Jean Pierre Decerf est né Neuilly en 1948 et a vécu à Paris jusqu’en 2003. Du début des années 70 jusqu’au milieu des années 80, cet autodidacte a composé une vingtaine d’albums d’illustrations sonores aux pochettes génériques dont les titres (Out of the way, Magical Ring, Keys of the Future, Pulsations, More and More…) sont autant d’appels à des voyages interstellaires. Ces disques expérimentaux, composés avec amour, humilité et des moyens rudimentaires, n’avaient alors d’autres fonctions que de servir les images des autres. En exhumant ces obscurités des oubliettes de l’histoire, Alexis Le Tan et Jess, en ont décidé autrement. En diggers éclairés, ils ont voulu rendre à Jean Pierre Decerf la place qu’il mérite : celle d’un innovateur dont les compositions rythmiques et synthétiques ont autant inspiré les hérauts de la French Touch (Air en tête) que certains rappers de la cote Est. Alors que l’été ne voulait pas s’en aller, il nous a reçu chez lui, dans un hameau isolé en Touraine où il vit en ermite. Parfois il croise Mick Jagger, qui a un château dans les environs, au supermarché du coin et la plupart du temps il parle en anglais avec ses voisins britanniques. Ce jour là, il a fait une exception pour évoquer son passé.

D’où vient votre intérêt pour la musique ?

Mes parents n’étaient pas musiciens mais gamin j’étais passionné par l’illustration musicale. Dans les années 50 mon père avait un projecteur de cinéma 9.5 car il faisait des films à droite et à gauche. Il était ingénieur du son mais sa passion c’était de filmer, de mettre en scène des films amateurs bâtis sur de petits scénarios. Ses films étaient muets et moi je m’amusais à y coller de la musique avec des moyens rudimentaires : je copiais de disques sur des bandes magnétiques en essayant de les synchroniser avec l’image. J’avais 12, 13 ans.

Vous avez appris un instrument ?

