(ENGLISH TEXT BELOW)

“Oh femme, femme africaine

Oh femme, femme béninoise

Femme noir, lève toi, ne dort pas

Oh femme noir, lève toi ne dort pas

Tu peu devenir, président de la république

Tu peu devenir, premier ministre du pays

Lève-toi, il faut faire, quelque chose

Femme africaine, soit indépendante

Le pays a besoin de nous, allons à l’école

L’Afrique a besoin de toi, il faut travailler

Le monde a besoin de nous, levons nous allons défendre

Femme africaine, soit indépendante »

Star Feminine Band “Femme Africaine”

Sans crier gare, une formation de jeunes filles originaires d’une région reculée du Bénin, bouscule l’idiome rock garage avec une fraîcheur, une inventivité et une énergie stupéfiantes, jouant juste, haut et fort.

Au cours de la première partie du vingtième siècle, le découpage de la majorité de l’Afrique par les puissances européennes introduit une modernité forcée un peu partout sur le continent. Dans les villes et les ports, le continent bruisse d’une agitation nouvelle alors que l’électricité commence sa timide apparition. A la faveur de transports maritimes en plein essor, les 78 tours ramenés par les marins latino-américains, en particulier cubains, mais aussi par les soldats ou les colons européens, influencent durablement de nouvelles orientations musicales le long des côtes africaines.

On assiste ainsi progressivement à une réinterprétation de ces musiques cubaines, mais aussi caribéennes, jazz ou rhythm’n’blues. Originaires en grande partie d’Afrique, ces musiques revenues des Amériques font office de vérité naturelle sur le continent. Certains orchestres décident ainsi de « réafricaniser » ces musiques afro-cubaines et noires américaines écoutées sur dans les ports, sur la place publique ou diffusées sur les ondes. Les bars et dancings, ainsi que les associations de jeunesse jouent également un rôle important dans la diffusion et le développement de ces musiques.

A l’image de ce qui se passe dans la plupart des villes d’Afrique, de nombreux orchestres voient le jour au cours des années 1950 et 1960. Ils incarnent des symboles de modernité, au même titre que l’électricité, les automobiles et le cinéma. L’euphorie des années qui suivent l’indépendance est donc mise en musique par ces orchestres. Ceux-ci sont en partie influencés par les formations de danse ghanéennes qui sillonnent alors toutes les grandes villes du Golfe du Bénin, du Nigeria jusqu’au Liberia. Les échanges culturels sont fertiles.

Au début des années 1960, les riches traditions locales du Bénin, à commencer par les musiques de transe et de cérémonie vaudou commencent à fusionner avec l’afro-cubain, la rumba congolaise et le high-life. Des dizaines d’orchestres, d’artistes et de labels participent à ce mouvement sans précédent. Par rapport à sa population, le Bénin est le pays d’Afrique le plus prolifique en terme de production discographique, notamment au cours d’une effervescence extraordinaire durant les années 1970.

A la manière de ce qu’il se passe alors en Guinée, en Côte d’Ivoire ou au Mali, chaque grande ville ou préfecture possède au moins un orchestre moderne, que ce soit à Cotonou, Porto-Novo, Parakou, Ouidah, Natitingou, Abomey ou Bohicon. Des formations comme les Black Santiagos, le National Jazz du Dahomey, le Super Star de Ouidah, le Picoby Band et le Renova Band d’Abomey ou encore les Black Dragons de Porto Novo se font une réputation au niveau national. Au milieu des années 1960, la chanteuse Sophie Edia devient la première voix féminine à diffuser la musique béninoise en dehors des frontières du pays, à commencer par le Nigeria.

En 1975, l’Unesco promeut l’Année Internationale de la Femme, un événement destiné à faire prendre conscience du rôle des femmes dans de nombreux pays, là où leur rôle est trop souvent minimisé ou bafoué. Cette initiative a un impact considérable sur le continent africain. Que ce soit au Mali avec Fanta Damba, en Côte d’Ivoire avec Mamadou Doumbia, au Cameroun avec Anne-Marie Nzie, au Congo Brazzaville avec Les Bantous de la Capitale ou au Burkina Faso avec Echo del Africa, tous rendent hommage à cette initiative. Partout en Afrique francophone, les consciences s’éveillent quand aux droits des femmes.

En 1976, le poète camerounais Francis Bebey publie l’éloquent La Condition Masculine. Sous ses airs humoristiques, cette merveille interpelle elle aussi les consciences, sans pour autant sombrer dans une moralisation outrancière.

“Tu ne connais pas Sizana

Sizana, c’est ma femme

C’est ma femme puisque nous sommes mariés depuis plus de dix-sept ans maintenant

Elle était très gentille auparavant

Je lui disais “Sizana, donne-moi de l’eau”

Et elle m’apportait de l’eau à boire

De l’eau claire, hein, très bonne!

Je luis disais, “Sizana, fais-ceci”

“Fais-cela” et elle obéissait

Et moi j’étais content, je regardais tout ça avec bonheur

Ah, je te dis que Sizana, Sizana, elle était une très bonne épouse auparavant

Seulement, depuis quelques jours, les gens, là

Ils ont apporté ici la condition féminine

Il paraît que là-bas, chez eux, ils ont installé une femme dans un bureau

Pour qu’elle donne des ordres aux hommes

Aïe, tu m’entends des choses pareilles?”

