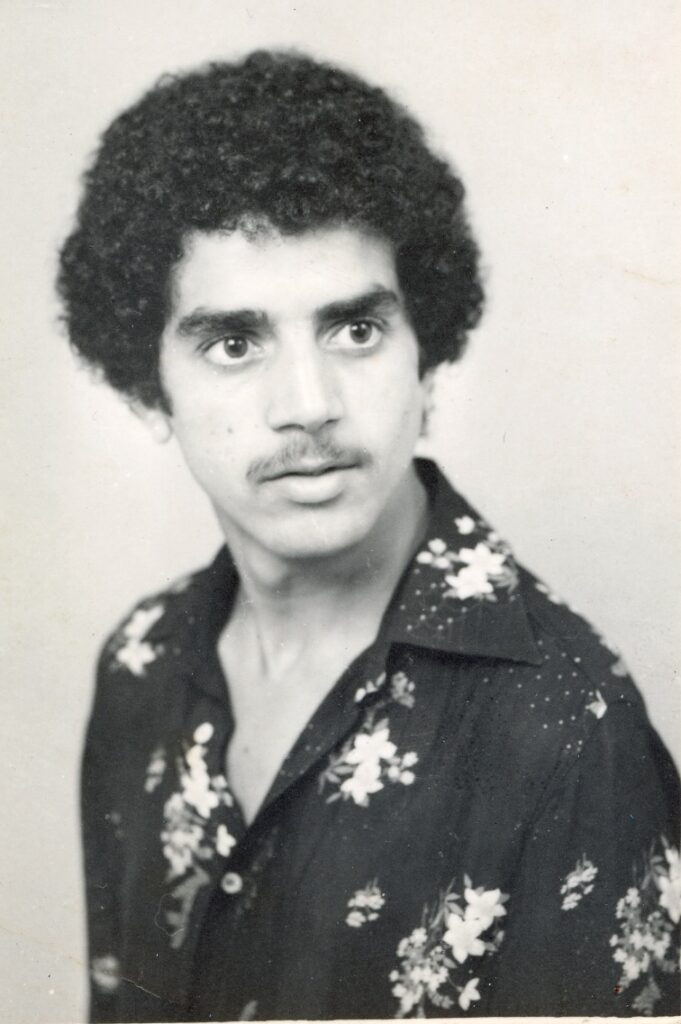

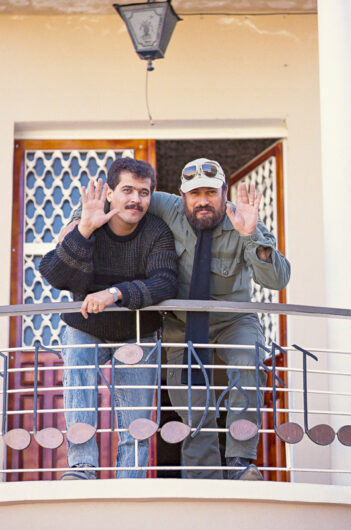

Houari Benchenet en studio (c)Photo Banjee

//////////////ENGLISH BELOW/////////////////

Raï Canal historique

Fouillant au plus profond des entrailles du raï, voilà une compilation qui évoque ses folles années et s’entend comme une cure de jouvence pour le genre oranais, version sulfureuse et souterraine… Très belle idée, donc, de puiser dans des cassettes introuvables pour confirmer que c’est dans les vieilles marmites oranaises que l’on trouve le bon raï. Il y a à peine cinquante ans, personne n’aurait parié un centime sur un genre condamné à tourner en rond en Oranie sa région d’origine, tapi au fond d’une de ces nombreuses discothèques tapissant la corniche oranaise. Dans ces lieux de vie underground, des chanteurs à orchestration minimaliste, faute d’espace, faisaient pleurer dans leur bière (ou rigoler dans leur Whisky…sec) un public toujours excité par des chansons transgressives, sonnant comme un défi à l’ordre moral et bien-pensant, sur fond de trompette, guitare électrique, accordéon et percussions diverses. Au cours de ces années pré et post-indépendance (1950-1970), le raï s’est urbanisé grâce à une génération qui a grandi entre bitume et béton, au son de la flûte traditionnelle, mais aussi et surtout à l’écoute du twist, de la variété française et du rock.