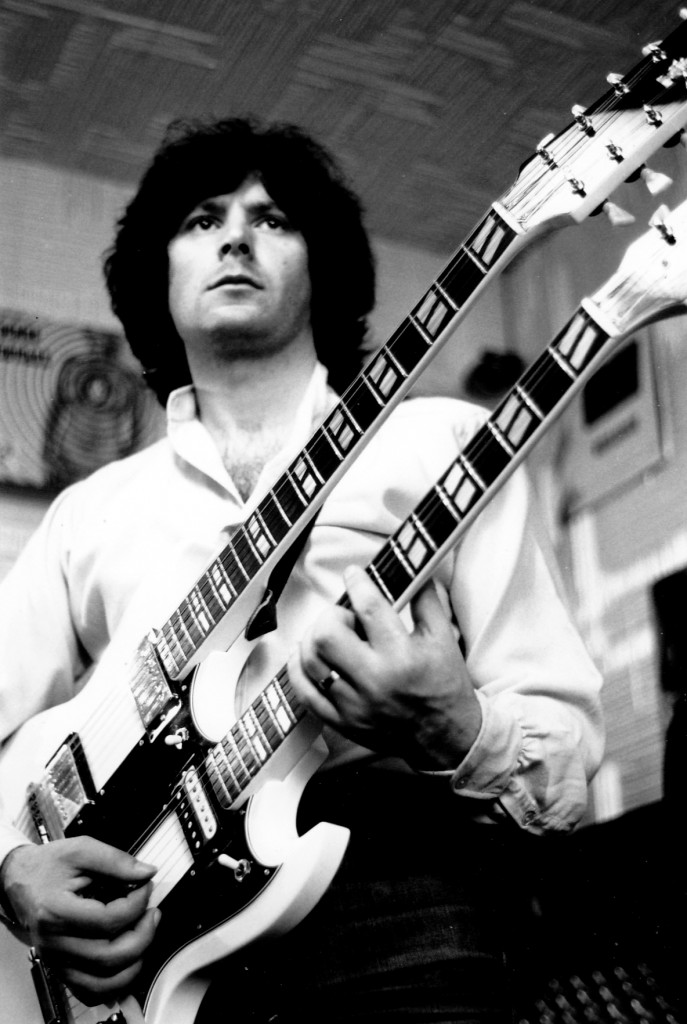

Ado, car c’était le début de la pop musique : les Beatles, les Stones, les Yardbirds etc… On a commencé a monter un groupe avec les copains de l’école vers 14, 15 ans qui s’appelait The Witchers. On faisait des repets et des concerts dans des salles de la banlieue parisienne comme le Centaure Club à Enghien. Je jouais de la guitare en autodidacte, j’avais le feu sacré mais j’avais quand même du mal, j’ai donc pris 6 mois de cours. On avait un peu de succès. On a fait le tremplin du Golf Drouot. On faisait des reprises comme la majorité des groupes de l’époque : Pretty Things, Them, Yardbirds, Action… Du rock Anglais plutôt pointu pour l’époque, les gens nous aimait bien car ils ne connaissaient pas notre répertoire.

Comment avez vous découvert ces groupes ?

Chez les disquaires parisiens, Lido Music, Symphonia, le Discobole de la gare Saint Lazare plus tard Givaudan vers 68, 69, une boutique d’enfer : des disques très chers mais les seuls à avoir des imports. C’était mon repère. J’y achetais du Grateful Dead, du Jefferson Airplane, du Big Brother, du 13th floor elevators… que l’on ne trouvait nulle part ailleurs.

Vous alliez également à des concerts ?

Oui tout le temps. Les Beatles à l’Olympia, j’y étais. La plupart des concerts des Stones. Mais aussi Move et des vieux rockers comme Chuck Berry ou Bo Diddley. Ensuite ça a été la Locomotive tous les samedi soirs. C’étaient des grosses stars comme les Who qui passaient là-bas : la Walker Brothers, les Pretty Things. C’était la boite référence avec le Golf Drouot qui était plus français. Il y avait le Bus Palladium aussi mais qui avait une réputation plus sulfureuse : ça trafiquait de la drogue, il y avait des bastons. La Loco, le clientèle était assez bcbg : cheveux long mais propre, bien s apé. Le style Beau Brummell à jabots

apé. Le style Beau Brummell à jabots

C’était votre look à l’époque ?

Non, moi j’avais le look Eric Clapton de Cream : cheveux courts, favoris et veste militaire.

Comment avez vous commencé dans l’illustration sonore?

Le groupe était un passe temps. La musique est arrivée par hasard. Je suis rentré à Pathé Cinéma en 72-73 grâce à mon père qui y travaillait. Je suivais sa trace sans enthousiasme en tant qu’assistant son. Mais il y avait un petit département d’illustration musicale et j’ai tanné mon père pour y entrer. Je m’occupais du catalogue, recevait les clients. Un jour le réalisateur Carlos Villardebo est arrivé à la recherche d’une sélection musicale. Sans trouver son bonheur. Il m’a alors dit « dis donc ton père m’a dit que tu jouais de la guitare, je veux juste de la guitare solo, tu pourrais me faire ça ? Dans le style Atahualpa Yupanqui… » Je connaissais pas du tout et j’ai couru acheter un disque. J’ai improvisé le lundi suivant dans un gros délire à la guitare encouragé par un Carlos extatique. C’était pour un film institutionnel intitulé Les trois vallées. Je trouvais ma musique horrible mais il a fait un montage son formidable. Ça a été un déclic. Je me suis ensuite lancé dans une musique électro acoustique – prémisses de la musique électronique – mais faite avec des objets, des bidons, des pots de peinture, des ressorts et de la guitare. C’était expérimental mais composé en examinant les sonorités au plus près. J’enregistrais tout avec un Revox et je m’amusais pas mal avec son système d’écho, je travaillais les répétitions comme dans la musique séquentielle. Je bossais alors avec Lawrence Whiffin, un compositeur australien de 20 ans mon aîné qui faisait de la musique contemporaine et qui m’a beaucoup encouragé.

Vous aviez l’impression de retrouver instinctivement ce que d’autres, notamment au GRM, faisaient à l’époque ?