Francis Bebey “La condition masculine”

Son compatriote Ali Baba creuse le même sillon avec La Condition Féminine, on ne tape pas la femme. En Côte d’Ivoire, Sidiki Bakaba déclame un poème de Léopold Sédar Senghor sur l’éloquent 45 tours Femme noire, mis en musique en mode spiritual jazz. Au Bénin, en 1977, le batteur Danialou Sagbohan enregistre l’éloquent Viva, femme africaine, un single fondateur pour la prise de conscience féminine dans ce pays.

L’enthousiasme de ces années d’émancipation retombe toutefois au cours des années 1980, avec son lot d’unions imposées, de grossesses précoces, de violences diverses et d’excisions, notamment en Afrique sahélienne. En 1989, Oumou Sangaré, une jeune chanteuse malienne originaire du Wassoulou, enregistre l’historique Moussoulou (« Femmes »), aux sonorités claires et acoustiques. Puissant et percutant, son chant influence de nombreuses chanteuses du continent au cours des décennies suivantes. Ce premier opus offre un instantané saisissant de la condition des femmes d’Afrique de l’Ouest à la fin des années 1980. A ses débuts, elle chante dans les rues de Bamako, pour gagner de quoi manger.

Oumou Sangaré modernise radicalement la tradition des cantatrices locales. Elle séduit immédiatement grâce à sa voix féline, mais aussi en raison de ses textes qui dénoncent la polygamie, les mariages forcés ou l’excision, prônant une sensualité, une fierté et une féminité sans ambages. Son succès est immédiat, avec des millions de cassettes vendues dans tous les marchés d’Afrique de l’Ouest. Oumou Sangaré accède au statut de superstar de la pop africaine.

Femme malienne inscrite dans son époque, elle incarne le triomphe de l’amour et des émotions féminines en toutes circonstances. Si la musique sur laquelle elle chante est séduisante, audacieuse et pleine de vie, ses paroles imposent une nouvelle manière de voir. Celles-ci sont plus importantes que la musique. Elle est inspirée par les évènements sociaux et par son environnement immédiat. Femme libre, elle dit ce qu’elle veut et ce qu’elle pense. Sa musique, apolitique mais féministe, a un large impact. Son message à propos de la femme africaine rencontre un très large écho, sur le continent comme dans le reste du monde.

Au cours des années 1990, la béninoise Angélique Kidjo s’impose également comme l’une des grandes voix féminines africaines. Elle porte haut l’héritage musical béninois. Née en 1960 à Ouidah, le berceau du vaudouisme, elle est bercée enfant par le théâtre et les sonorités afro-américaines. Encore adolescente, elle se fait un nom dans tout le pays grâce à ses apparitions radiophoniques. A ses débuts, elle est accompagnée par le Poly Rythmo de Cotonou, formé en 1969. Cet orchestre est le plus légendaire du pays, au gré d’une discographie pléthorique, de centaines de singles, d’albums et d’innombrables tournées partout dans le monde.

En 1980, Angélique Kidjo enregistre son premier album Pretty à Paris sous la houlette du Camerounais Ekambi Brillant. Son succès en Afrique de l’Ouest est immédiat. Elle s’installe en France en 1983, en pleine explosion des musiques venues d’Afrique. Elle participe à divers groupes, avant de se lancer en solo et de s’imposer comme la grande voix féminine du Bénin. Quarante ans plus tard, ses héritières et compatriotes sont en passe de rayonner au grand jour.

Dernière grande ville étape sur la route nationale qui sillonne le Nord Ouest du Bénin, la paisible Natitingou s’étale en longueur de part et d’autre d’un ruban d’asphalte. Après une quinzaine d’heures de route depuis la capitale économique Cotonou, cette ville offre une étape appréciable avant de poursuivre vers le Burkina Faso, le Togo ou l’immense réserve de la Pendjari, via Tanguiéta, là où commencent les vastes plaines sahéliennes et se réfugient les derniers grands animaux sauvages ayant échappé à la folie des hommes.

Ville de croisement dans cette région située au carrefour de quatre pays, Natitingou contrôle l’accès de la région des collines de l’Atakora, qui ceignent la ville. Enclavée, la commune de Natitingou est largement isolée du reste du Bénin, tributaire du ravitaillement routier, des coupures d’électricité et des éléments naturels, parfois hostiles.

Longtemps rétive à toute forme de domination, cette région a pour héros Kaba. Au début de la première guerre mondiale, il refusa la conscription militaire obligatoire et mena une guérilla farouche contre l’oppression coloniale. Cette guerre perdue se termina dans un bain de sang en 1917. A la sortie de la ville, le musée Kaba raconte cette résistance du peuple somba, notamment par son évocation de sa culture, de ses cérémonies, du travail du fer ou encore des cases circulaires, au toit conique, souvent surélevées et fortifiées, appelées tatas que l’on retrouve dans une bonne partie du Sahel.

Kaba donna son nom à l’un des premiers orchestres de Natitingou, Kaba Diya, actif entre 1979 et 1983. Celui-ci publia un unique album de musiques modernes en 1980, représentatif de la culture de cette région, à commencer par sa pochette. Si Kaba Diya a eu l’occasion de publier un 33 tours, d’autres formations locales ont également marqué les esprits. Formation historique créée dès 1960, l’orchestre Bopeci a publié deux 45 tours. En revanche, Nati Fiesta, le Tchankpa Jazz ou L’Echo de l’Atakora n’ont a priori jamais publié leurs morceaux au format vinyle. Plus récemment, depuis le milieu des années 1990, Gay Stone, Cool Star, Ata Echo, les 3 Couleurs, le groupe Tchingas, Zénith Temple, Excelsior mais aussi depuis 2017 la formation FMG animent les nuits de Natitingou et de l’Atakora.

