ENGLISH TEXT BELOW

ENGLISH TEXT BELOW

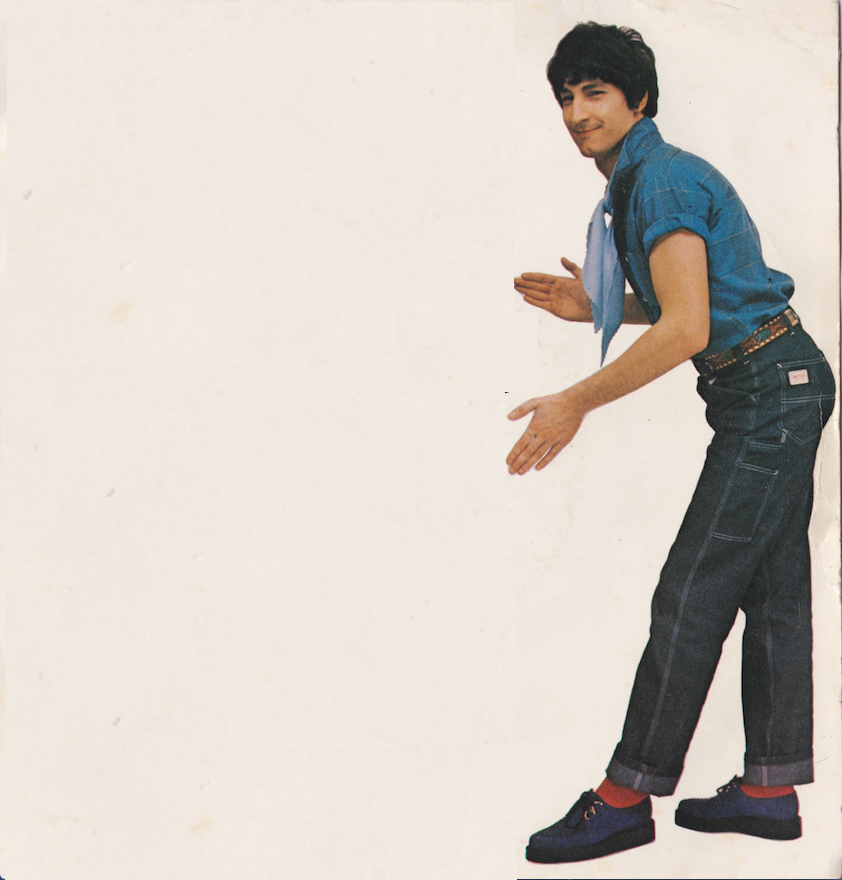

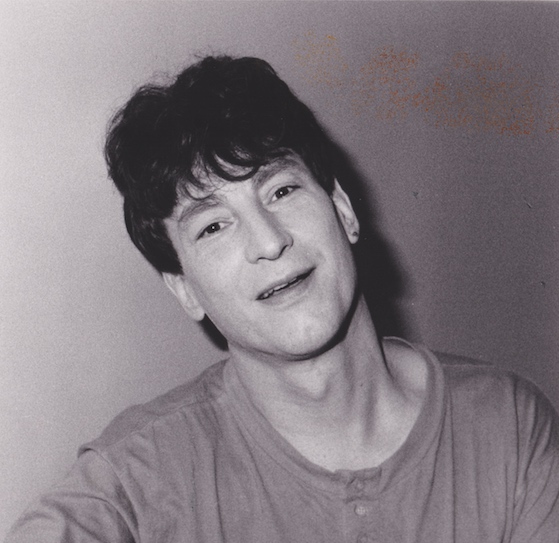

Parmi les héros de la disco hexagonale, Bernard Fèvre fut sous le nom de Black Devil le plus météorique et le plus singulier des auteurs compositeurs. Passé inaperçu à sa sortie en 1978, son premier album, Disco Club, est depuis devenu un disque incontournable qui a ouvert une porte sur la fantasque carrière de son auteur. Du rock au music-hall, de l’illustration sonore à la disco, de la pop au reggae, de la musique de film à la publicité, Bernard Fèvre s’est engagé dans toutes les directions pour mieux nous perdre dans le dédale d’une œuvre à nul autre pareil. L’un de ses meilleurs albums porte un titre programmatique : The Strange World Of Bernard Fèvre. Bienvenu dans une dimension inconnue.