Ils se nommaient Boutaïba S’ghir, Messaoud Bellemou, Groupe El Azhar, Younès Benfissa ou Zergui et ils légueront aux chebs qui ont pris la suite leur bouquet de chants qui vont retrouver une seconde jeunesse. Oran, la capitale de l’Ouest algérien, en sera le centre névralgique.

Dominée à l’ouest par la montagne pelée de l’Aïdour, avec un pied sur une magnifique baie ouverte et un autre sur le profond ravin d’un oued depuis longtemps desséché et recouvert par des immeubles, Oran est certainement la ville la plus européenne d’Algérie. Et cela, en dépit de sa casbah, son sanctuaire édifié en 1793 sous le règne du Bey Othmane le borgne et dédié à Sidi El Houari, saint patron de la ville, souvent louangé dans la chanson raï et sa mosquée du Pacha, datant du XVIIIème siècle et bâtie à la mémoire des expulsés d’Espagne en 1492. C’est bien le moindre quand on sait qu’Oran, anciennement connue sous le nom berbère d’Ifri (la caverne), a été conçue en 903, sous le nom de Wahrane (les lions en berbère) par des marins andalous. Mais ce qui saute le plus aux yeux, ce sont les sites chrétiens, dont beaucoup ont été légués par les Espagnols qui ont occupé, dès le début du XVIIème, la cité pendant deux siècles. Citons l’église Saint-Louis, la cathédrale du Sacré Cœur ou la chapelle de la Vierge. Oran a la chance d’avoir la mer, ici d’un bleu plus intense qu’ailleurs, et des forêts de pins alentour et au-dessus, du côté de Santa Cruz. Bref, elle est riche d’influences hispaniques, andalouses, turques, arabo-berbères et françaises.

Ce cosmopolitisme a forgé son caractère le plus souvent enjoué. A Oran, on a toujours pris l’habitude de veiller et cela continue encore et encore. Les promenades sur le boulevard de l’ALN (ex-Front de mer) sont interminables et ne lassent pas les yeux braqués sur le port. Un peu plus tard, certains se dirigent vers le Théâtre de verdure, rebaptisé Cheb Hasni, du nom du créateur du raï love, assassiné le 29 septembre 1994. D’autres investissent les restaurants, surtout ceux qui excellent dans le poisson, avant d’aller se défouler sur la piste de danse d’un de ces nombreux clubs ayant pignon sur corniche. Les plus fameux ont pour nom « Le Florida » et « Le Dauphin » et leur nombre a augmenté ces dernières années, bien qu’Oran ait été, à un moment, touchée à son tour par des actes de violence. Les cabarets, où ont débuté Khaled, Cheb Mami, Fadéla et Sahraoui, Houari Benchenet ou Cheb Hindi demeurent l’habitat naturel du raï et constituent un incroyable vivier de talents.

Cheb Kader et Djamel Bel Yelles à Paris 1989 (c)Photo Banjee

Il ne faut pas croire cependant qu’Oran n’a pas souffert de sa réputation frivole et du mépris affiché à son égard par le reste de l’Algérie. Mais ses habitants se rassurent en moquant tous ces Algérois ou Constantinois qui débarquent le week-end sur les plages pour draguer les « petitates », ces filles dites faciles (on trouve même des étudiantes parmi elles), souvent en quête d’un beggar (littéralement : vacher, nouveau riche frimant dans les boîtes avec son portable et ses grosses liasses de billets). Quelques-uns viennent aussi pour approcher une de ces mariquitas (folles outrageusement maquillées), qui hantent le front de mer.

Le berceau géographique du raï, où Johnny Hallyday (avant lui, il y a eu Louis Armstrong et Joséphine Baker) avait donné un concert en 1966 au Casino, a toujours été un lieu d’encanaillement à portée de toutes les bourses. Le plaisir de la chair et de l’enivrement qui figure au programme de nombreuses chansons raï n’est pas une légende et à Oran, on se délecte toujours autant des amours illégitimes.