Culturellement et musicalement, cette région du Nord-Ouest du Bénin est plus proche de l’aire d’influence sahélienne que de celle du Sud du pays, du sato, du vaudou et du folklore modernisé développé par des formations comme l’orchestre Black Santiagos qui donna ainsi naissance à l’afrobeat dès le milieu des années 1960, avant d’être repris et développé par Fela Kuti.

C’est dans cette région de contraste, de paysages à la fois verts et rocailleux qu’ont grandies les sept vedettes juvéniles du Star Feminine Band. Souvent déscolarisées et promises à vendre des arachides, des bananes, du gari ou du tchoucoutou, une boisson locale à base de mil au bord du goudron, la plupart des jeunes filles de la région n’ont guère d’avenir. Les mariages forcés et les grossesses précoces sont légion.

Conscient de cette précarité, le musicien André Baleguemon décide de former un groupe exclusivement féminin ancré dans les préoccupations de son époque. Il laisse la part belle à la guitare, à la batterie et au clavier, instruments admirés depuis son enfance, symboles de modernité dans cette région reculée. Son constat est simple : « Dans le Nord, les filles n’évoluent pas beaucoup et les femmes sont mises de côté. J’ai simplement voulu montrer la valeur de la femme dans les sociétés du Nord Bénin en formant un orchestre féminin ».

Originaire de Tchaourou, une vaste commune située au centre Est du Bénin, André Balaguemon se passionne très jeune pour la musique. Il intègre l’orchestre Sam 11 de Parakou, au Nord Est du pays, au cours des années 1990, où il est successivement trompettiste puis guitariste. En 1999, il descend à Cotonou avant de se fixer dans le Nord-Ouest du pays, afin de renouer avec ses racines et ses passions musicales.

Le 25 juillet 2016, avec le soutien de la municipalité de Natitingou, André lance un communiqué sur les ondes de Nanto FM afin de former des filles bénévolement à la musique. Quelques jours plus tard, des dizaines d’aspirantes musiciennes se présentent à la Maison des Jeunes. « Les filles qui sont venues ne connaissaient rien à la musique. Les sept sélectionnées sont de jeunes filles d’ethnie waama et nabo. Venues des villages alentour, certaines n’avaient même jamais vu ce genre d’instruments ».

Depuis l’époque des indépendances, posséder ses propres instruments a toujours été l’une des conditions premières pour tout orchestre africain qui se respecte. Avec les instruments achetés par ses soins, batterie, deux guitares et des claviers, ajoutés à quelques percussions, André effectue ses premiers essais musicaux avec ses nouvelles recrues, une poignée de jeunes filles parmi les plus motivées.

Rapidement, les filles se passionnent pour leurs nouvelles activités musicales, apprenant la batterie, la guitare, les harmonies vocales, le piano. Leurs progrès sont stupéfiants. Un intense travail de formation musicale se met en place, à commencer par des ateliers de batterie, l’instrument fétiche de la formation. Angélique et Urrice sont à la batterie et au chant, secondées par Marguerite, la troisième batteuse. Sandrine est aux claviers, tout comme Grace, qui œuvre également au chant. Julienne est à la basse et Anne à la guitare.

Comme influence fondatrice de leur démarche, André cite volontiers Angélique Kidjo, « notre inspiration principale. C’est une femme que l’on ne peut pas ignorer. Miriam Makeba est aussi une source de fierté, comme Sagbohan Danialou, Stanislas Tohon. Kaba Diya, le grand orchestre régional nous a aussi beaucoup inspiré ».

La pugnacité d’André est l’un des éléments clé de cette réussite humaine et artistique. Les filles ont déjà donné des dizaines de concerts dans la région, forgeant et étoffant un répertoire déjà solide, tout en séduisant un public local toujours plus nombreux. Outre les progrès musicaux, il s’implique personnellement auprès de chaque famille pour leur faire comprendre l’importance de son projet, à la fois sur le plan musical et humain, notamment sur le fait que chaque fille reste scolarisée et ne soit pas entrainée dans un mariage forcé.

Dans l’histoire des musiques populaires africaines, peu nombreuses sont les formations féminines. Si les Amazones de Guinée, la Famille Bassavé et les Colombes de la Révolution au Burkina, les Sœurs Comoë en Côte d’Ivoire ou les Lijadu Sisters au Nigeria viennent notamment à l’esprit, Star Feminine Band n’a certainement pas d’équivalent au Bénin. La fraicheur, l’insouciance et la liberté, mais surtout le talent de ces jeunes filles est sans appel.

A la fin de l’année 2018, la rencontre avec le jeune ingénieur français Jérémie Verdier accélère le cours des choses. En mission dans la région, il fait appel à ses amis espagnols Juan Toran et Juan Serra. Ceux-ci débarquent avec leur matériel d’enregistrement afin de graver les premiers morceaux de la jeune formation dans l’annexe du Musée local. Au hasard des rencontres et mû par un instinct sûr, Jean-Baptiste Guillot entend ces bandes. Il décide alors de partir à leur rencontre à la fin de l’année 2019. Ce voyage mémorable de quelques jours scelle le destin de l’album que vous tenez entre vos mains.

Aujourd’hui âgées de neuf à quinze ans, les sept jeunes filles du Star Feminine Band continuent d’aller à l’école. Dans une annexe du Musée Départemental de Natitingou, André a installé le local de répétition de la formation. Plusieurs fois par semaine, les sept jeunes filles se retrouvent dans cet endroit, habitées par les plus nobles aspirations, celles de chanter leur culture, leur condition féminine et leur possible émancipation. Leurs répétitions ont lieu trois fois par semaine, de 16h à 19h. En période de vacances scolaires, elles répètent tous les jours du lundi au vendredi de 9h à 17h.