Vous êtes né en 1946 à Asnières en proche banlieue parisienne. Quels sont vos souvenirs d’enfance ? Dans quel milieu avez-vous grandi ?Le premier souvenir ce sont les terrains vagues. On jouait dans la boue, on se marrait vachement. Asnières avait été épargné par la guerre. Mon père était ouvrier, il travaillait comme monteur levageur aux usines Chausson de Gennevilliers qui appartenaient à Renault et fabriquaient des moteurs pour les cars et les poids lourds. Mes grands-parents étaient vignerons en Bourgogne et du côté maternel faisaient du Cidre en Normandie. Ma mère était repasseuse blanchisseuse. C’était un milieu modeste, mais qui savait compter et qui ne buvait pas (rires). Je suis fils unique.

Comment votre intérêt pour la musique surgit dans ce contexte ?J’allais à la maternelle comme tous les enfants et dans le préau il y avait un piano sur lequel je jouais avec deux mains sans jamais rien avoir appris. Une institutrice s’est dit : ce n’est pas normal, il faut prévenir ses parents. Ma mère a trouvé un prof de piano. J’ai un peu appris à jouer, à lire la musique, mais au bout d’un moment ça m’a ennuyé car ce que je jouais était tellement moins bien que ce que j’entendais à la radio que je me suis dit que ça ne m’aidait pas et j’ai arrêté.

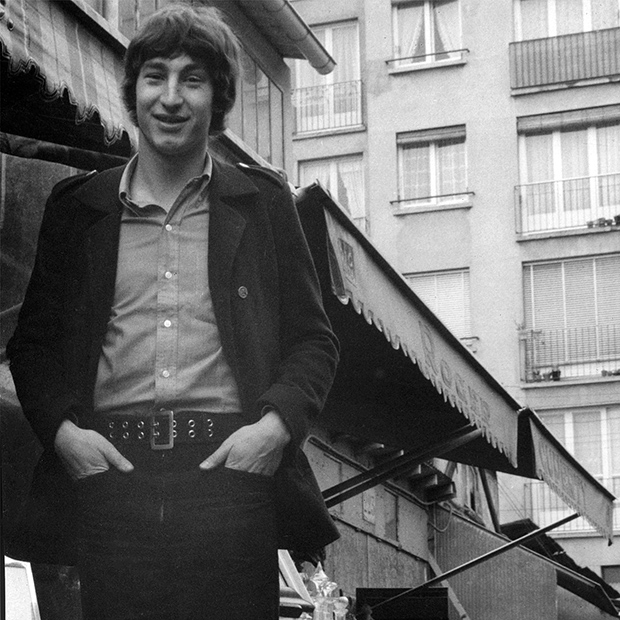

Qu’est-ce que vous écoutiez à la radio ?A l’origine ce que mes parents écoutaient : Gilbert Bécaud, Charles Aznavour, Edith Piaf, Les Roses blanches… Ce qui m’a donné envie de faire de la musique, c’est le rock’n roll et plus particulièrement les musiques noires américaines que je découvrais en écoutant Salut les copains, l’émission de radio la plus branchée de l’époque sur Europe 1 qui a gagné le cœur de tous les teenagers de cette époque et qui m’a donné envie de monter un groupe, les G men, avec Alain Paucard comme chanteur. Il avait réuni un bassiste, un batteur, un guitariste et un pianiste. On s’était rencontré dans un club où je jouais près de Saint Lazare. On répétait à Montmartre, c’était assez laborieux. Entre temps, j’avais un nouveau prof de piano plus moderne, dans un quartier plus chic d’Asnières, mais je ne voyais toujours pas l’intérêt de ces cours. A ce moment-là, je travaillais en usine. J’étais mauvais élève à l’école et on m’avait placé en technique. Au bout de trois ans d’usine, le fils du patron qui avait fait l’Algérie, vient me voir et me dit : « Tu t’emmerdes ? » je lui réponds : « Ouais », « Qu’est ce qui t’intéresse dans la vie ? » « Y’a que la musique qui me botte. » Il me dit alors : « Je connais un pianiste de bar dans un club près des Champs Élysées. Si tu veux je peux te le présenter. » Avec mon salaire d’ouvrier, je me suis alors payé des cours chez ce mec tous les samedis. Pour lui c’était glorieux d’avoir un fils d’ouvrier comme élève. Tout ce qui a pu me servir par la suite, je l’ai appris avec ce type qui avait une culture jazz. J’ai rencontré alors Les Vicomtes au cynodrome de Courbevoie, un groupe qui ne faisait que du rythme and blues, du Ray Charles. J’ai pris la place du pianiste quand il est parti faire son armée. On a fait quelques concerts dans des soirées, mais je continuais à travailler à l’usine jusqu’au jour où Les Vicomtes frappent à ma porte pour m’annoncer : « On a un contrat de quatre mois pour le casino de Deauville. » Je leur demande : « c’est payé combien » « 3700 francs» une paye de médecin, j’ai dit « banco ». Lorsque j’ai vu des riches perdre beaucoup d’argent au casino, je me suis dit qu’avec la musique je m’en sortirais toujours. Je ne suis jamais retourné à l’usine.