Oui, Pierre Henri et Pierre Schaeffer avaient des bases, moi je n’en avais aucune. Mais j’ai arrêté cette veine là car elle ne me correspondait pas réellement à ce que j’aimais, à ma culture rock. J’ai fait quand même quelques titres dans ce style pour l’éditeur De Wolf qui ont servi d’illustration sonore mais n’ont pas été publiés.

Vous étiez nombreux a travailler dans l’illustration sonore ?

Non pas du tout. On pouvait se compter sur les doigts d’une main. La plupart c’étaient des gens de télévision : Bernard Gandrey-Rety, Betty Willemetz, Bernard de Ronseray et Dominique Paladille. Ils faisaient tout : le journal télévisé, les documentaires etc. C’était de la musique orchestrale principalement. Betty Willemetz, que j’ai bien connu, s’inspirait souvent de musiques de films. Le métier s’est ensuite élargi dans le privé avec des illustrateurs freelance.

Vous êtes ensuite contacté par la société Montparnasse 2000…

Oui ils avaient entendu parler de ce que je faisais. Ça les intéressait. Il voulaient que je fasse un disque pour eux. C’est à ce moment où j’ai arrêté la musique expérimentale et que j’ai acheté mon premier synthé, un Korg 700 monophonique, qui valait une fortune à l’époque, et une boite à rythme Yamaha, une des premières. J’avais également un 4 piste et un Revox pour le mastering.

Comment un disque naissait ? Vous composiez en fonction d’une commande précise ou vous rassembliez des morceaux existants ?

Ça dépendait des éditeurs en fait. Chez Montparnasse 2000 on me laissait faire ce que je voulais, chez Patchwork plus tard c’était plus précis. Des fois c’est pas mal de se raccrocher à quelque chose, d’avoir une direction comme dans les musiques originales pour les pubs et les documentaires. Mais je travaillais le plus souvent au feeling, je composais en général une vingtaine de titres et je sélectionnais au final les meilleurs. J’étais vraiment isolé, un peu égocentrique : je travaillais avec des musiciens mais je ne leur laissais pas vraiment la parole.

Il y a des compositeurs avec lesquels vous auriez aimé travailler en France à l’époque ?

François de Roubaix dont j’adorais la musique et à qui j’ai prêté un synthétiseur, un Elka Rhapsody, pour composer le thème principal de la Scoumoune. On s’est juste croisé et il a disparu trop vite. Mais ses musiques je les écoute toujours. Elles sont immortelles.

A cette époque vous sortez un disque sous le pseudo de William Gum-Boot intitulé Thèmes Médicaux avec Lawrence Whittin…

Ah en voilà de la musique expérimentale ! On a décidé de faire ce disque ensemble sans commanditaire pour s’amuser et Lawrence a trouvé que l’ambiance de nos expérimentations était scientifique, médicale. C’est comme ça que le thème général a surgi. On l’a ensuite proposé à Renaldo Cerri qu’on croisait pas mal à ce moment et qui l’a sorti sur son label Chicago 2000. Il nous a aidé a trouvé les titres comme Cancer ? Au secours ? Maison de repos, Transfusion Sanguine…

Vous preniez des drogues à l’époque ?

Non. J’ai fumé quelques joints comme tout le monde, mais c’est Phillip Morris qui a pris le dessus. Je ne dirais pas la même chose des gens avec qui je jouais. J’en ai fini des séances tout seul.

Vous vous intéressiez à la science fiction ?

Pas trop. Mais à l’astronomie oui. La science mais pas la fiction. Mon révélateur ça a été le Floyd. Celui de Syd Barret. Astronomy Domine, Interstellar Overdrive… tu n’as pas besoin de joints pour planer.

C’est ce qui vous amené a composer vos disques d’illustration dont la thématique tourne autour de l’espace ?

Absolument. Ça combiné avec mes livres d’astronomie.

Comment avez vous vu l’arrivée de musiciens comme Space ou Jean Michel Jarre ?

Ni chaud ni froid. A part Tangerine Dream qui étaient moins commerciaux. En fait la musique que je faisais à l’époque ce n’était pas celle que j’écoutais. J’étais dans le rock progressif, Yes, King Crimson, Asia et le jazz.

