/////////////ENGLISH TEXT BELOW//////////

/////////////ENGLISH TEXT BELOW//////////

Lorsque les pilotes du vaisseau Space Oddities se sont attaqués à l’œuvre de Yan Tregger un problème s’est aussitôt posé à eux : par où commencer ? Par où terminer ? Par quelle paroi s’élancer pour gravir l’édifice ? Il aura fallu des années pour qu’Alexis Le-Tan et Jess réussissent à composer cette sélection qui rend compte de la profusion et de l’éclectisme de celui qui à 81 ans n’a pas rendu les armes et se définit toujours comme un « homme à tout faire ». Symphonies, illustration sonore, bandes originales de films, génériques télé, publicités, variété française, pop, disco, musiques électroniques, expérimentales ou de relaxation, Yan Tregger (né Edouard Scotto di Suoccio) aura embrassé tous les genres, les styles et les formats durant une carrière qui file des années 50 jusqu’à nos jours. Si ce stakhanoviste a multiplié les directions c’est qu’il avait une capacité innée à composer des mélodies. Elles sont le socle sur lequel il a bâti son iconoclaste production. Yan Tregger nous avait reçu, il y a dix ans déjà, dans le studio de son pavillon en banlieue parisienne. Face à ses consoles et à ses albums encadrés aux murs, il avait alors plongé dans les méandres d’une vie qui s’écrit comme une singulière partition.

Je suis né en 1940 en Algérie à Philippeville, c’était une ville côtière (aujourd’hui Skikda NDLA), la Nice de l’Algérie, mes parents étaient d’origine italienne. En Italie les gens étaient malheureux et ils ont fait comme font les migrants aujourd’hui. Il y a quand même eu un appel d’offre. Quand la France a commencé à coloniser l’Algérie, le gouvernement a fait venir des gens pour les faire travailler. Beaucoup d’Italiens mais aussi des maltais et des juifs qui étaient déjà implantés là-bas. Mon père était le patron de ce qu’on appelait une balancelle, un bateau qui faisait les côtes pour les livraisons de matériel. Ma mère était mère au foyer comme tous les italiens de l’époque. Je suis fils unique.

Vous avez des souvenirs liés à la musique durant votre enfance ?

Ma mère m’a mis au piano vers 9, 10 ans. Un jour j’ai rencontré des amis, il y avait une boîte et son orchestre qui s’appelait la philarmonique. Ils organisaient des après-midi le dimanche dans un kiosque sur une place. Comme il y avait des filles sympas à ces surprises parties je voulais y retourner. Mais l’on m’a dit que je devais appartenir à la philarmonique. Avec le piano je ne pouvais pas, je me suis donc mis à la trompette. J’ai monté mon orchestre là-bas, mais j’étais assez dissipé, je jouais la partition un octave au-dessus…

Quand est ce que vous êtes arrivé en France ?

Quand est ce que vous êtes arrivé en France ?

Avant la débâcle, dans les années 50. Je me suis marié et j’ai voulu venir en France pour travailler dans la musique. Avant j’étais greffier de tribunal. Quand on est arrivé en France j’ai commencé à travailler avec un orchestre.

Avant cela vous avez fait la guerre d’Indochine.