En 2020, dans nombre de zones rurales du continent africain, mais aussi parfois dans les grandes métropoles, la situation des femmes n’a guère évolué depuis les années 1960, l’époque des indépendances où l’on pensait que tout aller changer à travers un continent en quête de modernité, de culture et d’émancipation. S’il a fait des émules en Afrique, le mouvement Me Too n’a guère touché les parties les plus reculées du continent.

Prenant son essor, le Star Feminine Band donne plusieurs concerts à Natitingou mais aussi dans les villages alentour. A chaque fois qu’elles jouent en public, elles rassemblent un public local toujours plus nombreux et curieux quand à la démarche de cette formation iconoclaste. Les femmes viennent en masse, mais plus généralement les parents avec leurs enfants, mais aussi beaucoup de personnes âgées, dans une région où les activités culturelles se limitent souvent aux cérémonies agraires ou funéraires.

André Baleguemon et ses talentueuses protégées adaptent des chansons d’inspiration traditionnelle, dans une veine de folklore modernisé. « Nous jouons les danses de rythme waama, nous voulons les mettre à l’honneur. Nous avons composé des chansons en français, en waama et ditamari, deux ethnies méconnues du Nord. Nous chantons aussi des morceaux en langue bariba, ainsi qu’en langue fon, langue majoritaire au Bénin, dans le nouveau répertoire, afin de se faire comprendre du plus grand nombre ».

Peba est chanté en waama. Il y est dit que les filles vont à l’école pour être elles mêmes. Chantées en français les paroles de La musique et de Femme africaine sont éloquentes quant aux messages énoncés. Timtilu est chantée en ditamari. Les filles conseillent ici de ne pas délaisser leur culture, mais plutôt de la mettre à l’honneur. Chant d’émancipation en langue peule, Rew Be Me Light, est une ode à la femme, un encouragement pour réussir sa propre carrière et réussir en tant que femme.

Fédérateur, Iseo est chanté en bariba. « Hommes et femmes, levons nous, du sud, du centre, du nord, unissons-nous et soyons un pour que le pays évolue ». Il s’agit ici de rassembler les régions et la diversité des cultures du Bénin. Louange à Dieu en peul, Montealla est d’inspiration mandingue dans son interprétation. Chanté en bariba, Idesouse indique que les filles doivent être scolarisées et aller au bout de leurs études pour défendre les valeurs de la femme. Elles doivent se battre d’autant plus afin de gagner cette reconnaissance.

Au gré de chacun ces morceaux, chacune des filles de Star Feminine Band apporte sa propre inspiration. André compose tous leurs morceaux. Comme il le concède : « Elles amènent leurs idées. Le rêve de ces filles c’est de devenir des stars au niveau international. Elles doivent montrer la valeur de la femme dans le monde entier. Parler de l’Afrique, accomplir de grandes missions autour des valeurs de la femme. Elles parlent de l’excision, de la maltraitance et des violences faites aux filles. Nous voulons inscrire ces sujets dans le débat politique au Bénin, puis ailleurs en Afrique si cela nous est un jour possible ».

Avec beaucoup d’aplomb, un œcuménisme et un charisme indéniables, Star Feminine Band s’impose aujourd’hui comme l’une des fiertés de la région de l’Atakora. Le groupe commence même à susciter des vocations, tout en semant les graines pour la prochaine génération de jeunes filles provinciales, mues par une volonté de fer, forgée du même minerai que les armes de Kaba, héros oublié de l’Atakora.

Véritables héroïnes du quotidien, les sept filles du Star Feminine Band incarne le futur et la relève d’une génération en quête de reconnaissance. « Dans les années 1960, Dieu était une jeune fille noire qui chantait » avait coutume de dire le duo de compositeur new-yorkais Carole King et Gerry Coffin. Soixante années plus tard, dans une des provinces oubliées du continent africain, cet adage revêt toute sa valeur.

Florent Mazzoleni

////////////////////ENGLISH///////////////////////////////

“Oh woman, African woman

Oh woman, Beninese woman

Black woman, get up, don’t sleep

Oh black woman, get up don’t sleep

You can become president of the republic

You can become the country’s Prime Minister

Get up, something has to be done

African woman, be independent

The country needs us, let’s go to school

Africa needs you, you have to work

The world needs us, stand up, let’s stand up

African woman, be independent”

Star Feminine Band “Femme Africaine”

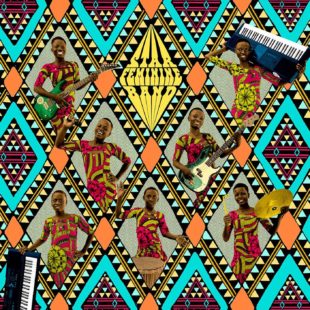

Without warning, a group of young girls from a remote region of Benin is shaking up the world of garage rock with breathtaking freshness, ingenuity and energy, playing spot-on, loud and clear.

During the first half of the twentieth century, the division of the majority of Africa by European powers introduced a forced modernity throughout most of the continent. In cities and ports, the continent buzzed with new energy as electricity began its timid appearance. Thanks to booming maritime transport, the 78 rpm records brought in by Latin American sailors, in particular Cubans, but also by European soldiers or settlers, had a durable influence on the new musical interests along the African coasts.