En 77, vous sortez Magical Ring que vous avez fait avec Gérard Zajd, c’est un disque particulier dans votre discographie…

En fait Renaldo Cerri voulait sortir mes morceaux dans le commerce, notamment ceux d’Univers Spatial Pop. J’étais contre car pour moi c’était de la musique d’illustration sonore. Il a insisté et j’ai fini accepter à une seule condition : que je puisse faire Open Air, un projet réellement destiné au commerce. Il a accepté. À l’époque j’enregistrais des bases chez moi sur quatre piste que je branchais ensuite sur le 24 pistes en studio et ensuite les musiciens radinaient. Mixage compris tout devait être réalisé en une demi journée. C’était intense. Des conditions limites car Renaldo n’avait pas beaucoup de budget. Mais pour Magical Ring on a pu mixer le morceau Light Flight en Angleterre à Olympic Sound Studio avec l’ingé-son Keith Grant qui avait enregistré les Beatles, les Who, Genesis etc… Il y avait l’idée de faire un coup. Derrière ses consoles, Keith Grant s’éclate, mets des sons à l’envers en intro, fait venir un chanteur black avec une voix pas possible, un batteur formidable. Il fait un mix de fou que j’adorais. Là, Je me suis dis : « Il va nous faire un tube. » Le soir il nous invite à dîner chez lui avec Renaldo et lui dit que le produit l’intéresse et qu’il veut le sortir en Angleterre chez Island. Mais Renaldo tirait la gueule car le mixage ne lui plaisait pas du tout. Il part néanmoins au Midem avec et revient en disant que ça ne plaisait pas du tout. Il décide de refaire le mixage en France en supprimant le travail de Grant. Ça ne me plaisait pas et je retourne en studio pour accoucher d’un clone entre les deux. On retourne avec ce mix sous le bras voir Keith Grant pour qu’il nous en fasse un nouveau. Il l’a fait du bout des doigts avant de nous foutre à la porte. J’étais furieux contre Renaldo, je l’ai laissé rentrer seul en France. Au final le disque est sorti trop tard : après Oxygène de Jarre et Magic Fly de Space.

Vous avez pu grâce à ce disque sortir Open Air, un projet personnel.