Après les Vicomtes, vous avez joué avec Les Francs Garçons…On répétait dans la même maison de jeunes à Courbevoie. J’aimais bien leur coté music-hall et j’ai intégré le groupe en tant qu’organiste. On a fait deux albums et des 45 tours, on travaillait beaucoup la scène, on a été le premier groupe à avoir une stéréo, une sono italienne. On est avant 68, je commençais à jouer sur des orgues électroniques, c’était très analogique mais avec de la technique, ça passait déjà par l’électricité. J’ai vraiment commencé à m’intéresser à la musique dite « électronique » à cause de Vangelis qui accompagnait Demis Roussos dans Aphrodite’s Child. Souvent avec les Franc Garçons, on se retrouvait en tournée dans les mêmes villes qu’eux. J’allais les voir et enfin j’entendais quelque chose de nouveau : fini les guitares et les batteries ! Mon oreille voyageait.

Après les Vicomtes, vous avez joué avec Les Francs Garçons…On répétait dans la même maison de jeunes à Courbevoie. J’aimais bien leur coté music-hall et j’ai intégré le groupe en tant qu’organiste. On a fait deux albums et des 45 tours, on travaillait beaucoup la scène, on a été le premier groupe à avoir une stéréo, une sono italienne. On est avant 68, je commençais à jouer sur des orgues électroniques, c’était très analogique mais avec de la technique, ça passait déjà par l’électricité. J’ai vraiment commencé à m’intéresser à la musique dite « électronique » à cause de Vangelis qui accompagnait Demis Roussos dans Aphrodite’s Child. Souvent avec les Franc Garçons, on se retrouvait en tournée dans les mêmes villes qu’eux. J’allais les voir et enfin j’entendais quelque chose de nouveau : fini les guitares et les batteries ! Mon oreille voyageait.

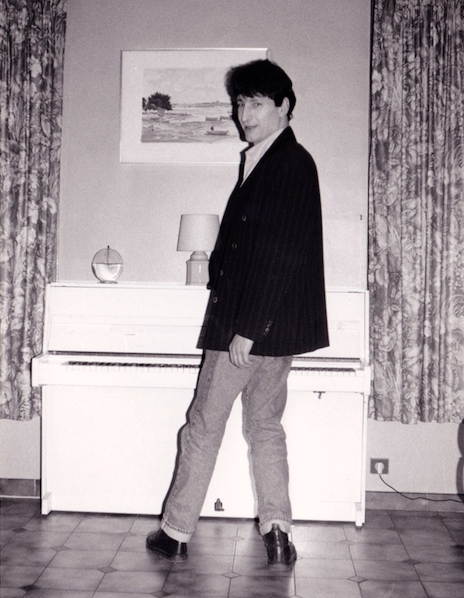

C’est un premier pas vers l’illustration sonore ?Oui, à partir du moment où je me suis intéressé à cette nouvelle musique, je me suis acheté du matériel pour construire un studio chez moi. Comme Jean Michel Jarre à la même époque, je me suis dit : puisqu’on n’arrive pas à passer la rampe, produisons notre propre musique. Je faisais circuler des cassettes dans les maisons de disque quand un jour je reçois un coup de fil d’Eddy Warner qui me propose de travailler pour lui, de lui fournir de la musique en me laissant une entière liberté, sans cahier des charges.

