this day one of the finest musical flying saucers to ever land in France.

Fleeing the war in Algeria, Chaib Bouri was five years old when he and his parents arrived at the Bel-Air public housing projects in Montreuil-sous-Bois (93), just east of Paris. For his 10th birthday, his mother gave him a guitar and, self-taught, he already began to compose a few quirky songs while listening to the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan. Five years later, Chaib went to audition at Vogue records. Christian Fechner and Germinal Tenas, the A&R men at the label, liked what they heard. Tenas, himself cutting an eccentric figure with a monkey on his shoulder, a flowered shirt and cigar, signed Chaib to Vogue with a contract to make four 45s.

Tenas dubbed him Jean-Bernard de Libreville – to be more chic – and quickly brought him into the studio to make his first record (1966).

Based on Chaib’s lyrics and music, Germinal experimented, letting his unbridled creativity go wild: tapes running backwards, cacophonous rhythms, odd, repetitive music that Germinal baptized “hyperno-music.” This record, unique in its genre, is truly an aberration compared to what was coming out at the time.

To complete this conceptual, avant-gardist disk, Germinal needed an individual as deranged as the music. Chaib was therefore to incarnate a completely fabricated character: an enigmatic dandy with a very sophisticated look (Victorian frock coat, ascot tie, silver-tipped cane, wearing sunglasses rain or shine).

Nothing was left to chance. The cover of the EP, with a photo by Michel Quennville, husband of cartoonist Claire Bretecher, further reinforced the mysterious aura of Jean-Bernard de Libreville. Appearing majestically arrogant, Chaib is smoking a cigar and holds a child on his lap.

When the record came out, Tenas’ colleagues unanimously applauded his audacity. Chaib appeared to have a bright future, and was booked to play at the Olympia, a top-rank concert hall.

Tenas orchestrated and staged a press conference to launch the EP amid much fanfare. It was obliged to be stupendous; the launch needed to be worthy of the character he had invented. Vogue organized an event that was practically a “happening.” Surrounded by bodyguards, Chaib arrived triumphantly at a nightclub on the Champs Élysée in a luxurious Jaguar. He jumped out amidst strident, blaring sirens and giant banners marked “Juxtaposition 210,” before an audience of dumbfounded journalists. Jean-Bernard was supposed to perform the “trashy dandy” act that he had adeptly prepared with Germinal. Unfortunately, 15-year-old Chaib became overwhelmed, lost his nerve, and Germinal’s little party ended in disaster. Jean-Bernard was paralysed by fear, unable to speak.

The prank turned into a nightmare, giving rise to a virulent shouting match between Germinal and Jean-Bernard. Exaspirated by Germinal’s manipulations and by being the object of his delusions, Jean-Bernard refused to honor his commitments. He refused to make any more 45s and to continue working with his mentor. The contract was rescinded, the Olympia date canceled, and Jean-Bernard was consigned to showbiz oblivion.

A few years later (1969), Christian Fechner, sacked by Vogue, had just set up his own label. Fechner searched for an artist to do a sophomoric, naughty disc, with the intention of riding the wave of indignation aroused by the release of “Je t’aime… moi non plus” from the Gainsbourg-Birkin duo. Jean-Bernard agreed to come up with this made-to-order album of lewd and bawdy songs. Accompanied for the occasion by the Haricots Rouges (red beans), the recording was quickly finished. Fechner was only moderately enthusiastic about the outcome of these recording sessions, sometimes lacking inspiration, often clumsy. He had just started working on movies with the Charlots (a group of musician-comics) and the project with Jean-Bernard became quite secondary. Fechner gradually lost interest in the record and it never saw the light of day, with the tapes remaining in Jean-Bernard’s custody.

A few years later, when Jean-Bernard was in a scrapyard looking for a part to repair his old Rover, he stumbled across Hilary Cus, a former Vogue employee who was now organizing concerts and tours in France for groups from the Caribbean. He had also just set up his own label, called Dayvis. Cus agreed to put out two 45s with four songs from the Fechner recording sessions. The two singles, “Allons y gaiement / Du Miles Davis” and “Sexo-phone / Les Pipes,” came out in a limited edition.

Soon afterward, Chaib abandoned his Jean-Bernard de Libreville pseudonym. Difficult times followed. Continuing as best he could, he played frequently in the Métro and put out a few records under different names (Cyril Savine, Chaib).

FATTY NAUTY – A tumba Part 2 (1968)

Bernard Paganotti, born in Oran, Algeria, got together with Christian Vander in 1967 to form the group Chinese, soon renamed Cruciferius Lebonz. In 1968, Paganotti released an EP on Barclay under the name “Fatty Nauty n’ Cruciferius Lobonz,” including the track “A Tumba Part 2” that appears on this compilation. They played a few dates opening for Ronnie Bird and David Alexandre Winter, but were not well received.