Gradually, the reinterpretation of Cuban, but also Caribbean, jazz or rhythm’n’ blues music began. For the most part originally from Africa, this music from the Americas acted as a natural truth on the continent. Some orchestras thus decided to “re-Africanize” this Afro-Cuban and black American music heard in ports, public places or broadcasted on the radio. Bars and dance halls, as well as youth associations also played an important role in the dissemination and development of this music.

In most African cities, many orchestras were born during the 1950s and 1960s. They became symbols of modernity, like electricity, cars and cinema. The euphoria of the years following independence was therefore set to music by these orchestras. These were partly influenced by Ghanaian dance formations that toured through all the major cities of the Gulf of Benin, from Nigeria to Liberia. The cultural exchanges were fertile.

In the early 1960s, the rich local traditions of Benin, starting with trance and voodoo ceremonial music, began to merge with Afro-Cuban, Congolese rumba and high-life. Dozens of orchestras, artists and labels participated in this unprecedented movement. Unlike its population count, Benin is the most prolific African country in terms of record production, especially during the extraordinary exhilaration of the 1970s.

In Guinea, Ivory Coast or Mali, each major city or prefecture had at least one modern orchestra, whether in Cotonou, Porto-Novo, Parakou, Ouidah, Natitingou, Abomey or Bohicon. Bands such as the Black Santiagos, the National Jazz of Dahomey, the Super Star of Ouidah, the Picoby Band, the Renova Band of Abomey and the Black Dragons of Porto Novo gained in popularity at the national level. In the mid-1960s, singer Sophie Edia became the first female singer to distribute Beninese music outside of the country’s borders, starting with Nigeria.

In 1975, Unesco promoted the International Women’s Year, an event designed to raise awareness of the role of women in many countries, where their role is too often downplayed or flouted. This initiative had a considerable impact on the African continent. Whether in Mali with Fanta Damba, in Côte d’Ivoire with Mamadou Doumbia, in Cameroon with Anne-Marie Nzie, in Congo Brazzaville with Les Bantous de la Capitale or in Burkina Faso with Echo del Africa, they all paid tribute to this initiative. All over French-speaking Africa, people were awakening to women’s rights.

In 1976, the Cameroonian poet Francis Bebey published the eloquent La Condition Masculine. Under its humorous airs, this gem challenged morals with lightness and tact.

“You don’t know Sizana

Sizana is my wife

She’s my wife since we’ve been married for over seventeen years now

She used to be very nice

I would say to her “Sizana, give me water”

And she would bring me water to drink

Clear water, huh, very good!

I would say, “Sizana, do this”

“Do that” and she would obey

And I was happy

Ah, I tell you that Sizana, Sizana, she used to be a very good wife

But, these past few days, these people

They brought the female condition here

Apparently over there, where they live, they put a woman in an office

So that she can give orders to men

Ouch, have you ever heard such a thing? “

Francis Bebey “La condition masculine”

His fellow countryman Ali Baba ploughed the same furrow with La Condition Féminine, on ne tape pas la femme (The Feminine Condition, you don’t hit a woman). In Ivory Coast, Sidiki Bakaba recited a poem by Léopold Sédar Senghor on the eloquent Femme noir (Black Woman) 45 rpm, set to spiritual jazz. In Benin, in 1977, drummer Danialou Sagbohan recorded the eloquent Viva, femme africaine (Viva, African woman), a founding song for women’s rights in his country.

However, the enthusiasm of these years of emancipation dropped during the 1980s, with its share of forced unions, early pregnancies, various forms of violence and female genital mutilation, particularly in Sahelian Africa. In 1989, Oumou Sangaré, a young Malian singer from Wassoulou, recorded the historic Moussoulou (“Women”), with clear and acoustic tones. Powerful and impactful, her song influenced many female singers on the continent during the following decades. This first opus offered a striking snapshot of the condition of West African women in the late 1980s. When she started out, she sang in the streets of Bamako in order to earn enough to eat.

Oumou Sangaré radically modernized the tradition of local singers. She immediately seduces the listener with her feline voice, but also with her lyrics which denounce polygamy, forced marriages or female genital mutilation, advocating sensuality, pride and unambiguous femininity. Her success was immediate, with millions of cassettes sold throughout all West African markets. Oumou Sangaré reached the status of African popstar.

A Malian woman of her time, she embodied the triumph of love and female emotions in all circumstances. If the music on which she sings is attractive, daring and full of life, her words impose a new way of seeing things. These words weighed more than the music. Inspired by social events and her immediate environment, a free woman, she spoke her truth. Her music, apolitical but feminist, had a wide impact. Her message about African women was widely heard, both on the continent and throughout the rest of the world.

During the 1990s, the Beninese Angélique Kidjo also established herself as one of the great African female singers. She proudly promoted Beninese musical heritage. Born in 1960 in Ouidah, the cradle of voodooism, she was raised in the world of theater and African-American sounds. As a teenager, she made a name for herself throughout the country thanks to her radio appearances. At the start of her career, she was accompanied by the Poly Rythmo of Cotonou, formed in 1969. The most legendary orchestra of the country, according to an enormous discography that includes hundreds of singles, albums as well as countless tours around the world.

In 1980, Angélique Kidjo recorded her first album Pretty in Paris under the leadership of the Cameroonian Ekambi Brillant. Its success in West Africa was immediate. She moved to France in 1983 when music from Africa was all the hype. She joined different bands, before going solo and establishing herself as the greatest female voice of Benin. Forty years later, her successors and compatriots are about to shine bright.