C’était donc un travail alimentaire mais aussi un espace de liberté ?Bien sûr car je rêve quand je fais de la musique. Je rêve que ça va être génial ! (Rires). En musique il n’y a pas de processus : tu peux partir d’une note, de ta voisine qui chantonne dans sa cuisine. Il y a une base, les fondations et après tu peux construire une maison jusqu’à la petite flute piccolo qui joue dans les hauteurs. Pour ça il faut connaitre l’orchestre classique, un truc que j’ai appris, j’entends ainsi souvent les erreurs d’orchestration.

Vous vous intéressiez à la science-fiction à cette époque ?Oui ce qui m’intéressait c’était la vision de l’avenir. Je suis un peu visionnaire vous savez : je sais depuis cinquante ans ce qui va arriver. Il suffit de regarder et d’écouter. On est dans la merde aujourd’hui car on vit dans un monde qui ne regarde pas et qui n’écoute pas.

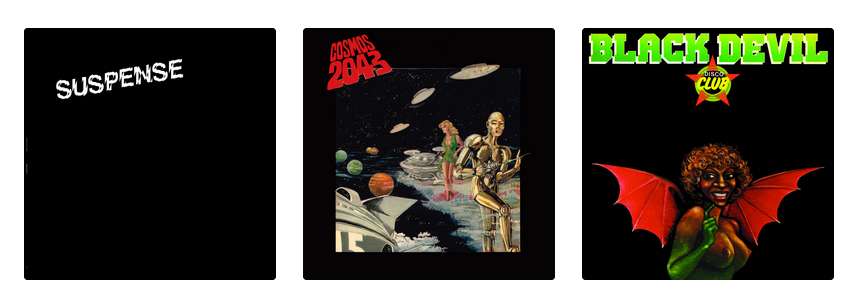

Vous côtoyiez d’autre compositeurs qui faisaient de l’illustration sonore ?Non, on ne se connaissait pas. L’éditeur faisait en sorte qu’on ne se rencontre pas pour ne pas penser en groupe. Certains comme Jacky Giordano ont même fait en sorte que je me fâche avec certains musiciens avec lesquels j’enregistrais pour préserver leur monopole. Je travaillais donc seul dans mon coin. Je fournissais des musiques sur lesquels ils mettaient un titre. Pour la pochette, j’avais plus ou moins mon mot à dire. C’était vraiment de l’artisanat.

Parallèlement à votre carrière d’illustrateur sonore, vous sortez également des 45 tours sous votre propre nom. L’idée c’était de décrocher un hit ?Oui mais ça n’allait pas très loin. Contrairement à la plupart des artistes qui réussissent, je n’ai jamais été complètement fan de moi. Donc je n’ai jamais essayé de gruger le public en piquant des notes faites par untel ou untel. Si je devais faire une émission sur le plagiat, j’aurais beaucoup à dire.

Parallèlement à votre carrière d’illustrateur sonore, vous sortez également des 45 tours sous votre propre nom. L’idée c’était de décrocher un hit ?Oui mais ça n’allait pas très loin. Contrairement à la plupart des artistes qui réussissent, je n’ai jamais été complètement fan de moi. Donc je n’ai jamais essayé de gruger le public en piquant des notes faites par untel ou untel. Si je devais faire une émission sur le plagiat, j’aurais beaucoup à dire.

En travaillant dans la pop musique, vous fréquentiez le showbizness de l’époque ? Que je détestais ! J’ai été directeur artistique chez Barclay, parce que Eddy Barclay avait aimé l’arrangement que j’avais fait, très avant gardiste pour l’époque, pour une chanson de Jean Louis Foulquier. Barclay m’a présenté des tas de gens, comme Léo Ferré avec qui j’ai diné, et m’a donné un bureau, mais je n’étais entouré que de baltringues. Le mec d’à côté passait son temps à appeler sa femme pour savoir si les chemises se vendaient bien dans son magasin. Ils n’en avaient rien à foutre de la musique !