Avant de devenir un phénomène musical internationalisé, le raï a d’abord été l’expression d’un comportement social et une façon d’être. Il irrite, enthousiasme, séduit, mais ne laisse personne indifférent ! Surtout pas certains milieux intellectuels, politiques et religieux qui ont toujours clamé leur hostilité face à ce qu’ils considèrent comme un vulgaire et trivial sous-produit culturel. Présumé né en 1920 dans les plaines de l’Oranie, le mouvement a pris de l’ampleur dans les années 1940-1950, années de tous les défis, marquées par l’apparition des cheikhate (pluriel féminin de cheikha, équivalent au masculin cheikh), dont la regrettée Rimitti fut la figure emblématique, qui vaporiseront des airs bourrés d’allusions fines et coquines dans les bordels, les bastringues de seconde zone et les soirées privées qui prennent quelquefois des allures de saturnales. Le genre sera modernisé, dans les années 1960 et 1970, par des artistes comme Blaoui Houari, Ahmed Wahby, Messaoud Bellemou, Bouteldja ou Ahmed Saber. Cependant, côté arrangements et architecture musicale, il manquait de profondeur et de consistance. Un artiste majeur de la scène oranaise va le parer d’un habillage digne de son statut : Rachid Baba Ahmed, né le 20 août 1946 à Tlemcen, ville bourgeoise dépositaire d’un art andalou, le « gharnati », bien structuré et soigneux dans ses mélodies. Son père, très aisé matériellement l’était aussi au niveau artistique, lui qui jouait du « rebab » (violon traditionnel) au sein du meilleur orchestre de la ville dirigé par Larbi Bensari.

Rachid Baba et Salah Sahraoui au Studio Rally ( 1988) (c)Photo Banjee

Rachid en gardera un souvenir précieux mais, ado, il préférait le rock et le twist. Au début des années 1960, au moment où dans toute l’Algérie, des groupes au nom souvent américanisé mettent le feu sur les pistes de danse des complexes touristiques naissants, il s’achète une guitare et, secondé par son frère Fethi, il reproduit des standards sur des paroles chantées en arabe. Le succès pour les deux chevelus viendra en 1972 sur la foi d’un clip réalisé par la station télé d’Oran où on les voit chevaucher de grosses motos. Les deux frères sentant se lever le vent du raï, dans lequel ils ne s’identifiaient pas au départ, décident d’ouvrir un studio très sophistiqué, le Rallye, en référence à l’amour porté par Rachid aux courses automobiles, et prendra en mains les destinées de divers interprètes comme Fadéla, Khaled, Benchenet, Sahraoui ou Djalal. D’abord méfiants, les producteurs et éditeurs locaux finiront par multiplier les rendez-vous pour leurs poulains. Rachid, outre sa touche personnelle très convaincante, a mis au centre du jeu le synthé, enrichi par la présence de guitares acoustiques ou électriques et de boîtes à rythmes, et introduit, sous l’influence revendiquée de Jean-Michel Jarre, les délires électroniques. Le prodige des consoles sera enfin salué comme un génie des manettes et du concept studio. Il enchaîne les hits, les clips et les émissions de variétés à succès telles que “Top Raï” ou “Wach Raïkoum” (Quel est votre point de vue). Connu également pour ses tenues militaires, ses casquettes variées et ses excès de vitesse à bord de son 4×4, Rachid sera assassiné par balles, à Oran le 15 février. Fort heureusement pour lui, il aura eu le temps de voir triompher ses protégés et de mesurer sa contribution lorsque, au cours des années 1980, la bombe raï éclate véritablement et déferle, tel un impressionnant raz de marée, sur les consciences. Son armada de chanteurs, baptisés « cheb » (jeune), va bouleverser radicalement l’échiquier musical et ébranler sérieusement les fondements de la vieille aristocratie culturelle dont l’une des “tâches” les plus redoutables a été de dévaloriser les modes d’expression populaire ou d’essayer d’en interdire la manifestation.

« Vivre et laisser vivre », son crédo impatient, véhiculé par des centaines de milliers de cassettes a fait plus que séduire : il a conquis toute une jeunesse, majoritaire numériquement mais exclue socialement, coincée entre le désœuvrement, le chauvinisme des stades, le jargon patriotique des médias, le bar, la mosquée et un marché de loisirs pratiquement inexistant.