The last big city on the main road that criss-crosses northwestern Benin, peaceful Natitingou stretches out on either side of a strip of asphalt. After a fifteen hour drive from the business capital of Cotonou, this city offers a valuable stopover before heading to Burkina Faso, Togo or the huge Pendjari reserve, via Tanguiéta, where the vast Sahelian plains begin and where the last great wild animals to have escaped the madness of mankind take refuge.

One of the region’s main crossover cities located at the crossroads of four countries, Natitingou controls the access to the Atakora hills region, which surrounds the city. Landlocked, the city of Natitingou is largely isolated from the rest of Benin, dependent on road deliveries and subject to power cuts and sometimes hostile natural elements.

Steadily reluctant to any form of domination, this region’s hero is named Kaba. At the start of the First World War, he refused compulsory military service and led a fierce guerrilla war against colonial oppression. This lost war ended in a bloodbath in 1917. Upon leaving the city, the Kaba museum tells the story of the resistance of the Somba people, in particular through its evocation of its culture, its ceremonies, its iron work and even its circular huts with conical roofs, often raised and fortified, called tatas that are found in a good part of the Sahel.

Kaba gave his name to one of Natitingou’s first orchestras, Kaba Diya. Active between 1979 and 1983, it released a unique record of modern music in 1980, representative of the culture of its region, starting with the artwork. If Kaba Diya had the opportunity of releasing an LP, so did other local bands. A historical group formed in 1960, the Bopeci orchestra, released two 45 rpm records. On the other hand, Nati Fiesta, Tchankpa Jazz or L’Echo de l’Atakora never had a chance to release their songs on vinyl. More recently, since the mid 90s, Gay Stone, Cool Star, Ata Echo, Les 3 Couleurs, the Tchingas band, Zénith Temple, Excelsior and also since 2017 the FMG formation have been livening up the nights of Natitingou and Atakora.

Culturally and musically, this region of North-West Benin is more influenced by the Sahel than by the South of the country, by sato, voodoo and modernized folklore developed by groups like the Black Santiagos orchestra which gave birth to Afrobeat in the mid-1960s, before being adopted and developed by Fela Kuti.

It is in this region full of contrast, of both green and rocky landscapes, that the seven young stars of the Star Feminine Band grew up. Often taken out of school and sent to sell peanuts, bananas, gari or tchoucoutou, a local millet drink on the side of the road, most young girls in the region have little future to look forward to. Forced marriages and early pregnancies in the majority of cases.

Aware of this insecurity, a musician named André Baleguemon decided to form an exclusively female band rooted in the concerns of its time. He puts the spotlight on the guitar, drums and keyboard, instruments he has admired since his childhood, symbols of modernity in this remote region. His observation is simple: “In the North, girls have no room to advance and women are put aside. I simply wanted to show the importance of women in the societies of North Benin by forming a female orchestra “.

Originally from Tchaourou, a vast commune located in central eastern Benin, André Balaguemon developed a passion for music at a very young age. During the 1990s, he joined the Sam 11 orchestra in Parakou, in the northeastern part of the country, where he successively played trumpet and guitar. In 1999, he spent some time in Cotonou before settling in the northwest, in order to reconnect with his roots and musical passions.

On July 25th, 2016, with the support of the city of Natitingou, André launched a press release on Nanto FM offering to help train girls in music for free. A few days later, dozens of aspiring musicians showed up at the Youth Center. “The girls who came didn’t know anything about music. We selected seven girls of the Waama and Nabo ethnic groups from the surrounding villages, some had never even seen these types of instruments before. “

Since the independence era, having your own instruments has always been the prerequisite of any self-respected African orchestra. With drums, two guitars, keyboards and some added percussion purchased by André, the first musical tests began with his new recruits, a handful of young girls among the most motivated.

The girls quickly became passionate about their new musical activities, learning how to play drums, guitar, piano and sing vocal harmonies. Their progress was astounding. An intense work of musical training took place, starting with drum workshops, their favorite instrument. Angelique and Urrice on drums and vocals, assisted by Marguerite, the third drummer. Sandrine is on keyboards, as is Grace, who also sings vocals. Julienne is on bass and Anne on guitar.

As the founding influence of their approach, André readily quotes Angélique Kidjo, “our main inspiration. She is a woman you cannot ignore. Miriam Makeba is also a source of pride, as is Sagbohan Danialou, Stanislas Tohon. Kaba Diya, the great regional orchestra, also inspired us a lot. ”

André’s determination is one of the key elements of this human and artistic success. The girls have already performed dozens of concerts in the region, forging and expanding an already solid repertoire, while attracting an ever-increasing local audience. In addition to musical progress, he has been personally involved with each family, showing them the importance of his project, both musically and humanly and in particular the fact that each girl must remain in school and not be forced into marriage.

There are very few female bands in the history of popular African music. If the Amazones de Guinée, la Famille Bassavé and les Colombes de la Révolution in Burkina, the Sœurs Comoë in Ivory Coast or the Lijadu Sisters in Nigeria notably come to mind, Star Feminine Band has no equivalent in Benin. The originality, carefree attitude, freedom, and above all the talent of these young girls is undeniable.

At the end of 2018, their encounter with the young French sound engineer Jérémie Verdier accelerated the course of things. On a mission in the region, he called on his Spanish friends Juan Toran and Juan Serra who showed up with their recording equipment in order to record the band’s first songs in the annex of the local museum. Random encounters and fate led Jean-Baptiste Guillot to hear the tapes. He decided to go meet them at the end of 2019. This short but memorable journey sealed the fate of the record you are now holding in your hands.