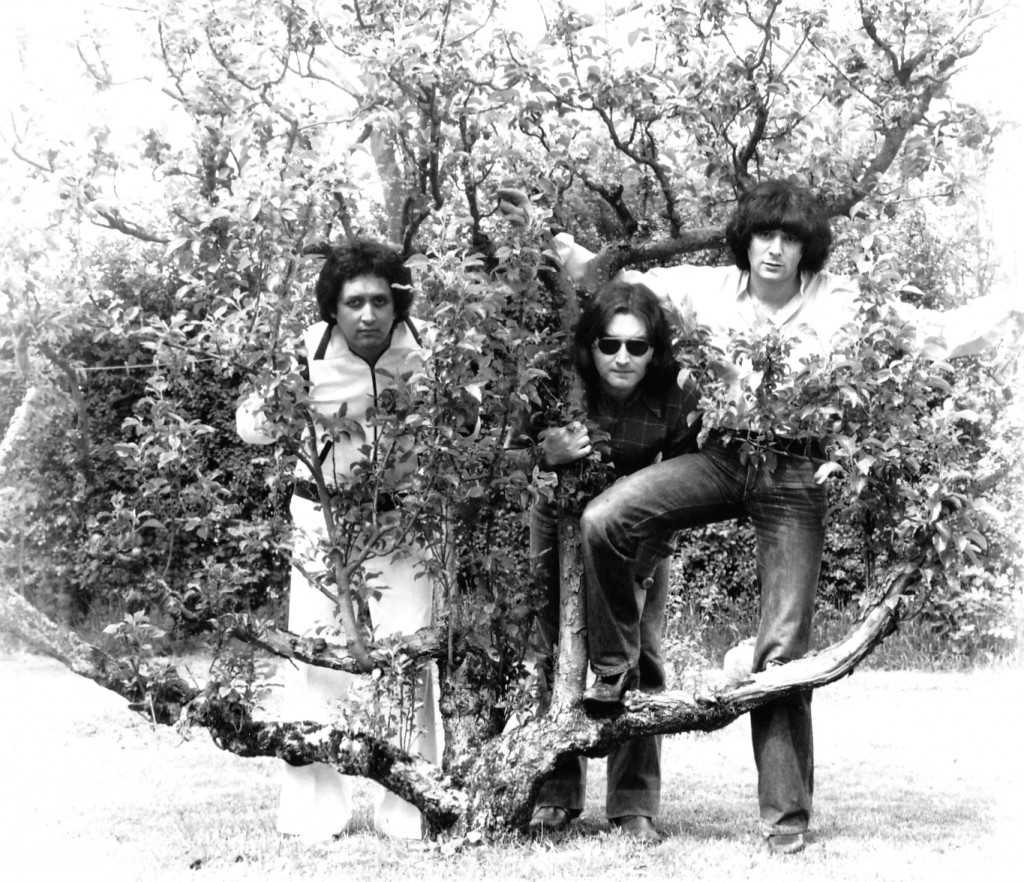

Open Air c’était mon bébé. Mon idée c’était de remonter un groupe, de donner des concerts, de sortir ensuite Open Air 2, 3… C’était les musiciens de Magical Ring principalement, Gerard Zajd, mon ami d’enfance à la guitare et Clarel Betsy au chant. Mon idée c’était de mélanger la musique space et le prog rock. Mais ça n’a pas marché. Autant sur Magical Ring on a bénéficié d’un peu de promotion et du titre More & more qui passait en rotation sur FIP -ce qui nous a permis de vendre 12000 exemplaires- autant sur Open Air on a rien eu. On en a vendu 850.

Pourquoi ne pas avoir fait de la Disco qui explosait à l’époque ?

On en a fait avec Gerard Zajd. Un projet qui s’appelait Manhattan. Mais en 1984. Autant on pu être précurseurs sur certaines choses, autant pour la disco on était trop en retard. On l’a produit nous même mais ça n’a pas été distribué.

Il y a un aspect assez dance dans votre musique.

Sans doute parce que je suis très attaché à la rythmique. J’ai travaillé avec d’excellents batteur, notamment Jean Marie Hauser qui est très précis, très carré. Je mélangeais aussi souvent boite à rythme et batteur, ce qui donnait de l’ampleur à la musique en soulignant son identité dance.

Après Open Air vous revenez à l’illustration sonore…

Oui j’étais un musicien professionnel et il fallait que je gagne de l’argent. J’ai enregistré Keys of The Future, Reincarnation, Sound Space… J’avais plus de moyens, du nouveau matériel. J’enchaîne alors sur une collaboration assez fructueuse avec le Label Patchwork avec lequel j’ai sorti les disques que je préfère dans mon répertoire, notamment Moments qui a un coté jazz fusion très prononcé. Les autres disques Patchwork restent dans le space rock mais sont différents de ceux réalisé pour Montparnasse Chicago ou Pema, ils sont musicalement plus structurés, pointus moins débridés, les sons et la mises en place sont plus intéressants. J’avais aussi plus de temps pour composer un album sur Patchwork, 6 à 8 mois alors qu’avec Renaldo j’étais dans une production trop intensive, parfois 3 ou 4 disques par an. A un moment il y a eu saturation, j’avais parfois l’impression de faire du remplissage. Avec Renaldo, on a quand même eu de très bon moments. Quand on s’est connu on était dans la dèche. C’est comme ça que se soudent les amitiés. Il aimait bien ce que je faisais et il a essayé de m’aider à la mesure de ses moyens, même si c’était difficile.

A quel moment vous avez constaté un nouvel intérêt pour votre musique ?

Grâce à Internet que j’ai installé ici en 2006. Mon neveu m’appelle un jour et me dit : « dis donc tonton tu es connu sur Internet, tu as vachement d’occurrences. » J’étais interloqué, j’ai vérifié et c’était vrai.

Vous faites toujours de la musique ?

J’attends de vendre ma maison et je vais partir m’installer dans le Gers où m’attends mon ami Gérard Zajd dans son studio. Ça va repartir !