Oui. Comme je vivais dans une petite ville sans aucuns débouchés, moi je crevais là-dedans. Donc je me suis engagé pour entrer dans une école de radio, de transmission. C’était les balbutiements, on communiquait avec des radios à lampes. Ça m’intéressait beaucoup. Je me suis engagé pour trois ans et au bout de 18 mois on m’a envoyé en Indochine. J’avais 19 ans. On a pris un bateau à Marseille, le Pasteur, et on a mis un mois pour y arriver. Je me suis retrouvé avec les autres dans la calle. Ce n’était pas marrant. Il y avait en même temps les légionnaires, les tirailleurs marocains et sénégalais. Quand on a su que j’étais musicien, on ma tirer de là pour m’installer au premier étage. Je jouais le soir de la trompette pour les officiers. Ensuite j’étais à Saigon dans la transmission. A une soirée Jacques Chancel, qui était animateur à Radio France Asie, vient me voir et me propose de jouer dans son émission entre midi et deux heures de l’après-midi. J’arrive le mardi suivant après m’être fait remplacer à mon poste par un autre sous-officier et je lui demande : où est l’orchestre ? Et il me dit que je vais jouer tout seul. Quand je suis rentré deux soldats me sont tombé dessus et m’ont foutu en taule : désertion en temps de guerre. Un mois de prison où j’ai fait mes gammes à la trompette. Les autres détenus n’en pouvaient plus. On est venu me chercher pour jouer à une soirée donnée pour le général de Lattre de Tassigny. C’est comme ça que je suis sorti de prison. Puis j’ai été envoyé à Hanoï dans le Tonkin où j’ai continué à travailler dans la transmission. Là il y avait des talkies-walkies mais qui tombaient souvent en panne. Notre travail c’était de les réparer. Il y a eu un incident un jour, on est tombé dans une embuscade mais je préfère ne pas revenir là-dessus (silence).

Vous êtes ensuite rentré en Algérie ?

Oui où j’ai passé mon concours de greffier et me suis marié. On est parti en voyage de noce sur la côte d’Azur à Nice. Je voulais m’acheter une nouvelle trompette et je m’adresse à un certain Philippe connu de tous les musiciens du coin. Je choisis une trompette Yamaha, je paye en liquide 500 francs et la caissière me rend la monnaie plus mes 500 francs. Comme je suis revenu leur rendre leur argent nous sommes devenus amis et ils m’ont placé dans un orchestre où je remplaçais Aimé Marelli qui faisait toute la côte. C’est comme cela que j’ai rencontré plein de musiciens. Ensuite j’ai commencé à composer. Je le faisais avec une certaine facilité, j’ai plus de 2000 titres à la SACEM dont 700 enregistrés.

Vous montez à Paris au début des années 60 ?

Oui, je voulais chanter à l’époque. Au Petit conservatoire de Mireille, j’ai rencontré René Borg le réalisateur des Shadoks dont j’ai fait le générique d’entrée et de fin, mais cela ne m’a pas rapporté autant d’argent qu’on le croit. Les morceaux étaient trop courts.

Vous avez également dirigé à cette époque un orchestre symphonique pour une publicité Ariel dirigée par Jean-Jacques Annaud. Comment vous avez appris la direction d’orchestre ?

Sur le tas, j’étais très mauvais. C’est un véritable métier, une caste. On m’a dit il y a 40 musiciens, j’avais déjà fait plusieurs musiques de pub, j’y suis allé au culot. C’était facile car j’ai pris des musiciens de studio, mais plus tard lorsque j’ai enregistré avec l’orchestre de RTL, là c’était plus la même chose d’enregistrer une symphonie. Comme j’étais sympathique, ils se sont calés sur moi alors que d’ordinaire ils connaissent la partition et suivent les indications du chef en direct. Un chef d’orchestre m’a alors conseillé d’avoir deux paires d’oreilles, une pour la lecture de sa musique et l’autre pour l’écoute : c’est très, très difficile. Je n’étais pas sûr de moi, mais j’étais sûr de la musique. Ça m’a aidé.

Parallèlement vous sortiez également des 45 tours sous votre nom. Comment êtes-vous arrivé à l’illustration sonore ? Vous étiez peu nombreux à cette époque…

Parallèlement vous sortiez également des 45 tours sous votre nom. Comment êtes-vous arrivé à l’illustration sonore ? Vous étiez peu nombreux à cette époque…

La forme d’illustration sonore que je faisais était toujours basée sur les mélodies. Au début je faisais des chansons que je mettais en musique. Au lieu d’avoir des paroles c’était arrangé pour des orchestres. J’étais directeur des programmes dans une société qui s’appelait Mood Media, ça a été une source d’écoute musicale énorme. A l’époque il y avait une ambiance formidable entre les éditions et les musiciens, c’était très facile de faire écouter ses morceaux, il suffisait de décrocher son téléphone pour prendre rendez-vous avec les éditeurs. Les disques d’illustration sonores c’étaient des commandes qu’on me passait.