Now aged nine to fifteen, the seven girls of the Star Feminine Band continue to go to school. André installed a rehearsal room in an annex of the Departmental Museum of Natitingou. Several times a week, the seven young girls get together, inhabited by the noblest aspirations, those of singing their culture, their feminine condition and their possible emancipation. They rehearse three times a week, from 4 to 7 p.m. During school holidays, they rehearse daily from Monday to Friday from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

It’s 2020 but the situation of women in many rural areas of the African continent and also sometimes in large metropolises, has hardly changed since the 1960s, the era of independence when it was believed that everything would change in this continent that was searching for modernity, culture and emancipation. Although there were some followers of the Me Too movement in Africa, it hardly touched the most remote parts of the continent.

The Star Feminine Band is taking off. Performing several concerts in Natitingou but also in the surrounding villages. Each time they play in public, they bring together an ever-increasing and curious local audience when it comes to this one of a kind training. Women come en masse, as well as parents with their children, but also many elderly people, in a region where cultural activities are often limited to agricultural or funeral ceremonies.

André Baleguemon and his talented protégés adapt songs of traditional inspiration, in a vein of modernized folklore. “We play waama rhythm dances, we want to honor them. We compose songs in French, waama and ditamari, two unknown ethnic groups from the North. We also sing songs in the Bariba language, as well as the Fon language, the main language in Benin, in the new repertoire, in order to be understood by as many people as possible.”

Peba is sung in waama. It’s about girls going to school in order to be themselves. Sung in French, the lyrics of La Musique and Femme africaine speak for themselves. Timtilu is sung in ditamari. In this song, the girls give the advice to not abandon your culture, but rather to honor it. A song of emancipation in the peul language, Rew Be Me Light, is an ode to women, an encouragement to succeed in your own career and succeed as a woman.

A unifying song, Iseo is sung in bariba. “Men and women, let us rise, from the south, from the center, from the north, let us unite and be one so that the country can evolve”. This song is about bringing together the regions and the diversity of cultures in Benin. Praise be to God in peul, Montealla’s interpretation was inspired by mandingo. Sung in bariba, Idesouse indicates that girls must go to school until the end of their studies in order to defend the values of women. They have to fight all the more in order to gain this recognition.

Through all of these songs, each of the Star Feminine Band members brings their own inspiration. André composes all their songs. He admits: “They bring their ideas. The dream of these girls is to become international stars. They must show the importance of women throughout the world. Speak of Africa, accomplish great missions around the values of women. They talk about female genital mutilation, abuse and violence against girls. We want to include these subjects in the political debate in Benin, then elsewhere in Africa if this is ever possible ”.

With much confidence, an undeniable ecumenism and charisma, Star Feminine Band is one of the prides of the Atakora region. The band is even starting to instigate vocations, while sowing the seeds for the next generation of provincial girls, driven by an iron will, forged of the same mineral as the weapons of Kaba, forgotten hero of the Atakora.

True heroines of everyday life, the seven girls of the Star Feminine Band embody the future and the next generation in search of recognition. “In the 1960s, God was a black girl who sang” used to say New York composer duo Carole King and Gerry Goffin. Sixty years later, in one of the forgotten provinces of the African continent, this adage takes on its full value.

/////////////////////////GERMAN/////////////////////////

Oh woman, African woman

Oh woman, Beninese woman

Black woman, get up, don’t sleep

Oh black woman, get up don’t sleep

You can become president of the republic

You can become the country’s Prime Minister

Get up, something has to be done

African woman, be independent

The country needs us, let’s go to school

Africa needs you, you have to work

The world needs us, stand up, let’s stand up

African woman, be independent”

Star Feminine Band “Femme Africaine”

Aus einer abgelegenen Region im Nordwesten von Benin kommt die siebenköpfige Star Feminine Band, eine Gruppe junger Mädchen im Alter zwischen neun und fünfzehn Jahren, die frech, unbeschwert und voller Energie Genres wie Garage-Rock, Pop und traditionelle Songs ihrer Heimat durcheinanderwirbeln.

Geboren wurde die Band 2016 als Idee des professionellen Musikers André Baleguemon. Er wollte eine ausschließlich weiblich besetzte Band zusammenstellen, die sich den aktuellen Themen der Zeit annahm. Im Zentrum sollten Gitarre, Schlagzeug und Keyboards stehen, weil er diese Instrumente seit seiner Kindheit im ländlichen Tchaourou als Zeichen von Moderne bewundert hatte. Der Grund für seine Initiative: „Im Norden haben Mädchen keine Möglichkeiten weiterzukommen und Frauen werden an den Rand gedrängt. Ich wollte einfach zeigen, wie wichtig Frauen in der Gesellschaft Nord-Benins sind, indem ich ein weibliches Orchester gründe.“

Gesagt, getan: Unterstützt von der 35.000 Einwohner zählenden Stadt Natitingou, die fünfzehn Stunden Fahrt vom Regierungssitz Cotonou entfernt liegt, veröffentlichte André eine Pressemitteilung beim Radiosender Nanto FM, in der er kostenfreie Musikstunden für Mädchen anbot. Dem Aufruf folgten Dutzende junger Musikerinnen. „Die Mädchen wussten nichts über Musik – wir entschieden uns für sieben Mädchen aus den umliegenden Dörfern mit Waama und Nabo-Hintergrund. Einige von ihnen hatten Instrumente wie Keyboards noch nie gesehen.“

André kaufte zwei Schlagzeuge, zwei Gitarren, Keyboards und Percussion und die ersten Proben mit den hochmotivierten neuen Rekrutinnen begannen. Die Band machte in den intensiven Workshops und Proben erstaunlich schnell große Fortschritte und es kristallisierte sich folgendes Line-Up heraus: Angelique und Urrice an Schlagzeug und Gesang, unterstützt von der dritten Schlagzeugerin Marguerite, Sandrine an Keyboards, wie auch Grace, die außerdem singt. Julienne ist am Bass und Anne an der Gitarre zu hören.