Texte : CLOVIS GOUX

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Jean Pierre Decerf, born in Neuilly (a western suburb of Paris) in 1948, lived in Paris until 2003. From the early 70s to the mid-80s, this self-taught musician composed about twenty albums of production music* with generic cover art and titles (Out of the Way, Magical Ring, Keys of the Future, Pulsations, More and More, etc.) that evoke interstellar travel. These experimental discs, made with love, humility and rudimentary means, had no ambition other than to accompany other peoples’ images. By exhuming these obscurities from the dustbin of history, Alexis Le Tan and Jess have decided otherwise. Archaeologists with an agenda, they seek to give Jean Pierre Decerf the renown he deserves: that of an innovator whose rhythmic, synthetic compositions inspired the harbingers of the French Touch (Air comes to mind), not to mention some East Coast rappers. On a warm Indian summer day, we visited him at home in a remote village in Touraine (central France), where he lives as a hermit. Sometimes he runs into Mick Jagger, who has a castle nearby, at the local supermarket. Most of the time, he speaks English with his British neighbors. [Many small villages in rural France have numerous British residents, in particular retirees.] That day, he made an exception for us and discussed his past.

*Also called library music or stock music, it is generally composed and recorded, and then stocked as part of a commercial “music library,” with the objective of being sold as a soundtrack for cinema, television, commercials, etc., under a licensing model that differs from that for normal recordings.

How did you get interested in music?

My parents were not musicians, but when I was a kid, soundtracks fascinated me. In the 50s, my father had a 9.5 mm movie projector [an amateur format utilized in France] and he shot movies all the time. He was a sound engineer, but his passion was making movies. He would shoot amateur films based on short scenarios. His films were silent and I amused myself by adding music, using rudimentary methods: I copied records onto tape, trying to synchronize them with the images. I was 12 or 13 years old.

When did you learn an instrument?

Not until I was a teenager, inspired by the beginnings of pop music: the Beatles, the Stones, the Yardbirds, etc. I started a band called the Witchers with friends from school when I was 14 or 15 years old. We practiced and played concerts at venues in the Paris suburbs like the Centaur Club in Enghien. I had taught myself to play guitar. I was really motivated, but I couldn’t quite cut it, so I took 6 months of lessons. We had a bit of success. We competed in the battle of the bands (“tremplin”) at the Golf Drouot. We played covers like most bands of that era: English rock like the Pretty Things, Them, Yardbirds and the Action. This was rather sophisticated at the time; people liked us because they did not know those songs. [Strange as it may seem, many French teenagers listened mainly to French bands and only had a limited awareness of the current English groups.]

How did you find out about these bands?

At the Paris record stores: Lido Music, Symphonia and le Discobole at the Saint Lazare train station. Then, around 68 or 69, Givaudan, an incredible shop. Very expensive, but they were the only place to get imports. It was my home base. I bought records there that you couldn’t find anywhere else, like the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Big Brother and the Holding Company and the Thirteenth Floor Elevators.

You went to concerts too?

Yes, constantly. I saw the Beatles at the Olympia. Most of the Stones gigs. Not to mention the Move and old rockers like Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley. Also, I was at the Locomotive every Saturday night. Big stars played there, like the Who, the Walker Brothers, the Pretty Things. It was the most important club, along with the Golf Drouot, which was more French oriented. There was also the Bus Palladium, but it had a bad reputation. People sold drugs, there were big fights. The Loco’s clientele was rather preppy: hair worn long but clean, well-dressed. The Beau Brummels look, with ruffles.

Did you dress like that at the time?

No, my look was like Cream’s Eric Clapton: short hair, sideburns and a military jacket.

How did you get started in production music?

The group was just a hobby. My musical career happened by chance. I got a job at Pathé Cinéma [a huge cinema conglomerate that produces and distributes films, and also owns movie theatres] in 72 or 73 because my father was working there. I halfheartedly followed in his footsteps, working as an assistant soundman. But, there was a small production music department and I pestered my father to get me into it. I managed the catalog and dealt with clients. One day, the director Carlos Vilardebó arrived in search of a musical track. He didn’t find exactly what he was looking for, and he said to me, “Hey, your father told me you play guitar, I just want some unaccompanied guitar, can you do something for me? I want it to sound like Atahualpa Yupanqui…” I didn’t know Yupanqui from Adam, so I ran out to buy a disc. The next Monday, I improvised a guitar track in a big frenzy, encouraged by an ecstatic Carlos. It was for a corporate film called Les Trois vallées (The Three Valleys). I thought my music was horrible, but he did a fantastic job editing the sound. It suddenly clicked. I then dove into a kind of electro-acoustic music – a predecessor of electronic music, but made with objects, containers, paint cans, springs and the guitar. It was experimental, but composed by carefully contemplating the sonic elements. I recorded everything with a Revox [reel-to-reel tape machine] and I had a lot of fun with its echo system. I worked with repetition, like they do in minimal music. At the time, I was working with Lawrence Whiffin, an Australian composer 20 years my senior, who was creating contemporary music and gave me a lot of encouragement.