C’est à partir de ce moment où vous travaillez pour la radio ?J’avais balancé des cassettes un peu surprenantes qui ont plu au directeur de la régie pub d’Europe 1. J’étais un peu un homme à tout faire, on m’appelait pour résoudre des problèmes spécifiques. Par exemple j’ai dû « secouer » l’antenne d’Europe 1 pendant 48 heures en produisant des effets dynamiques, des « tatatas » sur les génériques pour réveiller les auditeurs.

Comment est né Black Devil Disco Club ?Mon idée c’était de faire réfléchir les gens qui dansent, de les faire voyager ailleurs que dans leur quotidien. Le disco c’était un prétexte pour faire arriver plus facilement ma musique dans les oreilles des gens. En France quand tu arrives avec quelque chose de nouveau dans une maison de disque, la première réaction des directeurs artistiques c’est de dire : « je ne vois pas ». Et bien il faut apprendre à regarder. Beaucoup de morceaux qui ont cartonné ont été jeté au départ par les maisons de disque. La musique ce n’est pas leur métier.

L’arrivée du Disco c’était un peu la ruée vers l’or ?Oui, j’en ai profité pour faire écouter ce qu’il y a au-dessus en faisant écouter ce qu’il y a en dessous. La disco c’est ce qu’il y a en dessous : une simple base rythmique que j’ai fait dévier en rajoutant des percus africaines, mais aussi de la musique brésilienne et du reggae.

L’arrivée du Disco c’était un peu la ruée vers l’or ?Oui, j’en ai profité pour faire écouter ce qu’il y a au-dessus en faisant écouter ce qu’il y a en dessous. La disco c’est ce qu’il y a en dessous : une simple base rythmique que j’ai fait dévier en rajoutant des percus africaines, mais aussi de la musique brésilienne et du reggae.

Avec BDDC vous aviez l’ambition de faire un tube pour les boites ?Oui, j’aurai aimé, mais le BDDC a fait un tube trente ans après grâce aux anglais qui ont redécouvert le disque. J’allais beaucoup en boite à l’époque pour danser. On ne peut pas faire cette musique si l’on reste un bout de bois. Ce que j’aimais dans la disco, c’était la funk music. J’aimais moins la disco allemande que l’américaine.

Quel était le rôle de Jacky Giordano dans BDDC ?Je l’ai rencontré grâce à Alice Sapritch parce que j’ai participé à la réalisation d’un de ses albums. Je lui servais de coach vocal. Jacky Giordano était sur le coup. Il était sur tous les coups. Il me faisait marrer, on déconnait bien ensemble, son coté pied noir et mon côté ouvrier fonctionnaient bien. A l’époque, il travaillait pour les éditions de Pierre Bellemare et j’ai été lui faire écouter mes maquettes de BDDC. J’avais besoin de textes en anglais et il m’a aidé à les écrire en prenant bien sur une part sur le disque. Un reflex d’escroc. Il n’est que parolier sur ce disque, mais il a fini producteur des bandes car il était censé payer les séances de studio. Ce qu’il n’a jamais fait d’ailleurs.

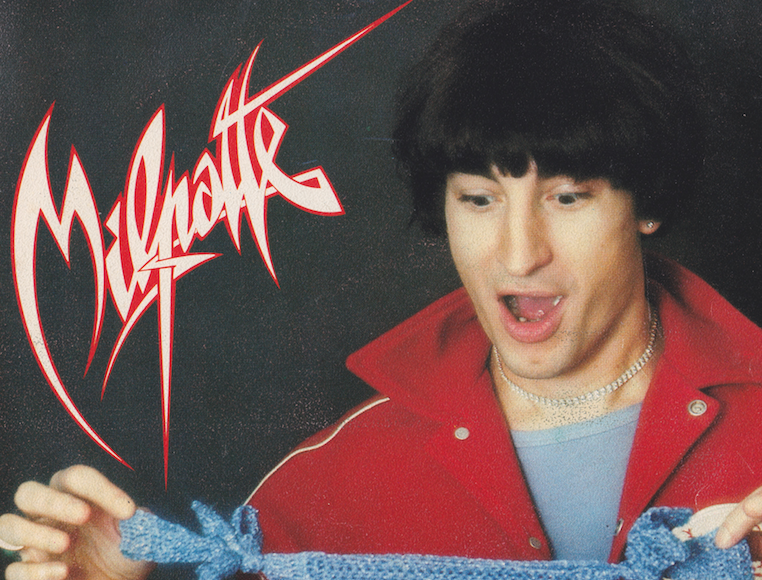

Vous avez fait un morceau reggae à cette époque.Oui c’était une idée de Jacky Giordano qui voulait profiter de la mode reggae. J’ai même fait une émission de Danielle Gilbert à la télévision avec un bonnet de rasta que ma femme m’avait tricoté et de fausses dreadlocks. J’étais accompagné d’un groupe d’antillais.