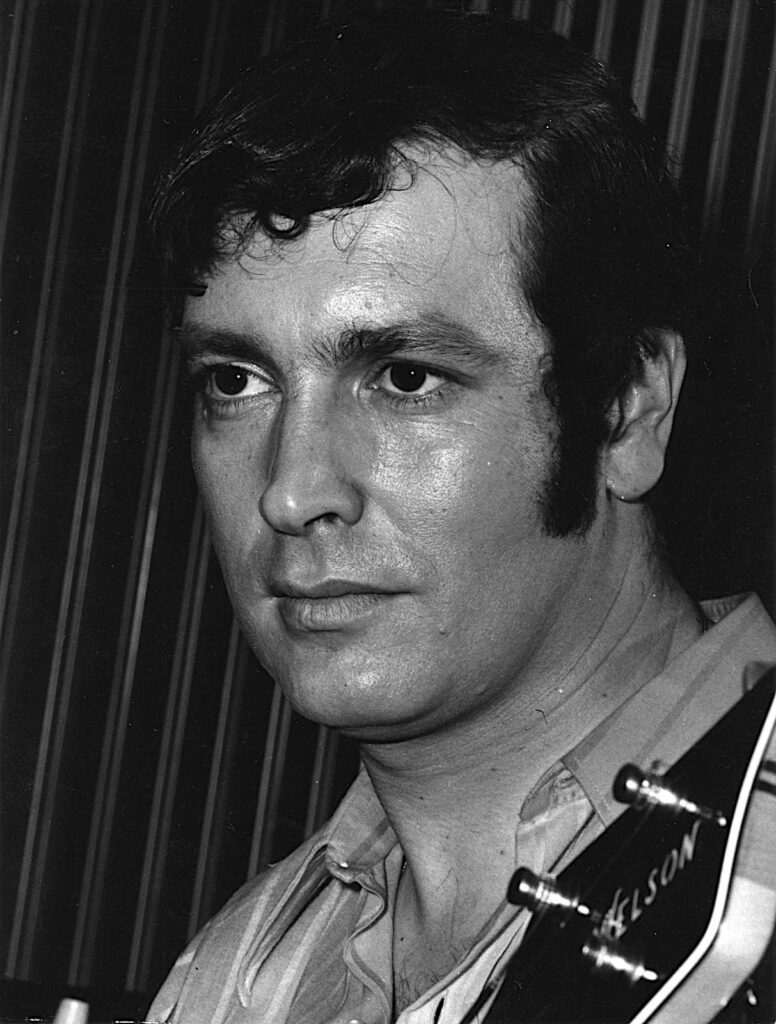

Vous prenez alors le pseudonyme de Yan Tregger.

Oui parce qu’un nom français pour ce style de musique ça ne servait à rien. Comme ça on croyait qu’il s’agissait d’un américain et ça m’a permis de distinguer ma carrière de chanteur de celle de compositeur d’illustration sonore. Dans les années 70 je faisais de tout : j’étais trompettiste dans des orchestres, j’étais compositeur de chansons et je faisais de l’illustration sonore. J’enregistrais à bras raccourcis. Les groupes m’appelaient « le compositeur fou » car je dirigeais tout le temps même quand j’étais un simple musicien.

On vous passait des commandes précises ou c’est vous qui ameniez les orientations artistiques ?

Non c’est moi qui proposais : je disais je vais mettre cinq musiciens à la rythmique, six violons, dix cuivres et puis on y va.

Vous écoutiez quoi à l’époque ?