Do you have the impression to have instinctively found the same thing that others, in particular at GRM [Groupe de recherches musicales], were doing at the time?

Yes, Pierre Henry and Pierre Schaeffer had bases to start from, while I had none. But, I stopped working in that vein because it didn’t really correspond to what I love, to my personal rock ‘n’ roll culture. Just the same, I did a few tracks in this style for De Wolf, which served as production music, but have never been put out on records.

Were a lot of people making production music at the time?

Not at all. You could count us on the fingers of one hand. Most were TV people: Bernard Gandrey-Rety, Betty Willemetz, Bernard de Ronseray and Dominique Paladille. They did everything: the news show, documentaries, and so forth. It was mainly orchestral music. Betty Willemetz, whom I knew well, often took inspiration from film soundtracks. The profession then expanded into the private sector with freelancers. [At that time, French television was an exclusively public institution.]

Then, you were contacted by the company Montparnasse 2000…

Yes, they had heard about what I was doing, and they were interested. They wanted me to do a record for them. That’s when I stopped doing experimental music and bought my first synthesizer, a Korg 700 monophonic, which cost a fortune at the time, and one of the first Yamaha rhythm boxes. I also had a 4-track tape machine, and a Revox for mastering.

How does one of your records come into being? Do you compose [a whole record] in response to a specific order or do you put together various existing tracks?

In fact, that depends on the record company. At Montparnasse 2000, they let me do what I wanted; at Patchwork, later on, it was more clear-cut. Sometimes, it’s not a bad idea to have a guiding concept, a direction, as you have in original compositions for commercials and documentaries. But, most often I worked based on feeling. Generally, I composed around 20 tracks and then selected the best ones. I was really isolated, a bit egocentric: I worked with other musicians, but I do not really let them speak up.

Were there French composers with whom you would have liked to work back then?

François de Roubaix, whose music I adored. I lent him an Elka Rhapsody synthesizer to compose the main theme of La Scoumoune (The Excommunicating). We only crossed paths, unfortunately he passed away much too young. But I still listen to his music. It’s immortal.

Around that time, you released a record under the name of William Gum-Boot, entitled Thèmes Médicaux with Lawrence Whittin…

Ah, now that was experimental music! We decided to make this record together for fun, without any financial backing, and Lawrence considered the ambiance of our experiments to be scientific or medical. That’s how the general theme emerged. We were frequently running into Renaldo Cerri. We offered it to him and he released it on his Chicago 2000 label. He helped us come up with the titles, such as Cancer ? Au secours ? Maison de repos, Transfusion sanguine…

Did you take drugs back then?

No. I smoked a few joints like everybody else, but it’s Phillip Morris who dominated. I would not say the same for the people with whom I played. Sometimes I finished sessions alone.

Are you interested in science fiction?

Not particularly. However, astronomy interests me. It’s the science, but not the fiction. Pink Floyd was a real revelation for me. I’m talking about the Syd Barrett era. Astronomy Domine, Interstellar Overdrive… with songs like that, you don’t need joints to get high.

Is this what brought you to compose your production music records with themes revolving around space?

Absolutely. That, combined with my astronomy books.

How did you view the arrival of musicians like Space or Jean Michel Jarre?

I was totally indifferent. With the exception of Tangerine Dream, who were less commercial. Actually, the music I was making at the time was not what I was listening to. I was into progressive rock, Yes, King Crimson, Asia and jazz.