Au début des années 80 vous enregistrez des 45 tours sous le nom de Milpatte.C’était vraiment de la déconnade. Les musiciens ne se prenaient pas au sérieux à l’époque. La dérision c’est mon caractère. Le nom de Milpatte vient du moment où je faisais des musiques pour des courts métrages muets de la Gaumont au synthé et au piano dans l’esprit des années 30. Je regardais les films au studio de Joinville et ensuite je composais chez moi de mémoire. Mes doigts couraient alors sur les claviers comme un mille pattes.

Comment les anglais ont redécouvert votre musique ?Les premiers qui ont redécouvert un morceau à moi ce sont les Chemical Brothers qui ont samplé Cosmos 2043, un titre d’illustration sonore, sur leur titre Got Glint. En 1999 Aphex Twin a trouvé l’album de BDDC dans un car boot sale en Angleterre. Il l’a trouvé hyper innovant et l’a sorti en deux parties sur son label Rephlex. Quand j’ai vu que ça marchait, je me suis dit je vais pas en rester là et j’ai produit 28 years after chez moi. C’est à ce moment qu’un dealer de disque, Gwen Jamois (aka Iuke), m’a contacté pour savoir si j’avais des vieux trucs dans mes archives. Je lui ai dit que ça ne m’intéressait plus, que ce qui m’intéressait c’était demain. C’est comme ça que je lui ai fait écouter le nouveau BDDC. Il a trouvé ça monstrueux et m’a mis en contact avec Lo Recordings avec lesquels j’ai sorti six albums. Je travaille actuellement sur le septième.

///////////////////ENGLISH///////////////////

///////////////////ENGLISH///////////////////

Among the figureheads of French disco, Bernard Fèvre, better known as Black Devil, probably had the shortest-lived carreer but was the most brilliant and unique mind of them all. Although his first album Disco Club, released in 1978, went unnoticed at first, it has since become a must-have, a collector’s item which has led a lot of listeners to further investigate into his extensive work. From rock music to music hall, sound illustration to disco, pop to reggae, through film music and advertising, Bernard Fèvre has experimented with so many genres that it has been hard not to lose track. One of his best albums even has such an unambivalent title as The Strange World of Bernard Fèvre. Please make your way to a cosmic dimension, verging on the unknown.

You were born in 1946 in Asnières, on the outskirts of Paris. What do you remember from your childhood? Where and how did you grow up, what’s your background story?

One of the first memories I have is my hometown wastelands, we used to play in the mud and have so much fun. Asnières had been spared by the war. My father worked in labor as an assembler in Gennevilliers for the Chausson factory, which belonged to Renault and built engines for buses and trucks. My dad’s parents lived in Burgundy and worked as winemakers and my grandparents on my mother’s side made cider in Normandy. My mother was an ironer and a laundress. I grew up in a low-income household with a family who had accounting skills and didn’t drink (laughs). I’m an only child.

How did you become interested in music in such a context?

Like other children I went to kindergarten. There was a piano in the playground and I played it with both hands without having learned before. “This isn’t normal, we have to tell his parents,” one of the teachers said. My mother found a piano teacher. I learned to play a bit, to read music, but after a while I got bored because what I was playing wasn’t as good as what I would hear on the radio. I thought it wasn’t really helpful and I quit.

What were you listening to on the radio?