Les Rolling Stones, T. Rex, Chicago, Isaac Hayes et plein d’autres choses. J’écoutais tout parce que je réalisais les disques d’illustration comme s’il s’agissait de disques du commerce à la mode. C’était peut-être une erreur mais c’est ce qui donne leurs couleurs à ces disques. Ils avaient une certaine qualité, ce n’était pas de la musique au mètre. J’ai toujours voulu faire mieux. Comme je composais rapidement et que je faisais les programmes de Mood Media qui devait prendre des marchés, le patron m’a demandé si je pouvais faire mille titres (rires). Mais on est quand même parti sur un programme d’enregistrement où pendant un an je n’ai pas cessé d’enregistrer ce qu’on peut considérer comme de la musique au mètre. Mais cela m’a permis de faire d’autres disques destinés au commerce qui étaient plus ambitieux.

Vous connaissiez les autres compositeurs d’illustration sonore ?

Oui. Il y avait une dizaine de compositeurs sur ce marché, mais c’étaient les bons.

Jacky Giordano on a travaillé ensemble, c’était un grand copain. Il est mort malheureusement. Il était très productif, un musicien de talent, très ouvert mais il s’est engagé dans un truc, des embrouilles à la sécurité sociale. Ça l’a détruit alors que c’était un pianiste et un compositeur hors pair. On a notamment fait Schifters ensemble. C’étaient principalement des improvisations écrites : vous faites un thème sur partition, un canevas avec des accords sur lesquels les musiciens pouvaient improviser.

Vous travailliez pour énormément de labels…

Vous travailliez pour énormément de labels…

Oui. Je n’ai eu de contrat qu’avec Barclay. Je ne voulais pas. Les labels sortaient les disques et les droits me revenaient via la SACEM, il n’y avait pas de problème là-dessus car la plupart des disques marchaient bien : on les entendait en radio et en télévision, c’était le travail des éditeurs. Par exemple à Montparnasse 2000, le patron il avait ses contacts dans ce monde-là qu’il retrouvait dans sa boite de nuit où il leur donnait ses disques.

C’était lucratif pour vous ?

Quand vous faites la musique de Sacrée soirée ou des Shadoks ça vous rapporte évidemment de l’argent.

Ce qui est étonnant c’est la variété de votre inspiration : du jazz rock, du psychédélisme, du funk, des morceaux à la limite de l’expérimental… d’où vient cet éclectisme ?

Sans doute des musiques de films car dans ce domaine vous devez savoir tout faire. Je suis devenu « l’homme à tout faire » (rires). C’est l’un des grands plaisirs de la musique.