Au Cabaret Lahoune (c)Photo Banjee

Le succès du raï a été si foudroyant qu’en 1985 (présence au Festival de la jeunesse à Alger et tenue d’un premier festival raï à Oran), le pouvoir algérien s’empresse de le « nationaliser », tout en appelant à sa « normalisation » (entendez “javellisation” des paroles), et de le déclarer “partie intégrante du patrimoine national”. Près d’un an plus tard, le raï fait son entrée en France à travers deux festivals, l’un à Bobigny et à l’autre La Villette, qui rassemblent tous les grands noms, anciens comme nouveaux, de la chanson raï et attirent principalement un public de « blédards » (immigrés d’origine maghrébine)nostalgiques, plus quelques curieux. Ainsi, pendant quelque temps en France (au Maghreb, les marchands de cassettes sont dévalisés régulièrement), le raï ne suscitera pas d’engouement autre que médiatique (ou sociologique), même si quelques labels français oseront s’investir dans la reconnaissance de cette musique porteuse d’un nouvel élan au point de séduire et conquérir d’autres villes et régions algériennes et marocaines également. Plus tard, le style oranais connaîtra une reconnaissance internationale mais s’il gagne en technicité, il perd en feeling. Fort heureusement, le canal historique, celui décliné dans les tripots et les discothèques survivra au raï aseptisé, dans une ambiance sexe, alcool et raï ‘n roll.

Fin des années 1970, c’est Chaba Fadéla, née en 1962 et très vite remarquée par son rôle de garce dans le téléfilm « Le gaucher », qui ouvrira la première voix au raï électrique. Elle est alors âgée de 17 ans et elle bravera l’interdiction de se produire dans les cabarets. L’ancienne choriste de Boutaïba Sghir sera accompagnée par le fameux trompettiste Messaoud Bellemou. Dans les années 1990, en duo avec son mari d’alors, Mohamed Sahraoui, elle fera même carrière à l’étranger. Elle a fait partie de la génération formée par Khaled, Mami, Cheb Hindi ou Benchenet

Ce dernier est né le 25 mai 1960 à Oran au sein d’une famille aussi modeste que nombreuse. Influencé par Blaoui Houari, Ahmed Wahby, Ahmed Saber et Ben Zerga, les grands ténors de la chanson oranaise, annonciateurs du raï moderne, Benchenet a effectué ses premiers pas musicaux en 1975. L’ancien élève du Collège d’enseignement moyen Ibn Khaldoun, spécialiste dans le “civil” de la construction métallique, a tout d’abord testé ses qualités de musicien et d’interprète auprès de ses copains du quartier du Plateau, avant de se lancer à corps perdu dans l’animation des fêtes de mariages et de circoncisions. Ses attitudes scéniques et son jeu d’orgue subtil sont appréciés et lui font décrocher un bon nombre de contrats.

En 1977, il s’est fait remarqué au cours d’une soirée par Belkacem Bouteldja, dit “Kacimo”, la star absolue du pop-raï de l’époque, qui le laisse chanter de temps en temps à sa place. La voix claire et douce de Benchenet surprend agréablement l’auditoire et lui vaut d’être repéré par Abdelkader Cassidy, pionnier de la production, qui lui fait enregistrer sa première cassette qui obtiendra un vif succès. Propulsé ainsi sur les devants de la scène, Houari, qui ne s’est jamais encombré de la particule “cheb”, se met à écrire ses propres chansons, dont la plupart seront pillées par ses concurrents directs.

Ce qui le distingue de ses “coreligionnaires”, c’est sa touche romantique, sa manière de planter le décor et de redessiner la carte du tendre. Fin mélodiste et auteur de superbes balades, il est le créateur de l’école “rai love” que le regretté Cheb Hasni saura transformer en genre à part entière.

Son pote El Hindi, surnommé ainsi pour son amour immodéré des films bollywoodiens, a chanté au sein des scouts avant d’enregistrer une vingtaine de K7 au succès confidentiel avant de triompher avec « A moi la liberté ». Ils font parfois équipe avec le regretté Cheb Tahar, à la fois vocaliste et danseur extraordinaire, ce qui donnait à ses apparitions un côté spectaculaire. Tout comme dans le cas de Mohamed Sghir le bambin coaché par un père célèbre, Mohamed Belarbi, batteur et percussionniste de génie, est par ailleurs auteur de textes poétiques qu’il saura mettre en valeur grâce à la voix de falsetto de son fils.