Originally, I listened to what my parents used to play such as Gilbert Bécaud, Charles Aznavour, Edith Piaf, Les Roses Blanches. But what really made me want to make music was rock’n’roll, and more particularly Afro-American music which I found out about through the Salut les copains radio show, the coolest one at the time, which broadcast on the Europe 1 radio station and took over all teenagers’ hearts back then. This is where I drew inspiration from to form a band, Les G Men, which featured Alain Paucard as the lead singer. He brought together a bassist, a drummer, a guitarist and a pianist. We had previously met in a club I used to play in near Saint Lazare. We had a rehearsing space in Montmartre, we were not that good. In the meantime, I got a new, more modern piano teacher who taught in a pricier neighborhood of Asnières. But I still couldn’t see the point of taking music lessons. At the time, I was working in a factory. I had failed in secondary school so I had to enroll in a technical studying programme. After spending three years working in the factory, the boss’s son came to me. He had fought the war in Algeria. “Are you bored?” “Yeah,” I replied. “What are you drawn to in life?” he asked, “The only thing I dig is music,” I said. “I know a bar pianist who works in a club near the Champs Élysées. I can introduce you to him if you wish.” I used my blue-collar wage to pay the guy, he would give me lessons every Saturday. He thought it was fantastic to have a worker’s son as a trainee. Everything useful in my life I learned from this man. He had a jazz culture. Then I met Les Vicomtes at the Cynodrome in Courbevoie, they played nothing but rhythm and blues and Ray Charles covers. I took over the pianist’s place when he left in order to do his military service. We performed a few shows at parties but I continued to work in the factory. That is until one day, Les Vicomtes knocked on my door. “We’ve got a four-month contract to play the Deauville casino,” they said. “How much does it pay?” I wondered. “3700 francs,” which amounted to a doctor’s salary. “Let’s do this!” I said. When I saw rich people losing tons of money at the casino, it became clear I would always get by with music. I never went back to the factory.

After Les Vicomtes, you played with Les Francs Garçons…

After Les Vicomtes, you played with Les Francs Garçons…

We used to rehearse in the same youth house as them in Courbevoie. I liked their music-hall side and I joined the band as their organist. We recorded two albums and some singles, we put a lot of effort into improving our stage performances. We were the first live band to ever have a stereo, an Italian sound system. This was before 1968, when I started playing electronic organs. It was very analog but required a lot of technique and already involved electricity. I really started getting interested in the so-called “electronic” music by listening to Vangelis, who played along with Demis Roussos in Aphrodite’s Child. We Francs Garçons would often find ourselves touring the same cities as them. I would go and see them, and through them I heard a new sound at last. No more guitars and drums! My ears travelled.

Was it a first step towards sound illustration?

It was. From the very moment I became interested in this new type of music, I bought myself some equipment to build a home studio. Around that time, Jean Michel Jarre was around and I thought the same as him. “Since it seems we can’t make it, we should produce our own music.” I was passing cassette tapes around to record companies when one day, I got a phone call from Eddy Warner who offered me to work for him. He asked me to supply him with music and he allowed me complete freedom on the matter, with no directions whatsoever.

So it was a day job, but also a space for freedom, wasn’t it?

Of course it was. When I make music I dream. I dream that it’s going to be great! (Laughs). There’s no real process to making music. You can start with a note, or with the lady next door singing in the kitchen. There’s a base to it, you have to come up with foundations and from there, you can build up a house. You can go so far as to eventually add the little piccolo flute playing the high notes. To achieve that you need knowledge of the classical orchestra – and it’s something I’ve learned about. Hence, I often hear orchestration mistakes.

Were you interested in science fiction by then?

I was. I was all about having a vision of the future. I’m a bit of a visionary, you see. It has been fifty years I have known about what is coming up. You just have to look and listen. We are in deep shit today because we live in a world where nobody ever looks nor listens.

Did you know any other composers who worked in sound illustration?

No, we had no idea about each other. The publisher made sure we never met, so that we wouldn’t consider ourselves as a specific group and think as such. They even orchestrated arguments with musicians I worked with, Jacky Giordano was one of them, in order to maintain their monopoly. I therefore worked on my own. I would provide the music and they would put a title to it. When it came to the cover art, I more or less had my say. We really operated on a craftmanship level.

Alongside your career as a sound illustrator, you also released singles under your own name. Were you hoping to have a hit?

I did indeed, but I always kept it low profile. Unlike most successful artists, I have never been a huge fan of myself. Therefore, I’ve never tried to fool the audience and steal other people’s notes. If I were invited to a show talking about plagiarism, I would have a lot to say.