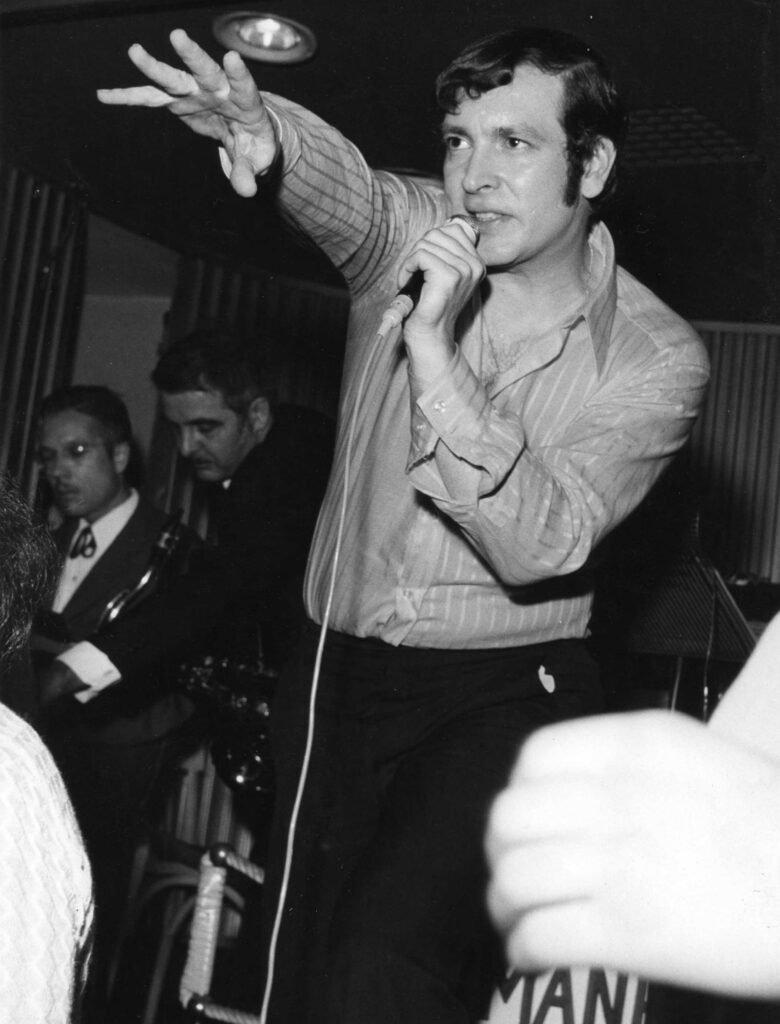

L’arrivée de la disco semble avoir changé votre carrière, comme l’avez-vous découverte ?

J’ai été l’un des premiers compositeurs disco en France, j’étais dans un studio avec des musiciens qui me disent « toi qui fais de la musique baston, on a un client qui cherche quelqu’un. » Je rencontre le bonhomme qui me dit : « il y a un truc qui s’amène, si vous êtes capable d’en faire ça m’intéresse. Ça s’appelle la disco… » Comme j’étais très branché musique funk, je me suis lancé pour aboutir à M.B.T. Soul dont le titre « The Chase » fait 16 ou 17 minutes. Le disque sort chez Polygram. Dans la même maison il y avait Cerrone qui sort une semaine avant moi. A l’époque on fait 100000 disques, classé au billboard canadien… Vous voyez « Love in C minor » de Cerrone ? C’est la même chose que

« Chase » et pourtant nous ne nous somme pas copié. C’était le style disco… Le succès est souvent dû à la chance et à l’opiniâtreté.

Vous avez également fait de la musique synthétique à tendance spatiale…

Oui, To The Land Of No Return avec un ARP, j’étais hyper branché sur les nouveaux instruments qui sortaient. Mais ce ne sont pas les instruments qui m’inspiraient, j’avais une idée et je cherchais les sons et donc les instruments qui collaient à cette idée.

Comment sont nées les trois œuvres symphoniques qui vous avez réalisé pour la radio ?

J’avais fait la musique d’un ballet avec un écrivain qui s’appelait Gérard Mourgue. C’est lui qui m’a envoyé chez Radio France à qui j’ai présenté un projet qu’ils ont accepté. C’est ainsi que je me suis retrouvé à diriger un orchestre de 40 musiciens. Gérard Mourgue c’était un poète, j’ai sélectionné certain de ses textes sur un album que j’ai fait, Les Grands Poètes, où l’on retrouve également des poèmes inédits de Jacques Prévert et d’Aragon.

Vous avez enregistré des musiques de films érotiques…

Oui avec le réalisateur Gérard Kikoïne, un des pionniers du genre. J’ai fait l’Amour à la bouche et ensuite deux musiques de films américains. Mais la musique de film c’était trop compliqué.

On retrouve d’ailleurs des thèmes de l’Amour à la bouche sur un disque étrange : Hotel Montparnasse Park…

Oui, j’avais été voir le directeur de cet hôtel et je lui ai vendu l’idée d’un disque sur son établissement. On a fait un tirage de 1000 pour 12000 francs, c’était bien payé. Puis après je me suis attaqué au Concorde La Fayette.

Vous n’avez jamais eu envie de faire partie d’un groupe ?

Non ce n’était pas mon truc, j’ai fait partie d’orchestres, c’est un investissement différent. Un groupe il ne fallait faire que ça. Ça ne correspondait pas à mon caractère. De la même manière je ne voulais pas m’investir dans un seul style.