In 1967, Christian Vander left to form Magma. Bernard continued the group with François Bréant, Patrick Meru and Patrick Jean. Under the name Cruciferius, they recorded an album that remains one of the masterpieces of French progressive rock. The group broke up in the early 70s and Bernard joined his friend Vander in Magma. In September 1976, Bernard left Magma to form Weidorie.

His excellent playing made Bernard one of the most sought-after French bassists in the 80s. He recorded with Francis Cabrel, Johnny Halliday, Mylène Farmer and Vanessa Paradis, to name just a few.

Bruno Leys – Eve (1968)

You heard him first on WIZZZ Vol. 2 with the explosive “Maintenant je suis un voyou (Now I’m a hoodlum).” Here he is again, with this first class track, never before published.

But, let’s go back in time… In early 1967, Bruno was attending medical school in Paris. Driving back to the university with a friend, Bruno sang along nonchalantly with the songs on the radio. His friend was surprised to discover his lovely voice and encouraged him to audition for a group composed of friends from the university who were looking for a singer. Bruno was not selected for the group, but became friends with one of its members, Emmanuel Pairault.

Emmanuel had been studying economics, but decided to enter the music conservatory instead, to learn the drums and the use of the illustrious “ondes Martenot,” a primitive electronic musical instrument.

He composed a few solo numbers, remarkable for their use of that instrument. Looking for someone to write lyrics to go with his instrumental tracks, he asked Bruno to try a few. Bruno and Emmanuel thereby put together a small repertoire, with no ambition other than to have fun. Although the details are now forgotten, they worked hard to bring their song to the attention of Nicole Croisille (a singer and actress), who suggested sending the demo to her friend Norbert Saada, who headed a label called La Compagnie.

This unprecedented use of the ondes Martenot in a pop song attracted Saada, who offered to make a record. Emmanuel quickly assembled a small team to make the recording. The sessions took place at Dominique Blanc Francart’s studio on rue de la Gaîté in Paris, with Bernard Lubat on percussion, François Rabath on stand-up bass, Jimenez and Jean-Pierre Dariscuren playing guitar, Emmanuel Pairault and Sylvain Gaudelette on the ondes Martenot, not to mention Bruno on vocals. Four tracks were recorded for the EP: “Maintenant je suis un voyou,” “Eve,” “Hallucinations” and “Galaxie.”

With the sessions completed, Bruno left for his obligatory military service and thus lost control over things. Saada pressed a promotional 45 in an attempt to find a licensing deal in Canada, to no avail. A real collector’s item, this 45 includes “Maintenant je suis un voyou” and “Galaxie.”

Back from his military service, Bruno learned that Saada had gone out of business and sold his catalog, putting an end to any hope of issuing the EP (1969). “Eve” has never before appeared on a record.

NATO – Je t’apprendrai à faire l’amour (1969)

Nato was born in 1944 in Belgium to a middle-class family. His father was a relatively high-ranked government official. His mother was a devout Catholic and he received a very strict religious upbringing. He studied at the Collège de St Luc, a top Belgian fine arts university, and quickly discovered a passion for painting.

His first job after school was as a decorator for the Belgian national airline Sabena. But soon, this non-conformist, still unknown in the art world, felt stifled and quit the job to focus solely on his art, which developed in multiple media. Nato did a bit of everything: painting, performance art, sculpture, music and cinema. He acted in several feature films for his friend Christian Mesnil, including the mysterious “Psychedelissimo.”

Quickly, his painting became erotic and sex became central in his work. In 1968, Nato signed with the Riviera label and issued two explosive 45s simultaneously: “L’amour interdit par la loi (illegal love) / Je t’apprendrai à faire l’amour (I’ll teach you to make love)” and “Marijuana / Faire l’amour / Tu ne dis pas ça / Le grand voyage” (1969), all too provocative for commercial success.

Clearly hippie-minded and subversive, his songs are all odes to fornication, free love and artificial paradises, which obviously are not everyone’s cup of tea.

The records flopped and Nato returned to painting. He organized numerous exhibitions and happenings throughout Belgium.

In 1974, he recorded the album “Actuel Un” (Barclay) together with the Swedish group Lady Pain and moved to Paris with his wife and children. In the years that followed, Nato continued with a regular stream of artistic projects, including the conceptual albums “F.M Acoustic” and “Triple objet créatif de consommation auditive” (1982), which did not have any greater success. Both were also pretty demented, to put it kindly.