Die Band hat mittlerweile Dutzende Konzerte in der Region gespielt, ihr Repertoire immer weiter ausgebaut und viele Fans vor Ort gewonnen, darunter viele Frauen, Eltern mit ihren Kindern und Ältere, für die es ansonsten auf dem Land nur wenig kulturelle Ablenkung gibt. Neben den musikalischen Fortschritten legt André Baleguemon einen weiteren Schwerpunkt seiner Arbeit darauf, die Familien von der Wichtigkeit des Projekts auch in menschlicher Hinsicht zu überzeugen, und zu bewirken, dass die Mädchen weiter in die Schule gehen statt in Gelegenheitsjobs als Straßenverkäuferinnen oder in die Heirat gezwungen zu werden.

Es gibt in der Geschichte der populären Musik Afrikas viele große Künstlerinnen, aber nur wenige weibliche Bands, darunter die Amazones de Guinée, die Famille Bassavé und les Colombes de la Révolution in Burkina Faso, die Sœurs Comoë aus der Elfenbeinküste oder die Lijadu Sisters aus Nigeria. In Benin gab und gibt es nichts Vergleichbares in puncto Haltung, Freiheit, Originalität und vor allem Talent.

Haupteinflussquelle für die Band ist laut André die große Angélique Kidjo, die selbst aus dem Benin stammt: „Sie ist eine Frau, die man nicht ignorieren kann. Auch auf Miriam Makeba wie auch Sagbohan Danialou und Stanislas Tohon sind wir sehr stolz und Kaba Diya, das große Orchester aus der Gegend hat uns stark inspiriert.“ Das zwischen 1979 und 1983 aktive Orchester Kaba Diya hatte sich nach dem Helden der Region „Kaba“ benannt, der im Ersten Weltkrieg den Militärdienst verweigerte und danach einen bitteren Guerillakrieg gegen die französische Kolonialmacht führte.

In vielen ländlichen Regionen des afrikanischen Kontinents und auch in manchen Metropolen hat sich das Leben der Frauen seit den 1960er Jahren, als während der Unabhängigkeitskämpfe ein positiver Wandel zu Modernität, Kultur und Emanzipation angestrebt wurde, kaum verändert. Selbst die aktuelle MeToo-Bewegung hat bislang keinen spürbaren Wandel bewirkt. Die Star Feminine Band thematisiert die Lage der Frauen in ihren Texten, die in verschiedenen Sprachen verfasst sind. André Baleguemon dazu: „wir komponieren Songs in Französisch, Waama und Ditamari, zwei unbekannte ethnische Gruppen aus dem Norden. Wir singen in unserem neuen Repertoire auch Songs in Bariba und Fon, der Hauptsprache in Benin, um von möglichst vielen Menschen verstanden zu werden.“

André komponiert die Songs, aber alle sieben Bandmitglieder bringen ihre eigenen Ideen mit ein, wie er sagt: „Sie sprechen über die weibliche Genitalverstümmelung, Missbrauch und Gewalt gegen Frauen. Wir wollen diese Themen in die politische Debatte in Benin und wenn möglich, auch anderswo in Afrika einschließen.“ Der Song „Peba“ ist in der Sprache Waama geschrieben und handelt von Mädchen, die zur Schule gehen, um sie selbst sein zu können; in „Femme Africaine“ geht es auf Französisch gesungen um Selbstbestimmung und Freiheit. „Timtilu“ in der Ditamari-Sprache animiert dazu, die eigene Kultur zu ehren und nicht aufzugeben; „Rew Be Me“ in der Peul-Sprache, ist eine Ode an die Frau, ein Song über die Emanzipation und eine Bestärkung, den eigenen Weg zu gehen. Das in Bariba gesungene Stück „Iseo“ will die Menschen aus unterschiedlichen Regionen und Kulturen vereinen, um sie voranzubringen und „Idesouse“ spornt Mädchen dazu an, ihre Schulzeit nicht zu früh zu beenden.

Ende 2018 brachte ein Treffen mit dem jungen französischen Toningenieur Jérémie Verdier das Projekt in Bewegung. Er holte seine spanischen Freunde Juan Toran und Juan Serra mit ihrem Aufnahmegerät an Bord, um die ersten Songs im Anbau eines Museums in Natitingou einzuspielen. Rein zufällig hörte Jean-Baptiste Guillot vom Label Born Bad Records die Aufnahmen und beschloss, die Band Ende 2019 in ihrer Heimat zu treffen. Daraus entwickelte sich die jetzt anstehende Albumveröffentlichung.

Mit einer gehörigen Portion Selbstvertrauen, viel Charisma und nicht zuletzt einem tiefen Glauben hat sich die Star Feminine Band zum Stolz der Atakora-Region entwickelt. Die Bandmitglieder verkörpern die Zukunft. Sie schauen sich nach Ausbildungsberufen um und bereiten damit den Boden für die nächste Generation der Mädchen aus der Provinz. Gerry Goffins berühmte Aussage „In the Sixties, God was a young black girl who could sing” nimmt sechzig Jahre später in einer vergessenen Provinz des afrikanischen Kontinents neue Bedeutung an.

Florent Mazolleni