Avant votre série d’album de relaxation pour Nature et Découverte vous écoutiez de la musique new age ?

Avant votre série d’album de relaxation pour Nature et Découverte vous écoutiez de la musique new age ?

Avec ce disque qui a cartonné, j’ai crée mon style. La musique new age est sans mélodie alors que ce que je propose est basé sur des mélodies. C’est toute la différence. Le disque Nature sorti en 94 a été le premier disque de relaxation. J’avais rencontré un musicien qui jouait de la flûte de pan et je me suis dit « tiens c’est sympa » (rires), j’ai donc fait une rythmique disco avec de la flute de pan. Je le fais écouter à un mec qui me dit : « c’est génial enlève toute la rythmique », (rires) « et tu me fais un album avec ça. » J’ai donc refait toute la base. Derrière la planéité, il y a donc du punch mais on ne l’entend plus. Résultat : on a vendu 120000 disques en quatre ans. Et je peux vous dire qu’il y a encore de la place et des idées.

Clovis Goux

//////////////////ENGLISH /////////////////

As soon as the pilots of the Space Oddities endeavour decided to tackle Yan Tregger’s oeuvre, a major problem surfaced: where to begin? And where to end? Upon which side should one launch into the ascension of this body of work? It will have taken Alexis Le-Tan and Jess years to put up this selection, capturing the profusion and eclecticism of Tregger who, at 81 years old, has yet to lay down the arms and still defines himself as a “jack of all trades”. Symphonies, library music, movie soundtracks, TV credits, advertisement, French variété, pop, disco, electronic, experimental or relaxation music, Yan Tregger (born Edouard Scotto di Suoccio) took up all genres, styles and formats through a career spanning from the end of the 50s to this day. How the Stakhanovist successfully went down so many different routes can be explained by his innate talent for composing melodies; they are the very basis on which his iconoclastic production was built. Ten years ago already, Yan Tregger had welcomed us in the studio of his Parisian suburb pavilion. There, sat in front of his machines and albums framed on the wall, he had delved into the midst of a life writing itself like would a rather unusual musical score.

I was born in Algeria in 1940, in a coastal town – Algeria’s Nice, Philippeville, (today Skikda – author’s note) , to parents of Italian descent. People were unhappy in Italy and did as migrants do today. Still, there was some tendering. When France started colonising Algeria, the government brought in people to constitute a work force: many Italians, but also some Maltese and Jews who were already established there. My father managed a balancelle, a dinghy which would deliver materials along the coast. My mother was a housewife, just like any Italian back then. I am an only child.

Where any of your childhood memories linked to music?

My mother had me learn the piano when I was 9 or 10. One day I met some friends, there was this club and its orchestra called the philarmonique, and they’d organise Sunday afternoon events in a kiosk on a square. Some nice girls would show up at these surprise parties, so I wanted to go back – but I was told I had to be part of the philarmonique. With the piano I couldn’t, so I took up the trumpet. That’s where I started my orchestra, but I wasn’t too focused, I’d play the score an octave too high…

When did you get to France?

Before the French debacle, in the 50s. I got married and wanted to come to France to work in music. Before that I was a court clerk. When we arrived I started working with an orchestra.

Before that you went to war in Indochina.

Before that you went to war in Indochina.