In 1977, you made Magical Ring with Gérard Zajd,. It’s a rather exceptional record in your discography…

In fact, Renaldo Cerri wanted to sell my compositions, in particular those from Univers Spatial Pop, as regular commercial disks. I was against it, because I considered it to be production music. He insisted, and I finally agreed, on one condition: that I could do Open Air, a project that was truly designed to be commercial. He agreed. At the time, I recorded the basic tracks on my 4-track machine, and then dubbed them to the 24-track machine in the studio. After that, the other musicians got into the act. Including the mix, everything had to be done in half a day. It was intense. We were pushed to the limit because Renaldo didn’t have a big budget. But, for Magical Ring we were able to mix the Light Flight track in England at Olympic Sound Studio with engineer Keith Grant, who had recorded the Beatles, the Who, Genesis, etc… We really wanted to do something special. At the mixing board, Keith Grant was having a blast, running sounds backwards for the intro, bringing in a black singer with an amazing voice, a superb drummer. He did an astounding mix, and I loved it. Then, I said to myself, “He’s going to make this into a hit for us.” In the evening, he invited us to dinner with Renaldo and told him that the product interested him, and he wanted to put it out in England on Island records. But, Renaldo got all sulky because he didn’t like the mix at all. Nevertheless, he took it to Midem [a French music trade show] and came back saying that no one liked it at all. He decided to remix it in France, and removed what Grant had done. I wasn’t happy with that, and I returned to the studio with the intention of creating a compromise between the two mixes. Armed with this tape, we went to see Keith Grant and asked him to do a new mix for us. He did a perfunctory job of it, and then sent us home. I was furious with Renaldo, and I let him return to France alone. In the end, the record came out too late: after Jarre’s Oxygène and Space’s Magic Fly.

Thanks to that disc, you were able to put out Open Air, a personal project.

Open Air was my baby. My idea was to put together a group to give concerts, and then put out Open Air 2, 3, etc. It was mainly the musicians from Magical Ring: Gerard Zajd, my childhood friend, on guitar, and Clarel Betsy singing. My idea was to mix space music and progressive rock, but it didn’t work. Magical Ring got a little promotion and the song More & more was in rotation on FIP [a Paris-based radio network], so we managed to sell 12,000 copies. However, Open Air was a flop. It sold 850 copies.

Why didn’t you get involved with the disco craze that was happening at that time?

I did, together with Gerard Zajd. Our project was called Manhattan. But, that was in 1984. While we could have been pioneers in certain styles, we missed the boat with disco. We produced the record ourselves but it was not distributed.

There is a danceable aspect to your music.

That’s undoubtedly because rhythm is very important to me. I worked with some excellent drummers, including Jean-Marie Hauser, who is very precise, perfectly rhythmic. Often, I combined a rhythm machine and a drummer, which made the music more forceful by emphasizing its danceable side.

After Open Air, you went back to doing production music…

Yes, I was a professional musician and I had to earn my living. I recorded Keys of Future, Reincarnation, Sound Space… I had more resources, new equipment. I followed up with a fairly successful collaboration with the Patchwork label, where I put out some of my most favorite discs I’ve ever done, including Moments, which has a very strong jazz fusion component. The other records on Patchwork remain in a rock idiom, but they’re unlike the ones on Montparnasse, Chicago or Pema. Musically, they are more structured and polished, more focused, the sounds and arrangements are more interesting. I also had more time to compose albums for Patchwork: 6-8 months, whereas with Renaldo, the pace was too intense, sometimes 3 or 4 discs per year. At a certain point, I reached my limit. Sometimes I felt like I was creating filler. But, I must say, I still had some very good times with Renaldo. When we met, we were flat broke. This is how close friendships are created. He really liked what I was doing and tried to help me to the best of his ability, even if it was difficult.

When did you realize that there was renewed interest in your music?

When I hooked up the Internet here in 2006. My nephew called me one day and said, “Wow, uncle, you’re all over the Internet, there are tons of Google hits.” I was blown away. I checked and it was true.

Are you still making music?

I’m waiting to sell my house. I’m going to move to the Gers [rural region in Southwest France], where my friend Gérard Zajd is waiting for me in his studio. I’m going to get back into it!

TExt : Clovis GOUX

Translation : Jon von Zelowitz