When you worked in pop music, did you hang out with the showbusiness people?

I hated them! At some point I worked for the Barclay company as an artistic director. Eddy Barclay had quite liked the avant-garde way I had arranged a song by Jean Louis Foulquier – I had done something quite edgy for those times. So he introduced me to lots of people, such as Léo Ferré whom I had dinner with once. He also gave me an office, but I was surrounded by pricks there. The guy next door would spend his time calling his wife on the phone to inquire about how well shirts would sell in their store. They didn’t give a damn about music!

Did you start working for the radio at that time?

The director of the Europe 1 advertising department liked the tapes he came across. People would resort to me to solve all types of specific problems, I was a a bit of a handyman. Once, I was entrusted to spice up the Europe 1 broadcast. The point was to make sure listeners would stay alert and not fall asleep for as long as 48 hours and I managed to do so by producing dynamic sound effects and by adding various “tatatas” to the credits.

How did Black Devil Disco Club come about?

My idea was to bring thoughts to dancing people, to have them escape their everyday life. I used disco as a way to have my music enter people’s ears more easily. In France, when you offer a record company to listen to something new, the artistic director’s reaction is always to go “I can’t figure it out.”. Well, you have to learn to figure it out. A lot of songs that have become hits were rejected by record companies in the first place. Music has nothing to do with what they do.

Was the birth of Disco the promise of some sort of a gold rush?

Yes, I took advantage of it. By having people embrace what was below, I made people listen to the surface of the music, what was on top. Disco is what was underneath. It is a simple rhythmic base that I twisted by adding African percussions, as well as Brazilian music and reggae.

With BDDC, did you want to put out a banger and hope to have a hit in the clubs?

I would have loved to. BDDC actually made it to the charts but only thirty years later, when the English digged out the record from oblivion and gave it a second life. I used to go clubbing a lot back then, to dance. You can’t really make this kind of music and stay as still as a piece of wood. What I liked about disco was funk music. I liked German disco less than American disco.

What part did Jacky Giordano play in BDDC?

I met him through Alice Sapritch. I was involved in the making of one of her albums, I was her vocal coach. Jacky Giordano was part of it. He was always part of something. His pied-noir personality matched my working-class background and both worked well together, he made me laugh a lot, it was always good fun to be with him. He worked for Pierre Bellemare’s publishing company at the time and through him I could have them listen to my BDDC demos. When I needed to come up with English lyrics he helped me write them, then he was mentioned on the record and got paid of course. He acted like a crook, an old habit of his. On this record he was only a lyricist but he ended up being featured as producing the tapes – he was originally supposed to pay for studio sessions, but he never did!

You made a reggae song at the time.

I did, it was Jacky Giordano’s idea, as he wanted to capitalize on the reggae craze. I even got invited to a Danielle Gilbert TV show and wore fake dreadlocks as well as a rasta hat my wife had knitted for me. A West Indian backing band played along with me.

In the early 80’s, you recorded singles as Milpatte.*

We were joking. Musicians weren’t that full of themselves back then. I always make fun of everything, it’s part of my character. The name Milpatte comes from when I did music for Gaumont and I worked on silent short films. I played the synthesizer and the piano in the spirit of the 1930’s. I would watch the films in the Joinville studio and then compose from memory at home. My fingers would run over the keyboards like a centipede.

How did the British rediscover your music?

The first ones who brought back a song of mine to life were the Chemical Brothers, when they sampled a sound illustration track called “Cosmos 2043” on their album featuring the “Go Glint” song. Aphex Twin then picked up the BDDC album in a car boot sale in England, in 1999. He found it highly innovative and released it as a two-piece on his Rephlex label. When I saw people liked it, I told myself I shouldn’t just sit and watch, and I decided to produce 28 after at home. That’s when a record dealer named Gwen Jamois (aka Iuke), contacted me and asked if I had any other old stuff I wanted to dig out from my archives. I told him I wasn’t interested any more and that instead I looked forward to the future. That’s how I got him to listen to the new BDDC, which he thought was fantastic. He then put me in touch with the Lo Recordings people, with whom I’ve released six albums. I’m currently working on the seventh one.

*Milpatte refers to the phonetics for « mille-pattes », which is French for centipede.