Yes. I worked in a small town, without any prospects – I was suffocating. So I enlisted to get a training in radio, in transmission. It was in its infancy, we were using tube radios. I was very keen. I enlisted for three years and after 18 months I was sent to Indochina. I was 19. We got on a boat in Marseille, the Pasteur, and it took us a month to get there. I ended up with all the others, in the hold. That was no fun. The hold gathered at once the troopers, the Senegalese and Moroccan infantry men. When it got known I was a musician I was taken out of there and moved onto the first floor. In the evening, I’d play trumpet for the officers. Then I was in Saigon, in transmission. There was an evening event once and Jacques Chancel, who was a host on Radio France Asia, came to see me and proposed I’d play in his show, from midday to two in the afternoon. I went the next Tuesday, my post filled-in by another non-commissioned officer, and I asked where the orchestra was. He told me I’d be playing alone. When I got back, two soldiers jumped me and sent me to jail for desertion in wartime. I spent a month in prison playing my scales on the trumpet – the other inmates couldn’t stand it anymore. They came to get me at one point, to play for a night in the general Lattre de Tassigny’s honour. That’s how I got out of prison. Then I was sent to Hanoi in the Tonkin where I kept working in transmission. They had walkie-talkies which would often break down, and our job was to repair them. One day there was an incident, but I’d rather not talk about it (silence).

Then you returned to Algeria?

Yes, I sat the court clerk exams and got married. We spent our honeymoon on the French Riviera, in Nice. I wanted to buy a new trumpet so I spoke to this Philippe guy who was known by all of the local musicians. I chose a Yamaha and paid 500 francs cash. The cashier gave me back my change, plus my 500 francs. I came back when I realised there had been a mistake, so we became friends and they had me replace Aimé Marelli in an orchestra that played along the coast. That’s how I met a whole lot of musicians. Then I started composing. I did that with a certain ease, I have more than 2000 entries at the SACEM (the French Society of Authors, Composers and Publishers of Music), 700 of which have been recorded.

And you went up to Paris at the beginning of the 60s?

Yes, back then I wanted to sing. I met René Borg, the director of Les Shadoks, on the TV program Le Petit Conservatoire de Mireille – it landed me doing the opening and closing credits, but I didn’t earn as much money as you’d think; the tracks were too short.

At the time you also conducted a symphonic orchestra for an Ariel commercial, directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud. How did you learn to conduct an orchestra?

On the fly; and I was really bad. It’s a real vocation, a career of its own. I was told there were 40 musicians and I had already done a lot of music for commercials – so I gathered the nerves and went for it. It was easy because I chose studio musicians, but later I recorded a symphony with the RTL’s orchestra – and that wasn’t the same thing at all. I was being nice, so they set their pace to mine, while usually they know the score by heart and follow the director’s indications. A conductor suggested I should have two sets of ears, one for reading music and the other for listening – which is real difficult. I didn’t trust myself, but I trusted the music and that helped me.

In parallel you were releasing 7 inches under your name. How did you end up doing library music? There weren’t many of you in that field back then…

The kind of library I did was always based on melodies. I started by composing songs I’d set to music. Instead of having lyrics, they’d be arranged for orchestras. I was the program director of a company called Mood Media and I’d listen to an enormous amount of music. There was a great atmosphere between publishers and musicians back then and so it was really easy to have someone listen to your tracks: you’d just have to pick up the phone and set an appointment with the publishers. The library records were commissioned by clients.

That’s when you chose the nickname Yan Tregger.

Yes, a French name for that kind of music was useless. That alias made people think I was American, and it helped making the distinction between my career as a singer and that as a library composer. In the 70s I did a bit of everything: I played the trumpet in orchestras, composed songs and made library music. I’d record in a frenzy. The bands called me “the mad composer” because I’d always be conducting, even when I was there just to be a musician.

Were your commissions precise or were you the one setting the artistic orientation?

No, I’d make a proposition. I’d say: “I’ll have five musicians on the rhythmical parts, six on the violins, ten on the brass…” and go for it.

What were you listening to at the time?

The Rolling Stones, T. Rex, Chicago, Isaac Hayes and so many other things. I’d listen to everything because I made the library records like they were fashionable commercial records. They had a quality to them, it wasn’t just stock music. I have always wanted to do better. As I was quick at composing and did Mood Media’s programming to take market shares, the boss asked if I could do a thousand tracks (laughs). Still, we set off on a program which had me record non-stop, for a year, what you could call stock music – though it also allowed me to produce other, more ambitious records.