Rachid Baba et Salah Sahraoui au Studio Rally ( 1988) (c)Photo Banjee

Cheb Hamouda, adepte du reggae, compte à son actif cinq enregistrements, dont le dernier remonte à 1991, sans avoir fait de plan de carrière, tout comme le rarissime Tchier Abdelghani. Leurs pendants féminins, à l’image de Chaba Amel, au timbre aussi entêtant qu’un parfum de jasmin et de la captivante Malika Meddah, excellente cavalière, comédienne de théâtre et ex-universitaire, ont eu un parcours plus chanceux. Et que dire des non-oranais : Cheb Djalal, natif de Sebdou (région de Tlemcen) au style mélangeant populaire marocain (introduction du luth) et raï façon Rachid et Fethi, ses producteurs initiaux issus de la même région ; Rostane Benali, arrangeur de Cheb Hasni ou Khaled, et ici du fan de ce dernier : Khaled Sghir (belle apparition dans le clip « Chaba » du roi du raï), né en 1965 à Alger ; et surtout le magnifique Nordine Staïfi (1956 – 1989), établi jusqu’à sa disparition à Chambéry, promoteur du « staïfi », sorte de compromis entre airs des Hauts-Plateaux de l’Est algérien, rythmes chaloupés des Aurès et groove oranais. Le Franco-marocain Cheb Kader, quant à lui, après un premier opus, « Awama » (L’ensorceleuse), d’où est extrait « Reggae-Raï », a connu un engouement international au cours des années 1990.

Aujourd’hui, comme en témoigne ce disque, voilà du raï qui fait encore et toujours aimer le raï.

Rabah Mezouane.

//////////////////////ENGLISH////////////////////////

Raï Historical Channel

Delving into the deepest recesses of raï, this compilation serves as a tribute to its roaring years, but also as a rejuvenation of the genre in its sulphurous, subterranean version. It seemed like a good idea to dig into nearly untraceable cassettes, thus confirming it’s in the oldest of Oranese pots that the very best of raï is to be found. Just 50 years ago, no one would have believed even a bit in a genre seemingly bound to forever turn round and round in its native Oran, laying low in one of its many coastal road clubs. In these underground venues, singers – backed up by a minimalist orchestration for lack of space – would move their audience to laughs and tears, sobbing in a beer or chuckling down (dry) whisky. Either way, the public would unfailingly be moved by their defying tunes, sounding like a challenge to the established, self-righteous order of things – complete with trumpets, electric guitars, accordions and an array of percussions. Through the pre and post-independence years, from 1950 to 1970, raï urbanised itself, with a generation growing up between asphalt and concrete to the sound of traditional flute, but also and mostly listening to twist, French variété and rock music. Their names were Boutaïba S’ghir, Messaoud Bellemou, Groupe El Azhar, Younès Benfissa or Zergui, and they passed on their collection of songs to the incoming “Chebs” –breathing a second youth into them. Oran, the capital of West-Algeria, will be at the heart of this rejuvenation.

Overshadowed to the West by the bare mountain of Aïdour, a foot set onto a beautiful bay and the other on a long dried out wadi, covered up with buildings since, Oran must be the most European of Algerian towns – regardless of its kasbah, its sanctuary built in 1793 under the reign of the Bey Mohammed ben Othman and devoted to Sidi El Houari, the city’s patron saint, and praised in many a raï song, and its Pacha 18th century mosque built in memory of the displaced Spaniards of 1492. The bare minimum, you could say, for a town formerly known as Ifri – or the cave, in Berber – and conceived in 903 under the name of Wahrane – the lions, again in Berber – by Andalusian seamen. The most notable, though, is its Christian legacy, mostly passed on by the Spanish who occupied the city for the best of two hundred years, from the beginning of the 12th century. To name a few, there’s Saint-Louis’ church, the Sacred Heart cathedral or the Virgin’s chapel. Oran is blessed with the sea, with its hue more intensely blue than elsewhere, and pine forests all around and above it, towards Sana Cruz. In short, it is rich with Hispanic, Andalusian, Turkish, Arab-Berber and French influences.

This cosmopolitanism is very much part of the city’s largely jovial nature. Staying up late is an enduring habit in Oran. Seaside walks on the ALN (former sea front) are never ending and the eyes riveted on the port, never tiring. Later still, some head for the open air theatre, renamed Cheb Hasni in honour of the creator of love raï, killed on September the 29th, 1994. Others take over restaurants – especially the ones with fish on the menu – before taking it all out on the dance floor of one of the many clubs dotted along the coastal road. The most famous ones are called “Le Florida” and “Le Dauphin”, and their number has been on the rise in the past years – even though Oran was, at one point, also hit by acts of violence. The clubs that have witnessed the beginnings of Khaled, Cheb Mami, Fadéla and Sahraoui, Houari Benchenet or Cheb Hindi remain the natural habitat of raï and a breeding ground for new talents.