Did you know the other library music composers?

Yes. There was a dozen of them on that market, but they were the good ones. Jacky Giordano was a great friend and we worked together – he died unfortunately. He was very productive, a talented musician, and open-minded. But he got involved in this thing, some shady business with the social insurance. That ate him up, even though he was an outstanding pianist and composer. We did Schifters together, among other things. It was mostly written improvisations: you’d make a score with just a theme, a framework of chords onto which musicians could improvise…

You were working for an incredible amount of labels…

Yes. I only ever signed a contract with Barclay. I didn’t want to. The labels would release records and I’d collect the rights via the SACEM, which was fine by me since most of the records worked well, we’d hear them on the radio and on the television, that was the editors’ work. At Montparnasse 2000 for example, the boss had relations in nightlife – he’d meet up with them in his club and give out his records.

Was it profitable, for you?

Making music for the Sacrée Soirée or the Shadoks obviously pays well.

What’s surprising is the variety of your inspiration: jazz rock, psych, funk, some tracks which are near-experimental… where does that eclecticism come from?

Most likely from composing movie soundtracks, because in that field you need to be able to do everything. I became the “jack of all trades” (laughs). It’s one of the great joys of music.

The advent of disco seemingly changed your career – how did you discover the genre?

I was one of the first disco composers in France. I was in the studio with some musicians who said they had “a client looking for someone who makes feisty music just like you.” I met the guy in question who told me: “there’s something coming, if you can make some I’d be interested. It’s called disco…” I was really into funk music, so I went for it and that gave M.B.T. Soul – the title track “The Chase” is 16 or 17 minutes long. It was released on Polygram. Cerrone was on the same label, and released a record one week before I did. We sold 100000 copies, were on the Canadian billboard… You remember “Love in C minor”, by Cerrone? It’s the same thing as “Chase”, and yet we didn’t even copy each other. That was the disco style… Success is often due to chance and determination.

You also made synthetic music with a spatial tendency…

Yes, To The Land Of No Return, with and ARP. I was very much in the know about new instruments coming out, though it wasn’t so much the instruments that inspired me; rather, I’d have an idea and look for sounds and thus instruments which would match that idea.

How did the three symphonic pieces you made for the radio come about?

I had made the score for a ballet with a writer called Gérard Mourgue. He’s the one who sent me to Radio France to present a project, which they accepted. That’s how I ended up directing an orchestra of 40 musicians. Gérard Mourgue was a poet and I had selected some of his writings on an album I made, Les Grands Poètes, on which there are also previously unpublished poems by Jacques Prévert and Aragon.

And you recorded music for erotic movies…

Yes with the director Gérard Kikoïne, a pioneer of the genre. I did the score for l’Amour à la bouche and then for two American movies. But movie soundtracks were too complicated.

Some of the themes for l’Amour à la bouche appear on a strange record: Hotel Montparnasse Park…

Yes, I had gone to meet the boss of this hotel and proposed to make a record about it. We made 1000 for 12000 francs, it was well paid. Then I went for the Concorde La Fayette.

You never wanted to be part of a band?

No, it wasn’t my thing. I was part of orchestras, it’s a different kind of investment. To be part of a band you’d have to do that and only that. It didn’t fit with my nature. The same way I didn’t want to dedicate myself to one style only.

Did you listen to New-age music before releasing your relaxation albums for Nature et Découverte?

I created my style with these albums, which were a big hit. New-age music is melody-less, while what I propose is based on melodies. That’s the whole difference. The Nature record released in 94 was the first relaxation record. I had met a musician who played the pan pipes and I thought “hey, that’s nice” (laughs), so I made a disco rhythmic with pan pipes. This one guy had a listen and said: “it’s great, just remove the rhythmic”, (laughs) “and that’ll make an album.” So I reworked it all from the basis. Behind the flatness it’s still punchy, we just don’t hear it anymore. The result was 120000 copies sold in four years. And I can tell you there’s still room and ideas for more.