Oran did however suffer from its frivolous reputation and the openly disdainful attitude of the rest of Algeria towards it. Its inhabitant easily reassure themselves though, mocking all of these Algerians and Constantinians who take over their city’s beaches to hit on “petitates”, these girls known to be promiscuous (sometimes even students) and often looking for a “beggar” (literally, a cowboy; a nouveau riche who likes showing off his smartphone and big wad of cash at the club). Some also come to Oran to chat up the “mariquitas” (queens wearing an outrageous amount of make-up) haunting the water front.

The birthplace of raï, where Johny Hallyday (and before him, Louis Armstrong and Josephine Baker) performed at the Casino in 1966, has always been known as the country’s affordable slumming spot. The pleasure of the flesh and inebriation recounted in many a raï song is no legend, and in Oran, illegitimate love affairs are still a great source of delight.

Houari Benchenet (c)Photo Banjee

Before becoming an international musical phenomenon, raï was first and foremost the expression of a social behaviour, of a way of being. It bothers, excites, seduces, but leaves no one indifferent! Especially particular intellectual, political and religious groups who have always declared their hostility towards what they consider to be no more than a vulgar and trivial cultural by-product. Presumably born in 1920 somewhere on the Oranese plains, the movement gains breadth in the 40s and 50s, years of majors challenges, which have seen the emergence of the “cheikhate” (feminine plural of “cheikha”, the equivalent of the masculine “cheikh), of which the late Rimitti was the emblem, propelling their innuendo-heavy melodies in the brothels, second-class dancehalls and private parties that could turn into near-Saturnalias. The genre was then modernised in the 60s and 70s, by artists such as Blaoui Houari, Ahmed Wahby, Messaoud Bellemou, Bouteldja or Ahmed Saber. However, the musical arrangements and architecture still lacked depth and consistency. A major artist of the Oranese scene, Rachid Baba Ahmed – born on the 20th of August 1946 in Tlemcen, a middle-class city custodian of the “gharnati”, a traditional art from Andalusia, with its well-structured and conscientious melodies – will finally give the genre the adornment it deserved. His father, well-off both in monetary terms but also artistically, played the “rebab” – traditional violin – with the city’s most renown orchestra, conducted by Larbi Bensari.

Rachid will keep a fond memory of his father’s music – though, as a teenager, he preferred rock and twist. In the early 60s, at a time when, all across Algeria, bands with (often) Americanised names would set the dance floors of the emerging tourist developments alight, he buys himself a guitar, and with his brother Fethi, covers standards with lyrics sung in Arabic. Success will come in 1972, with a video clip produced by Oran’s television station, in which the pair is seen riding big motorbikes. The brothers rightfully sensing raï’s wind rising – a genre they didn’t readily identify to – decide to open up a sophisticated studio, the Rallye, in reference to Rachid’s love for car racing. There, they take charge of the destiny of various singers, of which Fadéla, Khaled, Benchenet, Sahraoui or Djalal. Suspicious at first, local producers and editors entrust their protégés to the brothers, accumulating meetings at the studio. Rachid, apart from having a very convincing personal touch, gives a central focus to synth parts, enhanced by acoustic and electric guitars and drum machine. He introduces eccentric electronic parts, under the asserted influence of Jean-Michel Jarre. A virtuoso on the decks, he finally gains a reputation as a controller and studio concept genius. Hits, clips and famous variety television programs – such as “Top Rai” or “Wach Raïkoum” (What do you think?) – accumulate. Also known for dressing in military outfits, wearing varied hats and speeding with his 4×4, Rachid is shot dead in Oran on February the 15th. Luckily, he’ll have had time to witness his pupils’ triumph when raï truly explodes in the 80s, and, like a tidal wave, sweeps onto the public mind. His armada of singers, called “cheb” (young), is to radically transform the musical scene and shake up the foundations of the old cultural aristocracy, of which the most fearsome “tasks” had been to demean popular forms of expression and attempt to ban its manifestations.

“To live and let live” – his keen, impatient creed disseminated by hundreds of thousands of cassettes, did much more than seducing: it conquered a whole youth, predominant in number though excluded socially, baffled by idleness, stadium chauvinism and the media’s patriotic lingo, trapped between the bar, the mosque and a virtually inexistent leisure market.

Raï’s success was overwhelming, so much so that in 1985 – when it appeared at the Youth Festival in Alger and when Oran held its first raï festival – the Algerian authorities hastened to nationalise the genre, all the while calling for its “normalisation” (that is, the “purification” of its lyrics), and to declare it “an integral part of the national heritage”. About a year later, raï is introduced to France via two festivals, one in Bobigny and the other at La Villette. They brought together all of the big names of raï, old and new, and drew in a public mostly made out of nostalgic blédards (a French expression designating a person originating from the Maghreb), plus a handful of curious onlookers. In France, raï doesn’t stir much enthusiasm – if not in the media, or of a sociological kind. While in the Maghreb cassettes dealers are regularly ransacked, only a few French labels dare investing themselves in the recognition of a music bringing a new fresh wind, seducing and conquering other Algerian as well as Moroccan cities and regions. Later on, the Oranese style gains international appreciation and evolves technically – though more technique also means less feeling. Luckily though, the historical channel raï to be heard in the dives and discos survives its shinier cousin – sex, alcool and raï’n roll style.

In the late 70s, Chaba Fadéla, born in 1962 and noticed early on for her role in the TV film “Le gaucher” (the leftie), gives electric raï its first voice. She’s only 17 years old at the time, but ignores the ban prohibiting her from performing in cabarets. An ex-Boutaïba Sghir backup singer, she is supported by the famous trumpet player Messaoud Bellemou. In the 90s, she will even perform abroad, forming a duo with her then husband. She is part of the generation made up of Khaled, Mami, Cheb Hindi and Benchenet.

The latter was born in Oran, on the 25th of May 1960, to a large and modest family. Influenced by Blaoui Houari, Ahmed Wahby, Ahmed Saber and Ben Zerga, the leading figures of Oranese chanson and heralds of modern raï, Benchenet takes his first musical steps in 1975. A former student at the Ibn Khaldoun secondary school, a specialist in the civil part of metal construction, he first tested his skills as a singer and musician performing for his neighbourhood friends in the Plateau before making the great leap and performing for weddings and circumcision ceremonies. His charisma on stage and subtle way of playing the organ are well appreciated, landing him a fair number of gigs.

In 1977, he is spotted by Belkacem Bouteldja, known as “Kacimo”, an absolute raï-pop star at the time, who lets him sing in his place once in a while. Benchenet’s voice, soft and clear, is a pleasant surprise for the audience and has him noticed by Abdelkader Cassidy, a production pioneer who will get him to record his first cassette – a success. Houari, who never bothered with the particle “cheb”, is propelled to the scene’s forefront and starts writing his own songs – for the most part robbed by his direct competitors.

What sets him apart from his “coreligionists” is his romantic touch, his way of setting the scene and redefining tenderness. A fine melodist and the author of many outstanding ballads, he is the founder of “rai love” – turned into a genre of its own by the late Cheb Hasni.

His pal, nicknamed El Hindi due to his immoderate love for Bollywood movies, first sung with the boy scouts, then recorded a dozen of confidentially successful cassettes before triumphing with “A moi la liberté”. They will sometimes team up with the late Cheb Tahar, who was both a great singer and dancer – giving his representations a dramatic effect.

Like in the case of Mogamed Sghir, a kid coached by his famous father for his voice, Mogamed Belardi, a virtuoso drummer and percussionist, was also the author of poetic writings, which his son’s falsetto would bring out the best of.

Cheb Hamouda, a reggae fan, has five recordings to his credit, the last of which goes back to 1991 – he never planned for a career, just like Tchier Abdelghani and his extremely rare production. Their feminine counterparts – like Chaba Amel with her timbre as heady as the scent of jasmine, or the captivating Malika Meddah, combedian and ex-scholar – found more luck on their path. And what about the non-Oranese: Cheb Djala, born in Sebdou in the region of Tlemcen, with his style bringing together popular Moroccan music (introducing the lute) and raï, Rachid and Fethi style – his initial producers, hailing from the same region; Rostane Benali, arranger for Cheb Hasni and Khaled, or here for the latter’s fan: Khaled Sghir, with his great appearance in the king of raï’s clip “Chaba”, born in 1965 in Alger; and above all, the magnificent Nordine Staïfi (1956-1989), who lived in Chambéry until his death, promoter of “staïfi” – a sort of compromise between melodies from Eastern Algeria’s Highlands, swaying rhythms from Aurès and Oranese groove. Meanwhile, the Moroccan-French Cheb Khader tasted international success in the 90s after a first opus, “Awama” (the Sorceress), from which “Reggae-Raï” is taken.

And today, this compilation is a tribute to the kind of raï which, still and always, makes us love raï.

Rabah Mezouane.